How can I describe Bukowski’s poetry? Let’s start off with this quote from Sounes’ book:

The best of Bukowski’s mature poetry was written in [a] minimalistic style, although it’s not to everyone’s taste. ‘Bukowski’s poetry was essentially stories, just like prose,’ says Lawrence Ferlinghetti. ‘It just happened some days that he didn’t get the carriage of the typewriter to the end of the line. Depends how badly hungover he was when he started to type.’

He has a point up to a point. I suspect he’s being not a little flippant here too. The thing I’ve learned about Bukowski is that one shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. He may well have looked like a hobo but that didn’t make him one and even if he was one then who says that unwashed equates with unread? I’m reminded of one of the most famous tramps in theatre:

VLADIMIR:

You should have been a poet.

ESTRAGON:

I was. (Gesture towards his rags.) Isn't that obvious?

Silence.

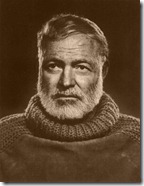

but to me, the twenties centred mostly on Hemingway

coming out of the war and beginning to type

it was all so simple, all so deliciously clear

from ‘the last generation’

and he appreciated the poetry of Pablo Neruda and Robinson Jeffers:

I also carried the Cantos

in and out

and Ezra helped me

strengthen my arms if not

my brain.

from ‘the burning of the dream’ (about the burning of the L. A. Public Library)

His approach to writing – both poetry and prose – was similarly straightforward– ‘one simple line after another’ – and this ensures that his writing has immediacy about it. You don’t need to think about, it hits you straight in the face. That doesn’t mean you can’t think about it because let’s face it not every slap in the face means the same thing. His attitude is summed up perfectly in this simple poem:

art

as the

spirit

wanes

the

form

appears.

It’s a profound statement, which is why in the 500+ pages of The Pleasure of the Damned you’ll find no sonnets, no sestinas, no haiku. This doesn’t mean that his poems have no shape – the poem above clearly has a shape – but that shape doesn’t have a name; it’s the shape that is natural to that poem.

He also maintained that he wasn’t big on metaphors but the English language is so figurative that they’re impossible to pass up and I can’t see that he went out of way to avoid them:

my goldfish stares with watery eyes

into the hemisphere of my sorrow

from ‘Goldfish’ (He was not big on capital letters but there are a few here and there)

One of the greatest exponents of Bukowski’s writing was the publisher John Martin, “a Christian Scientist who drinks nothing stronger than iced tea.” When he first met Bukowski he wasn’t a publisher, he’d simply read some of his stuff and was blown away by it, blown away enough to seek him out. The first thing Bukowski did when they met, of course, was offer him a beer:

Martin declined, reminding Bukowski that he didn’t drink. ‘That kind of put me off him right there: this guy’s inhuman, he doesn’t drink beer!’ said Bukowski, recalling the meeting.

For his part, Martin was taken aback by Bukowski’s scruffy appearance and the filthy conditions he was living in.

When he asked to see some of his writing Bukowski took him to a closet wherein there was a stack of paper that came up to Martin’s waist:

“What’s this?” asked Martin.

“Writing,” replied Bukowski.

“No kidding?”

“Yeah.”

“How long did it take you to write this?”

“Oh, I don’t know, three or four months.”

If I piled up my entire life’s writing I’d be lucky if it came up to my knees! Anyway, Martin took an extraordinary leap of faith with Bukowski once he had become his publisher. To enable him to quit work and write fulltime they worked out how much Bukowski needed to live – it came to $100 a month – and Martin agreed to pay him that . . . for life. It was a gentleman’s agreement and they stuck to it till Bukowski’s death although the sum increased by steps as his sales did.

Now, none of this is in the book of poetry, there’s not even an introduction by Martin, which it could’ve used, but I think what he did goes some way to prove that there must have been something extraordinary about what Bukowski had to say and that he seemed to have so much to say. What could he possibly have to say that he needed to write so much? The simple fact is that there is nothing that he didn’t consider appropriate subject matter for poetry and, as the best comedians demonstrate daily, there’s nothing that can’t be made interesting if you’re interested in it.

soirée

in a cupboard sits my bottle

like a dwarf waiting to scratch out my prayers.

I drink and cough like some idiot at a symphony,

sunlight and maddened birds are everywhere,

the phone rings gambolling its sounds

against the odds of the crooked sea;

I drink deeply and evenly now,

I drink to paradise

and death

and the lie of love

but few are without humour. As he grew older, and women began to be a part of his life, love poems appear, sex poems, domestic poems, breakup poems and finally poems about fatherhood:

majestic, magic

infinite

my little girl is

sun

on the carpet –

from ‘marina:’

He documented everything but he also had a way of looking at things, even death, for example, here’s the opening to ‘eulogy to a hell of a dame’:

some dogs who sleep at night

must dream of bonesand I remember your bones

in flesh

and best

in that dark green dress

and those high-heeled bright

black shoes,

The fact is he wasn’t really that crazy about dogs; he was a cat person, like me:

remember that

there is acat

somewhere

adjusting to the

space of itself

with a delightful

grace

from ‘in other words’

I was particularly touched by a poem about the death of one of his cats, ‘one for the old boy’, which ends:

the lungs gave out

last Monday.

now he’s in the rose

garden

and I’ve heard a

stirring march

playing for him

inside of me

which I know

not many

but some of you

would like to

know

about

that’s

all.

At times what he has to say is absolutely heartbreaking in its honest simplicity. It’s like when you read a poem like ‘oh,yes’ – the words are so simple and the sentiment so obvious you wonder how you managed not to think that thought for yourself. This is why we need poets, to state the blinkin’ obvious:

oh, yes

there are worse things than

being alone

but if often takes decades

to realise this

and most often

when you do

it’s too late

and there’s nothing worse

than

too late.

A number of the poems are character studies, like ‘the young girl who lives in Canoga Park’ who

...only fucks the ones she doesn’t want

to marry

to the others she says

you’ve got to marry me

or maybe she just fucks the ones she wants

to fuck?

or

there’s Barry in his ripped walking shorts

he’s on Thorazine

is 24

looks 38

people he sees out of the window as he’s typing. Almost all his poems tell stories. In his article on Bukowski in 20th Century American Poetry Michael Basinski called these “narrative vignettes” that expose “the ridiculous in American society”. But his appeal isn’t confined to Americans.

I’m fifty just now and so these few lines from ‘one more good one’ really struck a chord with me:

to be writing poetry at the age of 50

like a schoolboy,

surely, I must be crazy

[...]

I sit between 2 lamps,

bottle on the floor

begging a 20-year-old typewriter

to say something in a way and

well enough

so they won’t confuse me

with the more comfortable

practitioners;

Bukowski has his fans and his detractors. In many respects he was his own worst enemy in that his lifestyle came to overshadow his work. He is imitated more than many would like to admit but I wouldn’t be too quick to think if you adopt his lifestyle you’ll automatically start churning out poems at the same rate he did. When the drinking dried up and he cleaned himself up, when he had money to burn and a stable relationship he continued to work. In an article in The Guardian, Tony O’Neill had this to say:

Of course, there are a lot of bad poets in thrall to Bukowski - after all, his great skill lay in making the writing of great poetry seem easy. Poets who affect his lifestyle without learning the craft of writing do so at their peril. And don't look to the man himself for clues on where the poems come from: he once said that writing a poem is "like taking a shit, you smell it and then flush it away ... writing is all about leaving behind as much a stink as possible". – 'Don’t Blame Bukowski for Bad Poetry', The Guardian, 5th September 2007

Bearing this in mind I found an amusing – and please tell me, tongue-in-cheek – wee article entitled How to Write Poetry Like Bukowski which I’ll summarise here:

- Boast about yourself

- Take boasting to another level. Exaggerate.

- Write about women

- Write about hardships

- Use daily experiences as motivations

Personally I would’ve thought the #1 would have been ‘Get drunk. Stay drunk’ but there you go. I have no doubt that any attempt to turn what he did into a formula would set him off on a rant. I think even the idea that he was a trend-setter would have bothered him.

Bukowski approved of large collections of his poetry and I doubt there are any collections bigger than this one. One of the reasons a large collection works is that, as Adam Kirsh put it in The New Yorker:

Bukowski’s poems are best appreciated not as individual verbal artefacts but as ongoing instalments in the tale of his true adventures, like a comic book or a movie serial. They are strongly narrative, drawing from an endless supply of anecdotes that typically involve a bar, a skid-row hotel, a horse race, a girlfriend, or any permutation thereof. Bukowski’s free verse is really a series of declarative sentences broken up into a long, narrow column, the short lines giving an impression of speed and terseness even when the language is sentimental or clichéd. The effect is as though some legendary tough guy, a cross between Philip Marlowe and Paul Bunyan, were to take the barstool next to you, buy a round, and start telling his life story. – ‘Smashed’, The New Yorker, 4th January 2010

The thing about Bukowski, as his publisher, John Martin put it, “he is not a mainstream author and he will never have a mainstream public.” The world is growing and a lot of people now constitute the not-mainstream. Millions have bought his books. However, after reading about his life I can see a real dichotomy when it comes to Bukowski. I’m tempted to think that he played a part for all his life but couldn’t hide the other side of himself. He was well-read – “Between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four I must have read a whole library,” he admitted – and had a good knowledge of classical music – I’ve so far spotted Wagner, Verdi, Hugo Wolf, Donizetti, Hindemith, Chopin and Bruckner in this collection – and particularly from his letters it turns out that he revealed himself to be quite the Bohemian™ intellectual even if he did try and play down the image. Here’s a poem about Prokofiev that’s not in the collection:

three oranges

first time my father overheard me listening to

this bit of music he asked me,

"what is it?"

"it's called Love For Three Oranges,"

I informed him.

"boy," he said, "that's getting it

cheap."

he meant sex.

listening to it

I always imagined three oranges

sitting there,

you know how orange they can

get,

so mightily orange.

maybe Prokofiev had meant

what my father

thought.

if so, I preferred it the

other way

the most horrible thing

I could think of

was part of me being

what ejaculated out of the

end of his

stupid penis.

I will never forgive him

for that,

his trick that I am stuck

with,

I find no nobility in

parenthood.

I say kill the Father

before he makes more

such as

I.

I have found reading this poetry collection to be refreshing. I suspect that he might get old quick and that I won’t be looking to supplement this volume any day soon but I can always move onto his prose. I think he’s an important poet and has things to say that people who never read poetry would appreciate and get. What he’s not, as the back of this collection says that Jean Genet said he was, is “the best poet in America,” nor was Jean Paul Sartre a fan of his work as Bukowski informed his readers. As Sounes notes in his biography:

Leading world experts on the lives and works of both Genet and Sartre have no knowledge of either writer ever having said anything about Bukowski.

In the source notes to his book (which Canongate also published) he details the lengths he went to to try and find some corroboration of these claims but none could be found and it looks like Bukowski simply made them up. So, tsk, tsk, Canongate. (Their managing editor admits that one slipped through the cracks and will be changed on the next edition.)

He is not without his detractors. The noted Bukowski critic, the poet and editor of The Melic Review, C.E. Chaffin, offered a blistering critique in a famous tri-partite decimation:

I should first remind the reader that he may be the best known American poet in Europe today, and for two reasons: 1) His language is simplistic; and 2) The attitude in his main body of work matches the prevailing atheistic pessimism among intellectuals on the continent. It is not Bukowski's renown I question, an unreliable indicator of quality in any case, but 1) His lack of craft; 2) His lack of transcendent values; and 3) As above, that he represents the final breakdown between life and art in poetry. – ‘The Bukowski Divide: Poetic Genius or Literary Sacrilege?’, Scottish Poetry Review

The main response I would give, without wanting to get into a fight, is: Are these necessarily bad things? For Bukowski his publisher’s teetotalism made no sense to him (what did the man do if he didn’t drink?) in just the same way that a Christian’s belief in God makes no sense to an atheist. There was a time when the atheist would have been in the minority and people would have pointed fingers at him and considered him odd but nowadays I always hear a note of surprise when someone finds out about someone being a Christian. Times change. Opinions change. Change is not a bad thing, not necessarily.

In his defence Jay Dougherty identifies trademark Bukowskian qualities:

A keen ear for the musical quality of natural, everyday speech; an ability to infuse significance into desperate, dreadful moments of his own life and those of others without becoming bathetic or sentimental; a tremendous facility of listing and juxtaposing details of everyday life with abstraction either to set a scene or to vivify a theme; an artistic distance from his subjects which allows him to find humour and nuggets of wisdom in even the most dismal scenario, his own or others. – ‘The Bukowski Divide: Poetic Genius or Literary Sacrilege?’, Scottish Poetry Review

What he has for me is the same thing that I discovered forty years ago in Larkin, that poetry can be found in the most banal of things. I have no doubt that there were many ‘Mr. Bleaney’s’ kicking ‘Toads’ around Bukowski’s neighbourhood.

Probably one of the wisest (and perhaps, safest) things ever said about Bukowski was by Jim Harrison in the New York Times:

I am not inclined to make elaborate claims for Bukowski, because there is no one to compare him to, plus or minus.

and there have been many writers and artists who that could also be said of like Cummings or Brautigan; who would you compare Jackson Pollock to or Charles Ives? Imitators of all these have appeared on the scene as you might expect but you can’t criticise the artists for inspiring people no matter how poor the imitations are.

Most of the poems in this collection are a page or two pages in length with short lines and a lot of white space so it’s a surprisingly quick read but it’s not a volume I’d recommend rushing. Having read the biography beforehand did stand me in good stead but I wouldn’t say that you need to know a great deal about him up front to enjoy these.

I’ve finished the book now and I have six bookmarks left, poems that I would really like to share with you but I’ve not got room for six so I’ve picked two, a short one and a not so short one that covers material I’ve not touched on so far. It was not an easy choice.

about the PEN conference

take a writer away from his typewriter

and all you have left

is

the sickness

which started him

typing

in the

beginning.

safe

the house next door makes me

sad.

both man and wife rise early and

go to work.

they arrive home in early evening.

they have a young boy and a girl.

by 9 p.m. all the lights in the house

are out.

the next morning both man and

wife rise early again and go to

work.

they return in early evening.

By 9 p.m. all the lights are

out.

the house next door makes me

sad.

the people are nice people, I

like them.

but I feel them drowning.

and I can’t save them.

they are surviving.

they are not

homeless.

but the price is

terrible.

sometimes during the day

I will look at the house

and the house will look at

me

and the house will

weep, yes, it does, I

feel it.

the house is sad for the people living

there

and I am too

and we look at each other

and cars go up and down the

street,

boats cross the harbour

and the tall palms poke

at the sky

and tonight at 9 p.m.

the lights will go out,

and not only in this

house

and not only in this city.

safe lives hiding,

almost

stopped,

the breathing of

bodies and little

else.

Needless to say a huge number of poems are available online and here is as good a place as any to start looking. There are also plenty of videos showing him reading.

If you are looking for a decent collection of Bukowski’s poems then this looks like as decent a collection as any. It was collated by his editor John Martin (who I assume is still a teetotaller) but I doubt many have read as much of Bukowski’s work as he has. It doesn’t dwell too much on any one area although dog lovers may find the number of cat poems disturbing.

The Pleasure of the Damned: Poems, 1951 – 1993 is available in the UK from Canongate Books for a not-unreasonable £14.99.

24 comments:

Never read that last poem. It's a beauty. All our lives can't be fireworks. Tragic and beautiful and funny.

Good review. I read that Sarte wanted to meet Bukowski and he declined. Interesting to note it might be a lie/error. (Psst, I know some people are bukowski.net who might well have information on this piece. People there who collect and research every aspect of his life. Hell, some of them even knew him...vaguely. They might make an appearance on your blog. Never know.)

You've caught the man well, his directness, his honesty, his ability to take seriousness and expose it as a fragile crowd of people. I think those that decry bukowski are in denial. They don't like the unflinching directness. He rips the trousers off pretense with his ordinariness of pretense.

Shithot, Jim. I haven't bought this one Don't think I will.

p.s. Bukowski was not a beat poet. They were bohemian. Much as he was. But Bukowski was also, working class poet. American rhetoric uses - 'skid row' 'low life' because it can't bring itself to see the American dream exposed as purile fantasy. He was a working class poet.

Keep up the good pen. May your keyboard sing more songs than tears.

Interesting to read your take on Bukowski. I'm a huge fan of his poetry (but not of his prose.) I think that perhaps it's because I find poetry sometimes quite difficult to understand, whereas with Bukowski it is so powerfully clear.

People make a huge mistake, in my opinion, when they underestimate his care and crafstmanship. He has so many terrible imitators who believe that chucking words on a page when sozzled is all it takes. Wrong, wrong, wrong.

I think one of his stand out poems is:

Death Wants More Death

Death wants more death, and its webs are full:

I remember my father's garage, how child-like

I would brush the corpses of flies

from the windows they thought were escape-

their sticky, ugly, vibrant bodies

shouting like dumb crazy dogs against the glass

only to spin and flit

in that second larger than hell or heaven

onto the edge of the ledge,

and then the spider from his dank hole

nervous and exposed

the puff of body swelling

hanging there

not really quite knowing,

and then knowing-

something sending it down its string,

the wet web,

toward the weak shield of buzzing,

the pulsing;

a last desperate moving hair-leg

there against the glass

there alive in the sun,

spun in white;

and almost like love:

the closing over,

the first hushed spider-sucking:

filling its sack

upon this thing that lived;

crouching there upon its back

drawing its certain blood

as the world goes by outside

and my temples scream

and I hurl the broom against them:

the spider dull with spider-anger

still thinking of its prey

and waving an amazed broken leg;

the fly very still,

a dirty speck stranded to straw;

I shake the killer loose

and he walks lame and peeved

towards some dark corner

but I intercept his dawdling

his crawling like some broken hero,

and the straws smash his legs

now waving

above his head

and looking

looking for the enemy

and somewhat valiant,

dying without apparent pain

simply crawling backward

piece by piece

leaving nothing there

until at last the red gut sack

splashes

its secrets,

and I run child-like

with God's anger a step behind,

back to simple sunlight,

wondering

as the world goes by

with curled smile

if anyone else

saw or sensed my crime

By the way, Buk is one of the most stolen authors in our bookshop!

I appreciate your review here, because I think it's pretty balanced. Most of the flaws you point out in Bukowski's work are right on, and so are the virtues. I think you see the writing and the man pretty clearly.

The thing I always notice, though, is that many of the people who really adore him seem to do so because of reasons not really having to do with the quality of the poetry itself. (The comments so far reflect this.) It's almost as though he was a hero, not a poet, because he was a manly man, or because he was a blue collar working class drunk who wrote poems, or because of other factors totally external to the poems themselves. People often praise Bukowski in the same breath that they put down many other styles of poetry—as though his clarity and simplicity were an innate virtue in poetry. What these folks always seem to miss is that poetry is not prose, and doesn't have to be. I always find it interesting when people praise the prose-like qualities of Bukowski's poetry—what they're really saying is that they hate "poetry," and they like his brand of anti-poetry. I find it amusing when some folks praise his poetry while at the same time saying they don't like his prose—when in fact the main difference between the two is line-breaks. Otherwise, they're almost the same.

You know, it's parallel to the way that some writers adore Hemingway not because he was a great writer but because of the values he espoused, and acted out, external to what he actually wrote. The reputation of the man apart from the writing strongly colors the response to the writing. It's very hard to read Bukowski (or Hemingway) without bringing in the mythology surrounding the man. And many fans are really stuck on the mythology of the man—in both cases, a self-created mythology that may or may not have been biographically accurate on many points—rather than on the quality of the writing itself.

Which in Bukowski's case was very uneven. And often quite clichéd. (And I have the single volume of Hemingway's poetry ever published, and let me just say, Hem was a lousy poet.)

I've read a few other biographies of Bukowski, and lots of his writings. He wrote some great individual poems. The difficulty I cannot get past is that, as great as he could sometimes be as a writer, he was almost always a shit to his friends. He ended many long-term relationships, including with those who helped make him a famous writer by getting him published, because for one reason or another they pissed him off. Usually when he was drunk. The man was his own worst enemy. He could occasionally write like an angel. And I could never have stood being one of his abused friends.

For the record, I don't think the difference between his poetry and his prose is line-breaks. What I admire about his poetry has everything to do with, erm, the poetry. It's not anti-poetry.

Neither do I hate poetry. I merely said that I sometimes find some poetry difficult to understand, and I was wondering if the clarity was perhaps why I feel so attracted to Bukowski's. I have no attraction one way or another to the "myth" of the man. I don't respond to poetry according to personality or history, I respond to the words. It's rather dismissive of you to read a brief comment I have made here and stick me in a little box of your own creation.

Boo, to Art!

I'm don't praise him as a hero, but simply as a man, when I first read him, I had no idea who he was or of his mythology. Bukowski has a directness, a lack of flower arranging metaphors, and this is not so common in poetry or wasn't. Most peotry avoids the issue.or swamped you with obsucrantism

Anyway, deny it all you want, I don't worship him, I just find so much wisdom, cutting through the bullshit, cutting through the dead intellectualising. We could all do with a bit of that, yeah, Art?

Jim,

thanks for dropping by at PiR.

Roddy Doyle, 6 page introduction, is full of praise for Bukowski's autobiographical novel Ham on Rye: 'his best writing' says Doyle.

McGuire, it’s been a long time since any poet has had such an impact on me and it’s obvious he aspires to a high level of honesty but the fact that he would make up quotes amuses me more than anything else. I’m known as an honest person but I lie all the time, small lies, inaccuracies really, but I’m sloppy, I pick a word that’s close enough to what I mean and let that ride.

Sara, ‘Death Wants More Death’ is one of the poems in this collection. It’s certainly one of his best opening lines. It’s hard to decide what to choose when you have a book with over 400 poems in it. I love his clarity and am so impressed that he managed to work while sozzled. Not that being a drunk is something to be admired but if you manage to be one and get the job done then more power to your elbow as they say over here.

Art, I wish that prosers and poets would stop arguing, I really do. Yes, undoubtedly there is a prosaic quality to Bukowski’s poetry in that he eschews most poetic techniques apart from metaphor which is pretty much unavoidable no matter what you write. Since I’ve read none of his prose work I can’t comment but I suspect you’re being a little harsh there. That said I would like to read a good defence of Buk’s use of line breaks. If we just take the poem Sara posted it looks like he’s using natural pauses as line breaks. The acid test for me is where you reformat a piece to remove all line breaks and if it still feels like a poem then it’s a poem. I still haven’t got to grips with the concept of prose poetry but I will research it one of these days.

And, Poet in Residence, thanks for that. I have more books to read just now that I know what to do with but I’ll bear what Doyle said about Ham on Rye in mind. My wife’s son has all his books. I must talk to him about it one of these days.

Oh, and Sara, McGuire, Art – play nice. There’s room in this world for all opinions.

Great post, Jim. I know very little about Bukowski, so thanks for this.

Thank you for that, Sorlil, I felt the same. That's another one off a very long list of writers I know nothing about.

I remain unconvinced by any of that, McG. In fact, you sort of prove my point. LOL Claim all you want that you're not a Buk-disciple, but your own rhetoric puts the lie to that claim. I guess I touched a nerve. LOL

Jim, I agree: The whole prose/poetry argument is uninteresting in the extreme, anymore. Yet it does keep coming up, because so many in each camp are so committed to being right about their positions.

You wrote:

"The acid test for me is where you reformat a piece to remove all line breaks and if it still feels like a poem then it’s a poem. I still haven’t got to grips with the concept of prose poetry but I will research it one of these days."

I submit to you that you HAVE come to grips with prose-poetry, because your acid test is pretty the definition of prose-poetry. Which is poetry structured like prose. QED.

By the way, your definition of what is good and bad in poetry ALSO proves my point: it's precisely the sort of thing I was talking about. Your definition about what's wrong and right in contemporary poetry is very correct—with regard to the kinds of poems it refers to. But it also sets up a straw man that doesn't hold water. But whatever. I don't expect to change anyone's fixed opinions.

As for my opinion, I was responding to the idea brought upI have read Buk's prose and his poetry, and I stand by my opinion. I'm not the only reader who has said that, either. I don't think I'm being harsh, I think I'm being as honest as Buk himself could be. Based on what I've read of his opinions about his own work, I also don't think he'd completely disagree. The assumption should not be made that prose is less than poetry, after all, or that in Buk's case that his poetry is lessened by being like his prose. Speaking of those prose/poetry arguments, I've heard many poets say that lots of poetry really IS like prose broken into lines—but that doesn't always means it's bad, therefore.

Of course, once again, his imitators are much worse at it then he was. You were right to point out that he gets away with a lot of prosaic writing that verges on clichés, etc., because of his flare and his way of being honest—and he DOES get away with it. He pulls it off, often enough to be remarkable. usually his imitators don't, though, and that does cloud the waters.

The great thing about opinions, Art, and also the worse thing, is that they can’t be wrong; they may be misguided but never out-and-out wrong. I’m always keen for people to explain their opinions. I hate the well-that’s-just-what-I-believe-and-you-can-take-it-or-leave-it stance. I am genuinely interested in why people love of loathe the things they do. The one I always cite is opera because I do not see the attraction and can tolerate very little of it (particularly if sung in English) but I am fascinated by how devoted people can be to it. It’s rather snooty of me to use that as my example because I could say the same for rap music and death metal but because I’m so into classical music in general I feel I should be able to appreciate opera. I’m not dead yet. I have time.

As for what poetry may be, on his blog Ron Silliman posted a link to a series of videos called ‘Poetry is’, ‘Music is’ and ‘Art is’ which I think you might appreciate. I’ve only watched the ‘Poetry is’ one and it was fascinating, 81 minutes of poets trying to define their craft, some more ably than others. But why no ‘Prose is’ I wonder? Perhaps because once you’ve agreed on a definition for poetry everything else must be prose.

People use the word 'love' freely in blog comments. I try to use it sparingly but it feels apt here.

I love Bukowski's poetry, at least I love the little I've read here in your review.

I'm also fascinted by the story of his lifde converted into verse - that stuff about his resentment of his father in the three oranges: the most horrible thing

I could think of

was part of me being

what ejaculated out of the

end of his

stupid penis.

I will never forgive him.

This is onderful. Bukowski is a man after my own heart, notwithstanding his gross behaviour when drunk.

I'm amazed that people imagine they can emulate him simply by getting drunk and trying to write poetry.

Sometimes when talent abounds parallel to problems, critics like to put the two together to somehow even out and remove the level of talent that's evident.

Three cheers for Bukowski. I'm sad he's dead, and I'm sad for him that he had such a toughh life, but I wonder without could he have produced the poetry without it.

Thanks, Jim.

Indeed, Elisabeth, ‘love’ is one of the words I bitch about more than any other. People chuck it about willy-nilly. They do the same with ‘friend’ devaluing the word completely. I don’t believe in love at first sight not friendship at first sight. I do believe we can recognise a kindred spirit at first sight but real relationships take time to develop.

As an aside do check out the animated film Mary and Max if you want to see a wonderful film about the most unlikely of friendships. The film takes place from 1976 to 1994 and tells the story of the unlikely pen-pal friendship that lasts for 18 years between Mary, a chubby lonely 8-year-old girl who lives in Mount Waverley, a suburb of Melbourne, Australia, and Max, a 44-year-old, severely obese, atheistic Jewish man with Asperger syndrome who lives in New York City.

Back to the Bukowski: I knew you’d appreciate his attempts at honesty in his poetry. I’m only sorry I didn’t discover him sooner. I don’t think my style would’ve changed – I’m really not heavily influenced that way – but I don’t think it would have done me any harm either. Actually the first thing I did when I finished the collection was write a poem ‘this is not a Bukowski poem’ but you’ll have to wait for an upcoming blog to read that.

As for the romantic notion of the alcoholic writer I have written about this at length already in the post ‘Portrait of the writer as a drunken skunk’ parts one and two. I simply don’t get it. Carrie and I watched an episode of Grey’s Anatomy on TV last night and there was a scene where one of the doctors placed a glass of whisky in front of an alcoholic and dared him not to drink it. And I looked at the liquid in the glass and the way the light caught it and I thought how beautiful it was. And then I remembered just how horrible whisky tastes – a Scotsman who doesn’t like Scotch, go figure.

You did touch a nerve and I was too quick to jump to his defense, in fairness, you make a balanced criticism of him.

I resent the implication I'm imitating him though...that's baloney, as Judge Judy would say.

I just think he is so easily dismissed yet at the same time I know he IS worshipped and adored. I should just be content with what I love from it, and leave the aruging to other people.

Concedes to be petulant,

McGuire.

I think Bukowski's poetry, from the little I've read here in this post, is very interesting. I am by turns touched and repulsed by his poetry but that only tells me that I am affected by it. I really need to read more for myself now.

As for craft - there are times when the lines distract from the words - when I cannot absorb the words for noticing the structure of the lines - especially in the Three Oranges. How out of seven sentences beginning with "I", all but one of them begin a line. But then the words, when I force myself to ignore the structure, are something else altogether. I wish he had let the lines run on longer. He was not a pretty poet, nor is his poetry (the little I've now read) pretty but it is poetry. I think that should be enough. I don't need to know about a poet to find merit in his/her work, I need only to open my eyes.

You know, Rachel, there are times when I wish poetry had stuck with its rules so that you could look at a poem, know it was a sonnet, for example, and know what to expect from that sonnet. Since the rulebook was tossed how do we gauge good or bad poetry especially since even bad poets will defend their writing tooth and nail? I know I would when I was starting out to a ridiculous and embarrassing degree. I don’t get why most poets break their lines where they do and I find few willing to talk about it like it was the secret formula to Coke or something. When I started off my line breaks came where they felt ‘right at the time’ as if ‘at the time’ I was super-sensitive and knew intuitively what was right. That’s basically what I believed, that inspiration came upon me and I had to work quickly before I used it all up.

My gut feeling, based on what I read in his biography, is that Bukowski didn’t fret for weeks over whether it should be ‘in a minute’, ‘in a moment’ or ‘in a second’; he just picked one and didn’t look back and the same with line structure. I’m not saying that no thought went into it but I don’t think he would have lost sleep over where the pronouns fell in ‘three oranges’. This is where I felt a little let down by his biography because I had questions about how he worked. That Sounes doesn’t talk about it makes me feel that he did just dump words on a page and not look back afterwards and if he happened to write a poem then good and well and if it happened to be crap well he’d just write another one.

“the shortest, sweetest, bangingest way” to say what he wanted to say. seems to me like a near perfect description of what a poem should be.

I can see why it might be said, but I do not see his poems (those that I have seen here) as chopped-up prose.

If I'd written them I am sure I would have broken the lines differently - but that's another story.

I think he might repay a bit of study - but whether I'll get round to it is also another story.

Poet in Residence, I think you may have hit on the key element in Bukowski’s poetry because you could say that about a lot of my own poetry, pop-psychology mixed with pop-philosophy. Hemmingway has never done much for me. I’ve only read A Farewell to Arms and it really didn’t excite me at all.

I think there are a lot of people, Elisabeth, and a lot more these days than there used to be, who achieve a level of fame because they have talent but stay famous because of the lifestyle they adopt afterwards. Like Oliver Reed who “could have been a contender” to quote On the Waterfront but gave way to the drink and never rose to the challenge.

And, Dave, yes, the blessed line break. There was a time a while back where I seriously considered giving up on them completely. But you’re right: “shortest, sweetest, bangingest” is just a brilliant description.

'[H]is lifestyle came to overshadow his work.' For a long time that shadow kept me from an objective reading of his work. But, as you demonstrate here, so much of the poetry is tender, whimsical, humorous, majestic and though I came to it late, I was so glad to have done so.

As I think I've said already, Dick, I regret letter just the suggestion of his reputation putting me off. Anyway I've found him now and glad I have.

Jim,

Do you know Buk's poem "So You Want to be a Writer?".

It's probably googleable. If not I'll have to type it. It's quite long.

In Part 2 of "Charles Bukoski New Poems Book 1" (Virgin Books) there's an introductory:

if I bet on Humanity

I'd never cash a ticket

all the best,

Gwilym

A good one to highlight, Gwilym. You can read it online here.

I'm afraid I still get my wife to read everything so I guess I've got a bit to go, eh?

"my goldfish stares with watery eyes

into the hemisphere of my sorrow"

Oh my. Oh, and cats are made to be a study in psychology and are hard for other people to understand. Hmmm... Bukowski is too? :)

He kind of reminds me of an older version of Shel Silverstein -- out there and down-to-earth at the same time, except Bukowski seems a little more down-to-earth; perhaps that was out of necessity.

Thank you. Still trying to digest this. It's all so troubling and admirable at the same time.

Where did you acquire all of these intelligent, eloquent readers? Just an observation. Think I need a Blogger blog. Love mine as I do, its focus is just way too narrow for my fascination with you guys! :)

I have to say the name Shel Silverstein meant nothing to me till I looked him up in Wikipedia, Evelyn. I don’t know him as a poet but as a songwriter, yes. The closest I would think we had to him in the UK would have been Spike Milligan.

As for my readers, yes, I have a good crowd and what’s more, they all have interesting blogs too – you should subscribe to a few of them.

Post a Comment