Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, was my early world. Today it’s still the wallpaper in my brain – John Michael Cummings

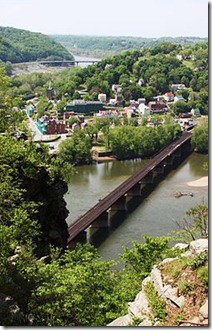

The historic town of Harpers Ferry is located in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains (the ones Laurel and Hardy sang about) in Jefferson County, West Virginia, situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers where the states of Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia meet. So, most definitely, a nexus. Historically, it is best known for John Brown's raid on the United States Armoury and Arsenal in 1859 which, while unsuccessful in inciting a slave revolt, was a precursor to numerous epic battles of the American Civil War which resulted in the eventual emancipation of slaves in the United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the town had a population of 286, a fall from a massive 315 in 2000; the population is, however, predominately white. It is surrounded by the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park which covers almost 4000 acres. Needless to say, it is a major tourist attraction; in fact Thomas Jefferson wrote, “The passage of the Potomac through the Blue Ridge is perhaps one of the most stupendous scenes in Nature ... This scene is worth a voyage across the Atlantic.”

So, a very beautiful place from all accounts but I’ve seen Blue Velvet (which was set just up the coast in New Jersey) and I know that beauty is skin deep and often enough ugly things take place under a veneer of civility and respectability in small town America.

So, a very beautiful place from all accounts but I’ve seen Blue Velvet (which was set just up the coast in New Jersey) and I know that beauty is skin deep and often enough ugly things take place under a veneer of civility and respectability in small town America.

In the introduction to his semi- autobiographical novel in which he revisits the twelve-year-old boy he remembers himself being while growing up in Waukegan, Illinois (which is not that far from Harpers Ferry), Ray Bradbury has this to say about the nature of ugliness:

I was amused and somewhat astonished at a critic a few years back who wrote an article analysing Dandelion Wine plus the more realistic works of Sinclair Lewis, wondering how I could have been born and raised in Waukegan … and not noticed how ugly the harbour was and how depressing the coal docks and railyards down below the town. But, of course, I had noticed them and, genetic enchanter that I was, was fascinated by their beauty. Trains and boxcars and the smell of coal and fire are not ugly to children. Ugliness is a concept that we happen on later and become self-conscious about.

That was 1928, the year before the Great Depression. Bradbury wrote those words in 1974 which is just a couple of years before the events recorded in Ugly to Start With, John Michael Cummings’ short story collection, are set. The protagonist here is slightly older than Bradbury’s alter ego, Douglas Spaulding; Jason Stevens is about thirteen at the start of the book although, since he moves from the Ninth to the Tenth grade, he’s probably fourteen once the events chronicled in the collection conclude since the stories appear to follow a chronological order. Although, in the strictest sense, this is not a novel, it does have the feel of one especially since, on the whole, the stories are slices of life; vignettes rather than plotted constructs. That said all the pieces in this collection have been published as standalone works, mostly in print journals, but a few are available online.

I asked John (who’s apparently a fan) what he thought about Bradbury’s comment. His response:

He's right about ugliness. We're taught it, just like hate and shame and fear. I think love and enchantment grow in us on their own, like happy spores.

He calls himself a "genetic enchanter," which sounds like a naturally happy boy. I had a terrifically unhappy father darkening my childhood. He managed to pass on some of his self-conscious ugliness.

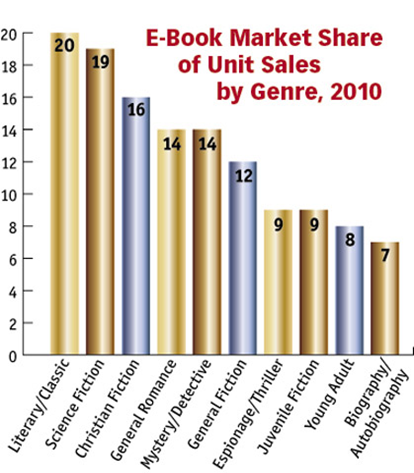

Ugly to Start With is aimed at that awkward-to-define demographic, the young adult. I didn’t know this when I read the book. In fact I made a point of taking in as little as possible before I opened it and it was only once I was done and decided I wanted to review it that I started to research the author. I asked John what age group he felt the book was suitable for and he wrote back, “Age group is hard question to answer. I guess ages 12-14 is a good range. But maybe 10-16. I have no problem saying that to parents.” We’ll come back to this.

The protagonist in this book is not blind to the world around him. But this is not 1928. In Bradbury’s novel the word ‘ugly’ appears only once to describe some furniture. Jason, on the other hand, sees that there is as much ugliness around him as there is beauty. This is how he describes his parents’ house in the story ‘Two Tunes’:

Our front porch had a real hillbilly look, too, but that in itself was never a problem. We had a maple tree out front to keep tourists from seeing the dirty plastic covering the windows, the white extension cord holding up the rain gutter, and the junk stacked everywhere. We had that tree to hide the heaps of ugly firewood thrown up on the porch and the Band-Aid tan paint Dad mixed from several leftover paints and used on the porch railing and window trim. We had that tree to cover the strange damp stain across the rock face of our house, a stain somehow caused by the mouldy hillside behind us. We had that tree to cover up our dog Barfly, too—named for what he did best, running the flower bed bare, choking himself on his own chain, then throwing up. We had a tree for all this. One big tree.

So he is conscious of the ugliness under the surface. We witness another instance much later in ‘The Scratchboard Project’ when Jason, due to dallying and not choosing his own partner, is told by his teacher he has to sketch one of the girls from his class, a black girl from a poorer neighbourhood, whose beauty, which he had somehow never been able to see in the classroom, becomes apparent in the relaxed atmosphere of her home where she models for him posing in a variety of wigs she happens to have at her disposal. All is going well until her big brother decides to be mischievous:

Just then, Tyrone’s big black arm came down from above, yanked off her wig, and disappeared up the ladder with it. She screamed and tried to cover her head with her hands, but not before I saw the ugly white scar across her scalp and the mangled hair growing around it. I couldn’t take my eyes off it. It was the ugliest sight—hair and white skin smeared together as if her head was made of melted wax. And where there wasn’t a scar or messed up hair, there were pasted down cornrows that made her head like a boy’s.

She screamed at me to stop gawking, stomped her feet in a crazy fit, all while trying to grab another wig from the drawer. But she ended up putting on the funny red wig, which made the moment worse.

How to deal with this? How would his family deal with this? How did they deal with Skinny Minnie the silver tabby that started slinking around the house, as cats do, gradually insinuating itself in the family’s affections? At first everything was fine and then the cat started to get into scraps:

How to deal with this? How would his family deal with this? How did they deal with Skinny Minnie the silver tabby that started slinking around the house, as cats do, gradually insinuating itself in the family’s affections? At first everything was fine and then the cat started to get into scraps:

Sometimes whole days passed, and she didn’t show up, and I forgot about her for a while. Then she came back, looking worse than ever. Her soft, perfect coat was matted with sticks and dried blood. She had a limp, too, and half an ear was missing. I couldn’t bear to touch her, couldn’t stand having her near me, either. All she did was sit there and moan, her wounds oozing.

[…]

My body shuddered. If only she would die, then I wouldn’t feel the embarrassment anymore. That’s how my family was. Whatever it was, if it was ugly to start with, or turned ugly, we were ashamed of it and wanted it to go away.

The irony, of course, is that his family is not exactly a pretty one either. Jason’s father, for starters, is a drunk and a womaniser:

My father was crazy all right. Everybody knew that. Ever since Mom threw him out of the house last year over Mrs. Jackson, he had been living on his mountain property. Soon after, he got suspended from his job at the post office because of his drinking. He was never coming back, or at least I hoped he was gone for good. But like everything else in the rotten West Virginia woods, his ugliness would probably creep back into our lives.

and, so it’s not so surprising that when his son looks in the mirror this is what he sees:

It didn’t mean I was normal either. If I was ugly, then that was why. But when I looked at myself in the mirror, I didn’t think I was ugly, maybe a little soft-faced here and there, even girlish around the eyes, but not plain ugly. Still, since this was happening, Lisa must have been a fluke. Pam, too.

What is ugliness if not a deviation from the norm? There is nothing a teenage boy wants more than to be normal, to conform, to give no one cause to point the finger or, perhaps worse, wag the finger. And yet, at the same time, what he really wants more than anything is to find himself even if that self is a deviant which is perhaps why, in the story ‘Carter’ from which that last quote came, Jason allows himself to be preyed upon by Carter Randolph an old, fat, “fag” to use Jason’s word for him, whose A-frame house he chances upon in the woods one day. When he chances upon Carter the old man is bedecked in ridiculous lemon-coloured trousers but all the man does is point the boy in the direction of the Kennedy place which is where Jason says he’s headed. He doesn’t lay a finger on the boy or try to engage him in conversation but something draws Jason back later that evening to spy on the old man reading and then again, the next evening, in broad daylight so as to make certain they would run into each other. Is it any small wonder that a few days later he is drawn back? Or pushed, since, to be fair, Carter does nothing but be sociable, asking after the boy’s mother and making small talk. But it seems Jason can’t leave well alone and soon he is inside Carter’s house and the conversation turns onto sex:

What is ugliness if not a deviation from the norm? There is nothing a teenage boy wants more than to be normal, to conform, to give no one cause to point the finger or, perhaps worse, wag the finger. And yet, at the same time, what he really wants more than anything is to find himself even if that self is a deviant which is perhaps why, in the story ‘Carter’ from which that last quote came, Jason allows himself to be preyed upon by Carter Randolph an old, fat, “fag” to use Jason’s word for him, whose A-frame house he chances upon in the woods one day. When he chances upon Carter the old man is bedecked in ridiculous lemon-coloured trousers but all the man does is point the boy in the direction of the Kennedy place which is where Jason says he’s headed. He doesn’t lay a finger on the boy or try to engage him in conversation but something draws Jason back later that evening to spy on the old man reading and then again, the next evening, in broad daylight so as to make certain they would run into each other. Is it any small wonder that a few days later he is drawn back? Or pushed, since, to be fair, Carter does nothing but be sociable, asking after the boy’s mother and making small talk. But it seems Jason can’t leave well alone and soon he is inside Carter’s house and the conversation turns onto sex:

“You ever want to make it with a man?” he asked.

The question came fast, out of nowhere, but what surprised me was that I didn’t feel uncomfortable with it. Actually, I was amused, amused by his angle. I knew what he was and what he was doing. He was an old pervert, and he was after me, but he was foolish for thinking I didn’t see through his scheme. He could ask or say whatever he liked. All of this was better than hacking weeds for my father.

Little happens this day but the next day the boy returns fully aware of what might happen. And it does. Well, something does. This is where a lot of people are going to wonder about John suggesting that this book is suitable reading material for the lower end of the young adult range. I think that a ten-year-old would read this book superficially and probably be uncomfortable with the idea of an old homosexual manhandling a young boy. I suspect that most teenagers, however, would shrug it off these days. That said this is what a fifteen-year-old girl who reviewed the book on her own blog, had to say:

I was uncomfortable with some of the situations and subjects; in particular the chapter regarding Carter. Truthfully I had to skip it and I don't think I could have read that bit. It was just too ... mature, disturbing? There was an excessive use of cursing in here that made me squirm too, I mastered the ability to fly over the words I didn't want to process.

I get that and she did the right thing—for her. It is probably the key story in the whole book, though, because of the fact that Carter is old and not conventionally attractive, if at all. But then neither are most witches in fairy tales and yet often innocents are dawn to them. I mention this because of how Jason describes Carter’s house when he first sees it:

Cool. Weird. I had always loved the idea of a house shaped like an “A,” the A being the superior grade, the first letter, and a house boldly taking its shape from it. I stepped closer to it, watching it rise higher and higher above me. This was another kind of fairy tale, a fairy tale with flair.

In fairy tales the wicked witch, the evil troll, the big bad wolf always gets their comeuppance but what’s interesting—and disturbingly believable—here is that, as far as we get to hear, nothing happens following this instance with Carter. There are no consequences. What happened in the woods is never mentioned again; there is no indication that Jason spoke of it to anyone or that Carter got in trouble.

In the next story, ‘Indians and Teddy Bears Were Here First’, life moves on regardless. His grandfather has returned to the area after losing himself after the death of his wife; he has what is probably best described as a late-life crisis:

He traded in his old car for a flashy new one and took half a dozen trips to Florida. With Grandma, the farthest he had ever gone was twenty-two miles to Berryville, Virginia, for the Apple Blossom Parade. He started wearing tight white pants, behaving like a man half his age. He even sold the treasured old Harpers Ferry house he and Grandma had lived in for forty years and moved—not saying where for the longest while. Mom said good riddance. She thought he was perfectly ridiculous.

When he returns a year later it’s not alone—he’s landed a rich widow on his travels, his own personal Golden Girl—and since he doesn’t come a-calling, Jason decides to track him down—“I could find anyone in this town”—only to discover that Granddad’s relocated to the newly-built Sunrise Hills Private Community:

As I passed through the main gate, I felt I’d entered a futuristic world. Spotless grass. Trees that looked cloned. No broken glass on the street. It was a night and day difference compared to the old houses on Tarton Street. Made me wonder who would put a private community so close to the worst houses around, where it would gloat about its money and not care how bad off anyone else was.

Beauty and ugliness side by side. On the surface the gated community is beautiful but it is an artificial beauty and Jason soon realises this. What is noteworthy is in the the very next story in the book, ‘The Scratchboard Project’ which I quoted from earlier, Jason finally discovers true beauty.

The word ‘beauty’ never appears in this book, not once, but ‘beautiful’ does, fourteen times; six times in the first story, talking about the landscape surrounding the town, and eight times in this one referencing not only the girl Shanice’s physical beauty, but also her inner beauty, despite living in the poorest part of town and being physically scarred.

The thing I found about this book is that even though it’s doesn’t romanticise the past—as Bradbury might be accused of doing—and Jason is not blind to the ugliness that pervades his life and the life of those around him, it’s still—and this is important—his ugliness. It’s not attractive but it is familiar and there is a comfort to be had in that.

A tourist town must be an odd place to grow up in because you get to witness people looking at things you’ve grown up with and grown tired of and unable to see anything more than the attractions, not recognising the truth of life for the residents. In an article John writes:

People come to the historic tourist town of Harpers Ferry, West Virginia … to look the demon abolitionist John Brown in the face. They come to pay honour to the pioneering spirits who make up the town’s black history, like W.E.B Du Bois and Frederick Douglass. Some even come for the flat-out ghost action in this mini Salem, Massachusetts, civil war style, just an hour’s drive from Washington, D.C.

[…]

But for those of us who grew up in the theatre of these paranormal claims, we snicker at the nonsense. We guffaw and scoff. We rattle penny-filled soda cans out our bedroom windows and wail, “Ooooh, I’m a ghost. Hey, up here.” Ghosts? Please. How about having a real-life father who stalks you and slaps the back of your head? Now there’s a phantom to fear. How about a dear old dad who rants for hours about how his sons are nothing but trouble? Not there’s a banshee with high blood pressure. Or how about growing up feeling ashamed and inadequate in the face of girls because of the abuse? Now there’s an emasculating poltergeist in your heart for life.

[…]

While there is triumph in these interlinked stories and there is growth, the monster is not imaginary, and there’s no old man in the woods to give young Jason supernatural powers, no magical sword for him to draw from the ground, nothing but full-legged, towering adults to make growing up terrifyingly real.

This is an excellent collection, I have to say, and the stories are very much to my taste in their approach to storytelling; they are not neat; they ask more questions than they answer. In an interview John talks about his first experiences of being published but of more interest is his approach to writing:

I tried to make my language flourish in a more organic spontaneous way, yet highly stylised. They were more like vignettes, meditations, and stream of consciousness writing. A jumble of ideas, descriptions, emotions captured in an unravelling string, well polished and well delivered. There is a beauty in literary journals, who are so defiant of mainstream. Eclectic is a famous word for journals, that’s what is so wonderful about them, they keep more with the way reality is, it doesn’t wrap things up like a book.

I’m happy to recommend this collection. I don’t like to lumber it with the YA tag though. I don’t think it’s necessary or helpful. True, the stories are not the most demanding you’ll ever read but neither are they trite. They don’t try and do the reader’s job for him and because some younger readers might not be able to bring as much to the table as an adult reader might they might not pick up on some of the book’s subtleties. Not in a single reading anyway. There was a lot I missed the first time and I’m a grown man.

Yes, Ugly to Start With is a book, so John’s stories can literally be wrapped up in a book but this particular book doesn’t wrap anything up. We don’t know for sure if Jason gets to go to art college in Worsh-ington (as his father insists on calling it) but it looks like he will. Whether he he will escape is another matter.

You can download a PDF of the opening story to the collection, ‘The World Around Us’, from the publisher’s website here but there are a number of other stories from John available online which will give you a taste of his approach to storytelling:

From Ugly to Start With

Other Stories set in Harpers Ferry

A few more stories

***

John Michael Cummings was born in 1963 in Harpers Ferry. His short stories have appeared in more than seventy-five literary journals, including North American Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, The Chattahoochee Review, The Kenyon Review, and The Iowa Review. Twice he has been nominated for The Pushcart Prize. His short story ‘The Scratchboard Project’ received an honourable mention in The Best American Short Stories 2007. His debut novel, The Night I Freed John Brown, was the 2009 winner of The Paterson Prize for Books for Young People (Grades 7-12) and one of ten books recommended by USA Today for Black History Month. Originally a newspaper reporter John now lives in Orlando, Florida with his cat Sentry where, for a while, he taught writing classes but now he tells me he’s “just a poor writer and student this semester” currently working on his third book which will serve as his thesis for his master’s degree.

John Michael Cummings was born in 1963 in Harpers Ferry. His short stories have appeared in more than seventy-five literary journals, including North American Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, The Chattahoochee Review, The Kenyon Review, and The Iowa Review. Twice he has been nominated for The Pushcart Prize. His short story ‘The Scratchboard Project’ received an honourable mention in The Best American Short Stories 2007. His debut novel, The Night I Freed John Brown, was the 2009 winner of The Paterson Prize for Books for Young People (Grades 7-12) and one of ten books recommended by USA Today for Black History Month. Originally a newspaper reporter John now lives in Orlando, Florida with his cat Sentry where, for a while, he taught writing classes but now he tells me he’s “just a poor writer and student this semester” currently working on his third book which will serve as his thesis for his master’s degree.