Death was a whore; she always chose the fragile ones. – Novel Without a Name

Vietnam. It's a word I grew up with. There was a war there. For some reason it was an unpopular war. That's about as much as I knew about the place when I was a kid. I suppose if Britain had been sending troops over there that might have been different. I do remember thinking that it was a bit soon after the Second World War to have another war but I supposed the grownups knew what they were doing.

As I grew up film and TV programmes started appearing revolving around the Vietnam War. The Viet Cong were the bad guys. They didn't wear black hats but everyone knew they were the bad guys. Their speciality was psychological warfare, sneaking into camps and cutting up tents while the soldiers were sleeping, that sort of stuff. At least that's what I was led to believe but I've not been able to find much to substantiate that position and the Wikipedia articles on the Viet Cong's battle tactics seems quite thorough.

Suffice to say in the movies and TV programmes all they were there for was to be shot in exactly the same way as the Nazis were in World War II. It must be a war thing, depersonalise the enemy, strip him of his life, his family and his beliefs and reduce him to a mindless, faceless killing machine. I imagine many people thought that about the North Vietnamese in the sixties and seventies. I bet most people didn't even know why they were all called 'Charlie' ('Charlie' was short for the phonetic representation 'Victor Charlie' for 'VC', Viet Cong.)

I consider that, though, the war that most people have been heralding, the war against the Americans, is in fact the most stupid war in our history. And it created a war where brothers became enemies and Vietnamese became a Kotex in between the two forces of two trains colliding. Our people are a tampon of a race.

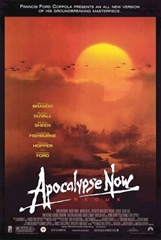

I became aware of Novel Without a Name when it was first published in the UK in 1995. The title intrigued me – it is a great title – but the cover put me off; I've never been into war books. And so it passed me by. If I'd even read the blurb on the back I might have reconsidered because it's not just another book about Vietnam, it's a book written by one of those 'Charlies' on the other side, actually a 'Charlotte' if we're going to be accurate:

Dương Thu Hương [pronounced zung tu hung] was twenty-one when she led a Communist Youth Brigade to the most heavily bombarded front of Vietnam's 'War Against the Americans'. She spent the next seven years there, living in tunnels and underground shelters alongside the North Vietnamese troops. Of her volunteer group of forty, she was one of three survivors. – from the front page of the Picador edition

Now that did pique my interest. I had no idea there were women on the front lines. She was actually a theatrical performer whose job it was to boost the soldiers' morale.

As it happens though the hero of Hương's book is a male, Quan, a company commander. Hương's approach to her novel is an interesting one because the first thing she does with her hero is take him away from the battlefront. When, in 1965 (which is when American marines and soldiers began to be deployed), Quan joined up he was accompanied by two childhood friends, Luong and Bien. When they marched away together all they could think about was honour and glory but now, ten years on, we find three quite different characters: Luong has moved up the ranks and is now Quan's commander – he has become the complete embodiment of the Communist soldier; Quan is tired, sick and disillusioned, however, he is a loyal soldier and a fair chief who is well-liked and respected by his men; Bien it seems has gone mad.

At the start of the book Luong summons Quan and reassigns him:

"I want you to go find out what's happening with Bien. I've written a letter to Nguyen Van Hao, the division commander, and another to Doan Trong Liet, the political officer. You'll see what the story is when you get there. Do whatever you think is necessary. After you've settled this, use the opportunity to take some leave."

On the surface this sounds like Luong is doing Quan a great favour but reading in-between the lines I'm not entirely convinced his motives are all that pure. Quan presses Luong:

"The war . . . It's going to be a long time, isn't it?"

Luong didn't answer. I pleaded with him: "It's just you and me. Tell me."

Luong stood without moving or speaking for a few minutes. Then he turned and walked away. I followed him, and we plunged into the forest. The air smelled of rotting leaves, and it grew more and more humid. The night engulfed us, broken only by the sudden, aimless cries of birds. I still wanted to call out to him, to put my arm around his shoulder. But I held back. Time had slipped between us; we were no longer little boys, naked and equal.

Quan is the narrator of the book but in addition to his recording what happens to him over the next few weeks we also get to hear his recollections of his childhood as well as a few disturbing dreams when he can grab a few minutes sleep. This is not so much a book about war, it is a book about people who happen to be at war and who have been at war far longer than they ever expected.

As he travels he thinks. And for much of that time he thinks about food. Food is a major issue mainly because there is very little of it to go around. In addition to fighting a war the soldiers also have to scavenge for food in the jungle or hunt wild animals. Orangutan has recently become a favourite of the men:

The memory of the boiling-hot soup we had eaten at the foot of Mount Carambola came back to me. The soldiers had squatted down in a circle, banging their spoons against their mess tins, their eyes riveted on the steaming pot. Every now and then the cook stirred the clear broth with its floating grains of puffy cooked rice . . . and tiny orangutan paws . . . like the hands of babies.

[…]

Everyone had congratulated one another. I just stared at the tiny hands spinning in circles on the surface of the soup. We had descended from the apes. The horror of it.

Quan's is not an easy journey. At one point he gets lost in, what he learns later has been called by another troop of soldiers, The Valley of the Seven Innocents, an ocean of green colocassias and khop trees where he nearly dies of starvation. The term 'khop' is not explained in the book. It turns out it refers to broad-leaf tropical forests but a few footnotes would have been helpful here and there not simply to explain the different kinds of vegetation that are mentioned but also some of the titles. Many times Quan is referred to as bo doi by the civilians he meets but it's never explained. Bo means 'foot' and doi means 'unit' or 'group' so the western equivalent would most likely be 'foot soldier' and yet when the term is used it feels like there is a respectful tone, a similar kind of tone to the one you would use when talking to or about a sensei master. By the way he is treated being a soldier – any kind of soldier – is something deserving of respect.

This is where the book got interesting for me. We get to know the Vietnamese people, the ordinary folk in the villages, the ordinary men who have volunteered to fight for what they're told to believe in. Marxism might have been the official driving force but there is another side to these people. The word 'comrade' is used but not nearly as often as 'uncle' or 'elder brother' where there is no immediate familial connection. The Vietnamese in this book come across as one big – and despite their hardships – happy family.

Late in the book, as he is making his way back to the front, Quan stops a supply convoy looking for a lift. The driver in the lead truck nearly knocks him down in fact:

"Are you crazy?"

The driver jumped out of the truck. "We don't have any brakes left! Just a bit farther and you would have gone to hell and sent me to a court-martial!"

I laughed awkwardly.

"Sorry, elder brother, you understand . . ."

He grumbled. "Come on, get in."

I said nothing and climbed into the truck. After a moment he turned toward me and asked, "What’s your name?"

"Quan."

"My name is Vu. Twenty-five years old. Hung Khoi village. And you? You must be about thirty?"

"Only twenty-eight. The white hair, that's from the sorrow of life. Dong Tien village."

"Ha, ha – your district is right next to mine. We're from the same province. So, shall we swear to eternal brotherhood in the peach garden? Our little club already has about twenty-three members, and that's just in my division. You want to sign up?"

You see what I mean? Quan doesn't refer to Vu by rank or the title 'Comrade', no, but rather, in a gesture designed to pour oil on troubled waters he calls him "elder brother" and you see within minutes Vu wants to reinforce than bond of kinship. Rulers come and rulers go but the people stay essentially the same.

As I said, after some difficulties Quan finds his way to the camp where Bien is being held. His madness is nothing new. For six years now the man has been locked in a small cell surrounded by piles of his own excrement. He's not crazy – Quan recognises that immediately – but he doesn't let on and returns later on his own, instructs him to follow him down to the river where Bien cleans himself up and they discuss his options. Quan is willing to arrange for him to be discharged "on grounds of psychological instability" which would enable Bien to return home and settle down but he refuses:

I fell silent. I understood. A cock will fight to death over a single crowing. We had both been mobilised the same day. Luong was already a commander, a staff officer. Despite my impossible temperament, I had been a captain for three years now. Bien was still a sergeant. Now, with a mental illness on top of it all, he didn't have a prayer of leaving the front and returning to the village with any honour. The rumours would be awful. No doubt, somewhere in his young peasant's heart he still dreamed of glory. He couldn't let go of the struggle. Bien would rather hide in some godforsaken hole, in this immense battlefield until V-day – until he could march with the rest of us under the triumphal arch.

Since he can't discharge Bien Quan arranges for him to be "sent to Huc's unit, M.0335. They're in charge of special missions." At the time he's unaware about what so special about their missions but later on he finds himself there; sees Bien settled in, happy and active and finds out just what they've been tasked with, the construction of coffins which the Huc's men actually sleep in at night for protection from the wind and the fog. A macabre image if even I heard about one. Quan is provided his own coffin for the duration of his visit.

When Quan arrives in his home village we get to see the effect of the war on a section of the general populace. His father, once a soldier himself in the war against the French, has grown old and feeble; his life has completely lost direction. Quan arrives home to find him eating in the dark:

"Father? Are you having dinner?" I asked.

He turned toward me and was silent for a moment before he spoke: "Is that you, Quan? You're back."

"Yes, I just got here." My voice seemed to echo through the house. "Why don't you have a light on?"

"What for? A few silkworm grubs and soup? It's not worth attracting the mosquitoes."

To top this off he discovers that his younger brother, a brilliant scholar who had been coerced into enlisting by their father, has been killed in action and his girlfriend, Hoa, who had promised to wait for him, on hearing nothing for years, had finally joined up herself. It transpires that she has now become pregnant and has been discharged from the forces but because she refused to divulge the name of the father she has been disowned by her parents and is now living alone in a shack on the outskirts of the town. War is part of everyday life. No one's life has failed to be touched by it.

Reading through this book several times I was reminded of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four in particular when Quan overhears two party officials having an unguarded conversation about how their own love for the Marxist revolution is beginning to fade. The line that jumped out at me is something "the short one" says:

"Words are like everything else in life: They're born, they live, they age, they die."

All of a sudden we hear:

"Attention!" … A military officer wearing a red armband stood in front of the two men. He spoke carefully, weighing each of his words: "We have a report that you just insulted Karl Marx, our venerable leader, that you slandered our socialist government."

The men are outraged and "the little fat man" hands the officer a diplomatic passport:

"It's we who are in charge of introducing Marxist thought to Vietnam. We are the ones who teach the people – to which you belong – just what Marxist ideology is all about. When it comes to defending Marxist thought, that's our business, not yours. Is that clear?"

This so reminded me of O'Brien's conversations with Winston Smith. O'Brien is under no delusions about the party he is in and yet he still toes the party line. These two are clearly tarred with the same brush. It feels a little contrived having Quan get the train so that he can overhear their chatter but it works. How else was Hương going to cover all her bases because you'd never see these two in Quan's normal daily life? I think she can be forgiven.

This is not the first time Quan has become aware of the duplicity of those in charge though. When fighting in southern Vietnam his troop engage in a confused night-time battle in which the enemy unit they attack turns out to be one of their own. The authorities never acknowledge the error and later Quan is horrified to read a report that describes the encounter as a "glorious victory" by revolutionary forces. No one could be unaffected by news like that.

The style of this book is very simple but it is an effective way of covering a lot of areas in a believable way. There is no real plot. Quan ends his journey where it began. We have no idea if he is going to die or survive the war although it does seem likely considering the fact the war ended on April 30, 1975. It doesn't really matter through.

What I didn't like were the many dream excerpts we get treated to. I'm not a fan of dream sequences at the best of times but I didn't think these added greatly to the book. Most are short and so they don’t take anything much away either but I would rather have seen a few less of them.

Novel Without a Name is not a great book – it's certainly not great literature – but despite it's flaws I think it is an important book. It humanises the Vietnamese – there's not a single 'Charlie' in the whole thing and actually only one American, a journalist from all accounts and not a soldier. Killing takes place off the page. Even the tiger attack is something we learn about after the fact. Hương doesn't try and cover everything in this one book. She sets out her stall and sells what she has to sell, one man's experience of the war and its effects on those close to him; this is a novel not a history book. Quan has seen so many of his comrades die. There are only twelve veterans left at the end of the book, all the rest are rookies; his brother has died but he has also lost his girlfriend, his father and his friend Luong in the worst kind of ways.

"Yeah, glory only lasts so long."

"What happens afterward?"

"How do I know? We're all in the same herd of sheep."

***

The first time she saw prisoners of war, she realised that they had black hair and olive skin like her: They were also Vietnamese. She realised that this was not a war against invaders, but a war between differing philosophies. “It was so new, I didn’t dare think it through to the end. That was the beginning of the mental itinerary that led me to change my views,” she relates. – World People's Blog, 11th Aug 2006

A vocal advocate of human rights and democratic political reform, Hương published short stories and novels about hunger and malnutrition in Vietnam, but her books were banned and she was expelled from the Communist Party in 1989. In 1991, after sending abroad a manuscript of Novel Without a Name she was imprisoned in solitary confinement for seven months without trial. International pressure from the P.E.N. Writers Association and Amnesty International helped obtain her release. That same year, she was awarded the Prix Femina and the UNESCO Literature Prize.

Dương Thu Hương lived and wrote in Hanoi under permanent surveillance for many years and was not allowed to travel abroad. This relaxed over time and after two foreign trips she finally relocated to Paris in 2006. In January 2009, her latest novel, Đỉnh Cao Chói Lọi, was published; it was also translated into French as Au zénith.

***

Further Reading

Steven P. Liparulo, “Incense and Ashes”: The Postmodern Work of Refutation in Three Vietnam War Novels

16 comments:

Got to read her for using "kotex"!

Shame she chose to use a male protagonist when her own story is so unusual and powerful.

Another beautiful review here, Jim and in this one you tell us the full story.

It is a moving story and although you say it's not a great novel I agree it's one that needs to be told.

War stories have long troubled me, especially those related to the Vietnam War. In Australia conscripts were selected on the basis of their birth year and whether their number on a marble was selected from a barrel. What a lottery. My husband just missed out.

If he had been selected he would have been a conscientious objector I suspect. In any case his life would have been turned upside down.

Thanks Jim. You have honoured this work and the memory of the Vietnam war with your balanced and thoughtful review.

I felt much the same, Rachel. Perhaps in her other books she uses a female protagonist. Or maybe she thought that since there were more males having a man as the main character would present a more realistic novel. I don’t know. There is one female soldier in the book but I think there's only the one.

And, Elisabeth, even though I wouldn’t call it a great novel it is an important book. I’m getting old enough now that I can see a pattern in my own lifetime of how blinkered people are during a time of war: the only good [insert racial stereotype here] is a dead [insert racial stereotype here].

The first time this really hit me was when the Falklands War started here and suddenly guys I worked with were all expressing the passionate desire to put on khaki and head off to kill Argentineans. There was a bloodlust in their eyes that actually scared me. That may seem a strong expression and perhaps it is an exaggeration but that is how I remember it (remember how untrustworthy memory is). I saw them all calling me an “Argie-loving bastard, carrying me up to the roof and chucking me off.” Talk about mob mentality. A week before none of them even knew where the Falklands were. We all thought they were up around Shetland.

Man has lost the capacity to foresee and to forestall. He will end by destroying the earth. - Albert Schweitzer

I was just as confused as you, Jim about the Vietnam War - still am.

I never knew where Charlie came from. Makes sense.

A couple of my boyfriends in the sixties went to Viet Nam and were changed forever. One I still correspond with on Facebook seems to have worked through his PTSD - finally.

Very interesting review.

I'm not normally a war novel reader but this sounds like an interesting story. I would like her perspective on a nonsensical war.

ann

The Vietnam War was the first war I was ever aware of, Kass. I can’t say I thought about it much. I don’t even recall it being talked about much. I do remember thinking somewhere along the line that it was pretty soon after World War II to start another war. Had we not learned our lessons then? The itinerant Vietnam vet was a recurring character in films as I grew up and that was another thing I never got, how come these heroes weren’t appreciated more in a country that holds up heroism as an ideal above many others?

And, Ann, no, I’m the same but it was the fact that it was a novel from the other side of the war that interested me. I may not have read anything much about the Vietnam War from the American perspective but I’ve seen all the big films about it and was glad for the opportunity to have an alternative view.

Riveting stuff again, Jim, and a set of vivid reminders of the impact of that war on Western culture.

The Vietnam War has become a sort of paradigm for insane hubristic adventurism everywhere. Grab them by the balls and their hearts and minds will follow. It took 30 years for Western democracy to realise that the cultural subjugation of Vietnam wasn't working out so well. That in actual fact it was generating increasingly fierce and resolute resistance year on year. How long will it take in Afghanistan?

That’s where I see history repeating itself, Dick, the screwed-up vets in all the TV shows are men and women who’ve fought in Iraq or Afghanistan. I’m just waiting on Oliver Stone doing Born on the Ninth of November.

My memories of that particular war seem mainly linked to the protest songs coming out of America, which for some reason did nothing to undermine the fact of the North Vietnamese - the Vietcong, actually - being the bad guys.

Years later I had a group of Vietnamese boat children in my school - and suddenly the war was distant in neither time nor space, but as real as the one I had actually lived through.

It was a while before I got the protest songs, Dave. I was a bit young at the time. But in much the same way as I was puzzled why we needed to have another war so soon after the Second World War I was also puzzled why people were objecting to it. If your government decides that a war needs to be fought then a war must surely need to be fought. That’s why we elect governments, to make difficult decisions like that. It’s really only in recent years that I’ve begun to appreciate just how wrong governments can be and not just foreign government who just need us to put them straight but our own parliamentary representatives, blokes like you and me who thought it might be nice to be in charge for a bit and then realised that they weren’t quite up to the job but kept straight faces and hoped no one would notice.

I like novels of this genre. It makes me come back to life, to reality.. It makes me think deep about life.

Thanks for the feedback, blog about drugs. Yes, it is strange how a novel like this might be described as ‘life affirming’ and yet it is. You see it in the tales of the little people in the book who have been continually stomped on by their own government and yet they just keep going and hoping when they have so little to keep them going and all they can truly hope for is an end to the hostilities.

Oddly, I'm an American and I also grew up knowing little about Vietnam but its name and that it was bad.

But WWII? OMG!!! Nothing but knowing how bad that crazy Hitler was! Kind of makes you think doesn't it?

Wars are seen in the eyes of the aggressor, or, in our case, not seen, and not talked about to the young. Just an observation. I'm just saying.

What gets me, Evelyn, is that there are people who are going round saying that the Holocaust never happened. Okay, there’s hardly a soldier left who fought in World War I and within not that many years there will be no one left who fought in World War II but I would have thought with the invention of the camera that we’d never ever get to a he-said-she-said situation again. Maybe I’m wrong. My own feeling is that there is simply too much information available so that nothing, not news, not art, not anything is processed properly before the next new and interesting thing comes along to distract us. And, of course, of all the topics out there History is the only one that just needs to sit there: every day we have one more day of history to learn about and one less day left to learn about it in.

I'm from north VN. My grandfather fought in the American War (just as you call it Vietnam War.) There were millions of young men and women died in this war, and in the end, the VNmese goverment didn't and still don't do the job they're supposed to do. It's all lies, war is stupid.

To me, Duong Thu Huong is also a humanitarian because of her honesty in describing truthfully the human pains.

Thank you for that comment, nước Mỹ của tôi. I think this is an important book. I’ve grown up with one side of the story. It was good to see how things were on the other side.

Post a Comment