“Good old-fashioned police work, Bob,” Collison said with heavily overdone enthusiasm. “Nothing like it.” – Ash Larton, A Killer in Profile

I’ve read virtually no crime fiction apart from William McIlvanney’s Laidlaw trilogy and then only because McIlvanney wrote them; had he written a spy novel and an office romance I’d’ve read them, too. I have, however, watched (depending on how you think about these things) a laudable or lamentable amount of crime shows on television from Dixon of Dock Green on: shows featuring grizzled detectives; novices; cowboys and buddies; DS’s, DCI.’s, DI’s, DC’s and plain ol’ Policemen Plods; FBI’s; CSI’s; CIA’s; CID’s; Flying Squads and cold case squads; hardboiled PI’s; quirky consultants; judges and lawyers who don’t know their place; medical examiners, forensic pathologists and anthropologists; profilers; criminal psychologists; dead detectives (Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) in case you couldn’t think of one); old-fashioned coppers; olde time coppers; good cops and bad cops; timecops, Psi Cops, future cops and android cops; dark knight detectives and amateur sleuths of every ilk; I’ve watched programmes from the UK, the States, Canada and any other country I could lay my hands on—Sweden (Wallander, Sebastian Bergman and Crimes of Passion), Belgium (Salamander), Denmark (The Killing), Norway (Varg Veum), France (Spiral and Braquo), Australia (Underbelly and Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries), New Zealand (Harry), Italy (Inspector Montalbano) and that’s just what I can remember off the top of my head—so, frankly, it takes a lot, an AWFUL LOT, to impress me these days. I really don’t watch programmes like Castle and Vera to see them solve crimes; I’m far more entertained by the interactions of the characters. The shows I enjoy the most are those with the more interesting casts, shows like The Bridge, Cracker, Wire in the Blood and the lamentably short-lived Jeff Goldbum vehicle Raines. So when I was asked to review Ash Larton’s debut crime novel A Killer in Profile (bit of an old-fashioned title there) you can just imagine how I felt. I was prepared not to like it. Frankly, I expected to hate it. I imagined it’d be littered with all of my favourite (I’m being sarcastic here) tropes. How could he possibly avoid them?

Charlie Brooker—who created the spoof crime show A Touch of Cloth—has this to say about his source material: “There are weird things that happen in any programme that don't happen in real life. They all have to do certain things. They're genre pieces: you accept when you watch that they're going to have that format.” And Larton says something similar in his novel: “Storylines from fiction always seem inherently improbable to occur in real life, yet when we read them we are happy to suspend our disbelief, which may simply suggest that in our everyday lives we have an irrational craving for certainty and probability.” His novel isn’t a parody or even a pastiche but it is clearly self-aware. Question: After decades of books, magazines, comics, films and television series covering every aspect of crime investigation is it possible nowadays to commit any crime that doesn’t have its fictional antecedent? At one point in A Killer in Profile one of the characters notes, “You’re working on the assumption that there’s nothing new in crime and thus at one time or other, someone must have written about exactly such a situation.” And that is what proves to be the case. Only if it was as simple as that then there’d be classes in Ruth Rendell, P.D. James and Colin Dexter at the Police Academy and Quantico.

A Killer in Profile opens with the discovery of a body. It’s a classic opener so why mess with the classics? The only thing that’s slightly quirky is that the corpse is discovered by Boyo, a border collie, whose owner is lying in a drunken stupor in the next street. The woman appears to be the fifth victim of a criminal the police (at least among themselves) have dubbed “the condom killer”:

“Morning, Bob,” [Tom Allen] said as Detective Inspector Metcalfe saw him coming, and walked towards him. “What have we got?”

It was a private joke between them that they often resorted to clichés from old police films and television shows. A couple of years previously, a drug dealer whom they had pursued through the streets of Brixton had been surprised, as he lay prone on the pavement being cuffed, to hear Allen say, “Book him, Danno”, at which Metcalfe had lent over him and said, in a passable imitation of John Thaw in The Sweeney, “Right, sunshine, you’re nicked.”

“SOCO thinks it’s the same guy,” Metcalfe replied, “but of course they won’t commit to anything until they get the body back to the lab and do their stuff. Single head wound, no knickers, and he’s pretty sure there are chloroform burns around the mouth.”

So what kind of crime novel is A Killer in Profile? Most fall into two categories: whodunits and howcatchems. Occasionally, whydunits like the first Laidlaw. Agatha Christie wrote classic whodunits ending in a dénouement in a drawing room if  available; the format’s certainly not dead, that’s how most Death in Paradise episodes end. We always knew who the criminal was when watching Columbo and we enjoyed watching him toy with his prey. This book treads a fine line between the two although the revelation at the end is different; I’ll grant Larton that. It certainly feels like your bog standard police procedural at the start and for the most part it remains on course. Until the detective in charge is persuaded to bring in a profiler. The DS is well aware that a “profile is not evidence, just a guideline which may make our task a little easier” and “[g]ood old fashioned police work” is what’s going to solve the case but eventually is forced to admit: once “[w]e had our nice new shiny profile … it seduced us into not looking too far outside it.” In shows like Criminal Minds the profile is everything and in some cases (e.g. Sam Waters in Profiler and Frank Black in Millennium) profilers are presented as virtual mystics. The reality—which is what I believe Larton is trying to get us to acknowledge—is nowhere near as clean-cut or as trustworthy. I say this because after about a third of the book a man who fits the profile to a tee is identified, arrested, charged, convicted and imprisoned and you just know they’ve got it wrong. Well, of course they’ve got it wrong. But who’s to say when they look at the evidence with fresh eyes that they’ll get it right a second time?

available; the format’s certainly not dead, that’s how most Death in Paradise episodes end. We always knew who the criminal was when watching Columbo and we enjoyed watching him toy with his prey. This book treads a fine line between the two although the revelation at the end is different; I’ll grant Larton that. It certainly feels like your bog standard police procedural at the start and for the most part it remains on course. Until the detective in charge is persuaded to bring in a profiler. The DS is well aware that a “profile is not evidence, just a guideline which may make our task a little easier” and “[g]ood old fashioned police work” is what’s going to solve the case but eventually is forced to admit: once “[w]e had our nice new shiny profile … it seduced us into not looking too far outside it.” In shows like Criminal Minds the profile is everything and in some cases (e.g. Sam Waters in Profiler and Frank Black in Millennium) profilers are presented as virtual mystics. The reality—which is what I believe Larton is trying to get us to acknowledge—is nowhere near as clean-cut or as trustworthy. I say this because after about a third of the book a man who fits the profile to a tee is identified, arrested, charged, convicted and imprisoned and you just know they’ve got it wrong. Well, of course they’ve got it wrong. But who’s to say when they look at the evidence with fresh eyes that they’ll get it right a second time?

And the same goes for forensic evidence. From the book:

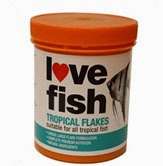

“They have identified the yellow powder that was found at our last crime scene.” He stopped for effect and looked at the piece of paper in his hand. “It’s fish food. But not just any old fish food like they sell in supermarkets or pet shops. This is very special food for tropical fish, and it’s only sold by a few specialist outlets. The only one around here is in Hendon Central.

Not just any old fish food, eh? How many times does this happen in a TV show? TV Tropes refer to this as GPS Evidence:

So your investigation seems to have hit a dead end. Either you have no prints, or you stumbled across a Red Herring, either way the situation seems hopeless...

But wait! The guys at the lab have found the clue you were looking for! Turns out some of the trace in the crime scene is a rare plant that can only be found in a certain part of your town! Or sand that comes from a specific island where one of the suspects have visited recently! Either way, now you're certain where to go. The Lab Rats have stumbled across GPS Evidence.

GPS Evidence is able to pinpoint a certain geographical location with amazing accuracy. It points straight to either the location the heroes are trying to find, or the person they are seeking (if said person was the only person who visited the place that the evidence pinpoints).

I groaned when I read about the fish food. And I was meant to. Too easy! I did exactly what the cops did. I made an assumption. And we all know what happens when you assume: it makes an ass out of you and me. Do you imagine criminals don’t watch TV shows too? I’m not going to explain. That would spoil it. But just as a dog not barking is both proof and not proof (depending on what the question is) so is the existence of a few grains of fish food. This is scene from the book:

I groaned when I read about the fish food. And I was meant to. Too easy! I did exactly what the cops did. I made an assumption. And we all know what happens when you assume: it makes an ass out of you and me. Do you imagine criminals don’t watch TV shows too? I’m not going to explain. That would spoil it. But just as a dog not barking is both proof and not proof (depending on what the question is) so is the existence of a few grains of fish food. This is scene from the book:

“Oh, yes,” said Williams with a positive twinkle in his eye. “There is indeed. Take a look at this.” He held up a sealed plastic laboratory packet, which at first glance seemed to be empty. “If you look very carefully, you will observe a few grains of fine, sandy-coloured powder. I found them while rummaging through our victim’s pubic hair.”

“From the killer?” Metcalfe’s eyes lit up.

“I would think it’s highly likely, wouldn’t you?”

If the culprit can get a few grains of sandy-coloured powder into his underpants what’s to stop the victim getting a few grains of sandy-coloured powder into her knickers? No one asks that question. They assume. And they’re wrong. But because the guy they arrest, the guy who ticks all (okay, most) of the boxes listed down the side of their profile has a fish tank then he’s got to be the killer. Makes perfect sense.

Here’s the scene in the book where we get to hear Dr Collins begin to present his profile of “the condom killer”. I’ve edited out all the cross-chatter:

“First and foremost, our killer is most probably a loner. He either lives alone, or has a job which involves him spending a lot of time on his own, possibly travelling.

“I’m having problems categorising him. The serial killer’s motivation usually falls into one of two broad groups: punishment or fantasy friendship. In the first case, the killer believes that women are evil and deserve to be punished. Sometimes this feeling is limited to prostitutes, but in more extreme cases it can extend to all women. Killers of this type can exhibit religious mania, even to the point of claiming to hear God telling them what to do. Yet in everyday life they can behave quite normally.

“Killers in the second category often kill almost for company, literally so if they live alone and keep the body for an extended period, as though it were a sort of houseguest. In this case we may be talking about having sex with the body after death, and constructing some sort of fantasy relationship with it. This element of fantasy may play itself out in the rest of their lives too, perhaps pretending to have had some sort of dramatic and impressive past, or knowing famous people, or having fantasy friends and sexual partners.

“[T]o a certain extent we have elements of both types. The killings appear to be the result of random sightings, which argues for the first type, as does the fact that they were all young women on their own, who either were or could be taken by a disturbed personality to be prostitutes. But that’s about as far as it goes. In particular, these killings are quite clinical. Punishment killers usually indulge in frenzied attacks with multiple injuries, and often mutilation of the body as well. There’s none of that here.

“The two things which exercised me a good deal were the manner of killing and the use of a condom. It seems to me, on reflection, that taken together they may tell us quite a lot.

“First, the victims have all been struck over the head by a heavy instrument, which may be a hammer. He either rapes them first and then kills them, or the other way round, we’re not sure which. An initial hammer attack argues for a desire to make absolutely sure that the victim is incapacitated straightaway with a single blow. Whether before or after, it shows a desire to get things over with quickly and cleanly.

“What can we make of the hammer blow? Our man is uncertain of his ability to overpower a woman quickly and effectively. Therefore he is likely to be of slight build and below average height. He certainly will not have any background of hard physical work, nor come from the armed services (though he may well brag about some fantasy military background) nor be proficient in any physical activity which involves in some way imposing yourself on someone else—rugby, say, or martial arts. In short, our man is a bit of a weed.”

All perfectly reasonable. Only after having finished the book and heard a detailed explanation by the murderer of how the crimes were committed; where and why, do you realise how wrong he gets everything. And, to my reading, it all stems from a single initial assumption. But, of course, I’m not going to tell you what it was.

When you pick up one of Ian Rankin’s early novels with their Rolling Stones inspired titles you know you’re going to get the less than immaculate John Rebus with his fondness for whisky and a tendency to make up the rules as he goes along and if you pick up a Ngaio Marsh you expect to see an Oxford-educated gentleman detective with a fondness for actresses (at least in the early novels). The point is you know what you’re getting. What might you expect when you pick up an Ash Larton? Well, that’s the problem. We begin with Detective Chief Inspector Tom Allen, “a good old-fashioned copper who believes in gut instincts”. He’s been on the case for eighteen months and made little progress because there’ve simply been no viable leads. Surprisingly he’s replaced within the first few pages by Simon Collison who’s best described in this interchange with the assistant chief constable:

When you pick up one of Ian Rankin’s early novels with their Rolling Stones inspired titles you know you’re going to get the less than immaculate John Rebus with his fondness for whisky and a tendency to make up the rules as he goes along and if you pick up a Ngaio Marsh you expect to see an Oxford-educated gentleman detective with a fondness for actresses (at least in the early novels). The point is you know what you’re getting. What might you expect when you pick up an Ash Larton? Well, that’s the problem. We begin with Detective Chief Inspector Tom Allen, “a good old-fashioned copper who believes in gut instincts”. He’s been on the case for eighteen months and made little progress because there’ve simply been no viable leads. Surprisingly he’s replaced within the first few pages by Simon Collison who’s best described in this interchange with the assistant chief constable:

“You’re an intelligent man, Simon,” the ACC said slowly. “Your academic record shows that. But have you ever considered that perhaps you may be approaching this too intelligently?”

“I’m not sure I understand you, sir. How can a police officer, or indeed anyone, be too intelligent?”

“Perhaps I’m expressing myself badly,” the ACC said, fiddling with his reading glasses. “‘Intelligent’ may be the wrong word. ‘Rational’ might be better.” He broke off and put the glasses down on his desk on top of the report. “The best detectives I’ve worked with in my career were bright, too, even though they didn’t have your sort of formal education. But they had something else; they had instinct, some sort of subjective awareness that came to them, apparently from nowhere.”

“Copper’s nose, sir?”

“Yes,” the ACC said flatly.

So like Inspector Lynley or even more like DI Joseph Chandler from Whitechapel but without the OCD. Allen in the meantime determines to carry on his own investigation. And we’ve seen that plenty of times too: the rogue cop (shades of Rebus there). So who’s going to be the focus now? Well for a while I actually thought it was going to be Detective Inspector Metcalfe, Allen’s second who is caught between his loyalty for his former boss (and friend) and the new guvnor, plus we have the budding office romance between Metcalf and the leggy Karen Willis to distract us:

The picture was only a head and shoulders shot and had not prepared the doctor for the effect of Karen Willis’ legs, which not only temporarily deprived him of the power of intelligible speech but also brought the bright chatter inside the café to a halt as male customers stared unashamedly and female customers glared at their male companions.

Then we have the consultant and many of the more watchable TV shows are based around an oddball character like Daniel Pierce (in Perception) or Charlie Eppes (in Numb3rs). And this seemed especially likely when Peter Collins goes… let’s just go with off the rails… after his profile results in a huge cockup and he takes on the persona of a famous fictional detective. (No, not Sherlock Holmes. And not Poirot. And absolutely not Precious Ramotswe. Don’t press me.) But then he fades into the background too. So what we have here is an ensemble cast with no charismatic lead but that’s not really an issue because the story drifts from one character to the next seamlessly and efficiently like handing over a baton in a relay.

At its heart this novel has more in common with the writers from the Golden Age of detective fiction. Everybody’s so jolly decent I don’t think they even swear. A far cry from the grisly work of, say, Val McDermid or Karin Slaughter. The publisher’s website says, “A Killer In Profile is also reminiscent of popular television detective  dramas such as Midsomer Murders and Inspector Morse” and they’re right except for the fact that Morse and Barnaby are stronger characters than Collison but as this is to be the first of an ongoing series of “Hampstead Murders” perhaps he’ll develop into a bigger and more interesting character over time. It’s a minor criticism though.

dramas such as Midsomer Murders and Inspector Morse” and they’re right except for the fact that Morse and Barnaby are stronger characters than Collison but as this is to be the first of an ongoing series of “Hampstead Murders” perhaps he’ll develop into a bigger and more interesting character over time. It’s a minor criticism though.

The novel’s overall tone is a little uneven as if it can’t quite decide what it wants to be but I suspect that’s a deliberate attempt to keep the readers’ guessing; at least he doesn’t change direction halfway through and fill the Freemason’s Arms with a small army of vampires. That said the chapters where Dr Collins starts playacting although delightful are unexpected because up until then we’ve been reading what we thought was a by-the-numbers murder mystery with not a lot of humour and then this. There’s also the question of the next books. Could Larton pull this off a second time? I have my doubts but would be happy to be proved wrong. Edward Buchan, in Whitechapel, was introduced originally as a ripperologist but his role was expanded and his character fleshed out in later series.

The reveal was a bit of a disappointment because even though the killer appears, as they tend to do, early on in the book and is dismissed as a suspect, I’m not sure many (if any) will deduce the killer’s true identity because, and this is something Christie was very guilty of, a key piece of information—usually someone is not who we thought they were—is withheld until the last moment. I wasn’t disappointed for long because then we got to learn the hows, the wheres and the whys and just how easy it could be to take the evidence the police had at the start and misinterpret it so; although there’s a lot of good solid policing done, the team’s surprisingly incompetent at times too:

“Whatever the case,” Collison said ruefully, “there’s not a lot we can do about it. It’s not as though he’s a suspect, after all.”

“Excuse me, guv,” Priya Desai said suddenly, “but why not?”

There was total silence as everyone in the room turned to look at her. She looked embarrassed, but determined.

“Explain,” Collison asked simply.

“Look at the board, sir.” She walked to the front of the room and pointed. “You wrote these words yourself. We think our killer is an opportunist who has a vehicle in which he can carry his murder kit. Well, a taxi is a vehicle. A taxi driver meets a lot of lone women, especially at night, and we know that a taxi driver was the last person to see our fifth victim alive.”

Collison stared at her. So did Metcalfe. So did everybody.

“God in heaven, why am I such an idiot?” Collison cried.

Just because you see something in a TV crime show doesn’t mean it’s accurate. People get shot, stabbed and knocked over the head and they literally just lie down and die; they don’t writhe in pain for ten minutes unless there’s a need for an ongoing dialogue. I watched a guy get smothered on The Blacklist a while back. It took about twenty seconds whereas the reality is you’d probably need to keep pressing on that pillow for a good five minutes to be sure. I mention this because, again, one of the assumptions everyone makes is really based on what they’ve seen on TV and it’s only when it’s pointed out to them—which seems to be the role of Priya Desai on the team—that they take a step back and go, “Oh!”

These reservations and observations aside, what do I think? It kept my interest and that in itself is an achievement. Its strength lies in the fact it knows its audience. No one will pick this book up without having watched more cop shows than they probably realise and they’ll expect (unconsciously perhaps) the book to be formulaic (which it is for the most part) and it uses that to its advantage. For a first crack at the whip, what can I say? Well done.

***

A while ago there was a bit of a kerfuffle in the press over a debut crime novel by a certain Robert Galbraith who turned out to be no other than a certain J.K. Rowling. I can’t tell you much about Ash Larton other than the fact that’s not his real name and he is also an award-winning and best-selling author of both fictional and factual works. I’ve read (and enjoyed) three of his previous novels and once you know a bit about him and his reading habits it’s easy to see him in this book; it’s not quite the radical departure I’d been expecting and I’m rather glad of that because he’s played to his strengths.

A while ago there was a bit of a kerfuffle in the press over a debut crime novel by a certain Robert Galbraith who turned out to be no other than a certain J.K. Rowling. I can’t tell you much about Ash Larton other than the fact that’s not his real name and he is also an award-winning and best-selling author of both fictional and factual works. I’ve read (and enjoyed) three of his previous novels and once you know a bit about him and his reading habits it’s easy to see him in this book; it’s not quite the radical departure I’d been expecting and I’m rather glad of that because he’s played to his strengths.