Arsénie Negovan, property-owner, is seventy-seven years old. It is the 3rd of June 1968 and he has not stepped outside his front door since the 27th of March 1941. For the past twenty-seven years he has run his business empire with the aid of his wife, Katarina, and the family lawyer, Mr Golovan, while he sits at his window peering at his women through a selection of binoculars: Simonida, Theodora, Emilia, Christina, Juliana, Sophia, Eugénie, Natalia, Barbara, Anastasia, Angelina . . . and those he could not see though his lenses he could picture in his mind’s eye. To each and every one he had been devoted and had been for many, many years. His wife knows all about them. How could she not? He has photos of them on the wall of his study. And scale models even!

The ‘women’ are, of course, houses, the things Arsénie Negovan prizes over everything else. Says Arsénie:

Houses are like people: you can’t foresee what they’ll offer until you’ve tried them out, got into their souls and under their skins.

Many people are property owners. Property is generally considered to be a sound investment. But financial gain is not what drives Arsénie. He has a “completely original angle” on property which he has managed to distil down to a number of axioms, the top four of which (the only four he can remember) are:

1. I do not own houses; we, I and my houses, own each other mutually.

2. Other houses do not exist for me; they begin to exist for me when they become mine.

3. I take houses only when they take me; I appropriate them only when I am appropriated; I possess them only when I am possessed by them.

4. Between me and my possessions a relationship of reciprocal ownership operates; we are two sides of one being; the being of possession.

Freud said it was sex; Jung, belonging; Viktor Frankl, meaning and Adler, power. In one of his essays, however, Pekić singled out “the will to possess” as one of the most powerful driving forces in our world, a phenomenon which inevitably influences even the “spiritual and moral side of man.”[1]

Although he was responsible for the construction of some houses – always houses intended for residential occupation, Arsénie had no interest in business properties or offices – his real joy came in discovering some new building, desiring and then acquiring “her”. Borislav Pekić’s novel The Houses of Belgrade (which was originally published under the title The Pilgrimage of Arsenije Njegovan and is the first in a

Niké was the secret name I gave to the house as soon as we fell in love.

He begins visiting Stefan more and more often:

Indeed, during my ever more frequent visits to Stefan all that happened between myself and his house can hardly be described in any other way than adultery, and since it all took place under cover of the host’s innocent hospitality, adultery in the most shameful of circumstances. ... Our romantic meetings in the street can also be counted here, for in the course of my business walks, which I continued according to the schedule in my saffian notebook, I used to pass her every day at a predetermined time. On these occasions quite brazenly, almost leaning out over her luxurious conservatories and balconies, she would give herself up to my wondering gaze, and her face, intent on keeping our sinful secret, would let slip those four clear Corinthian tears which I could only interpret as unsatisfied desire for me.

It is not love at first sight however. Oh, no. Far from it. His first opinion is that the building is a “monstrosity” and he is as obsessed with having it pulled down as he later becomes in owning it. But acquiring the house is not as easy as making an offer to his cousin. After much effort on Arsénie’s part Stefan does agree to put the house up for auction and this is where Arsénie is headed on the 27th of March 1941 when things go wrong for him and he ends up surrounded by a mob protesting against the assumption of power by General Simović.

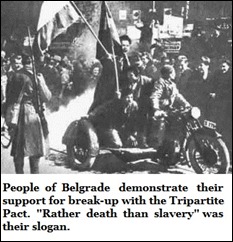

| A bit of history: On March 25th 1941 in Vienna, Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, signed the Tripartite Pact. On March 27th the regime was overthrown by a military coup d'état and the 17-year-old King Peter II of Yugoslavia seized power. General Simović was appointed prime minister. On the morning of 27th March, first in Belgrade and then in other cities, people took to the streets. They rose the slogans "Rather war than the pact", "Rather death than slavery", "We demand a pact with the Soviet Union, not with Germany", etc. This put the new government in an awkward position since they wanted to keep good relations with Germany. Several hours after the coup d'état, in the morning of 27th March, the new Yugoslav foreign minister, Momčilo Ninčić, assured the German envoy in Belgrade that Yugoslavia would continue a friendly policy towards Germany, and on 5th April he proposed direct talks with the German government. The talks, however, never happened. Adolf Hitler correctly surmised that the British were behind the coup against Prince Paul and vowed to invade the country. The German bombing of Belgrade began on 6th April 1941. In the early hours of 13th April the 8th Panzer Division drove into Belgrade, occupied the centre of the city, and hoisted the Swastika flag. |

This is one of the most interesting sections of the book because here Arsénie begins interrogating himself to get to the truth he feels is buried in this memory. And

Some time earlier Arsénie had “been asked to give a lecture at the Jubilee of the Circle of the Sisters of Serbia ... under the general title ‘The Different Faces of Belgrade,’ which was to take place ... in the large hall of the Kolarac Institute B.P..” During this he proposed to expound upon the “benefits of the equal, reciprocal dual-phase type” of ownership. He does not, however, get the opportunity to explain his “philosophy of Possession”; after presenting his outline to one of the initiators of the function, Joakim Teodorović, Teodorović himself steps in and delivers the lecture in his stead; Arsénie is not even permitted to attend as a guest.

So, what happens when he inadvertently manages to attract the mob’s attention? He delivers his speech verbatim there and then amid cheers and derisory remark and ends up being beaten up for his trouble. Needless to say he does not make the auction and Niké becomes another man’s.

Twenty-seven years pass. Arsénie becomes a recluse. He loses interest in the outside world, with the sole exception of his houses. He even stops listening to the radio or reading the papers. At first he and his wife receive a steady stream of visitors and guests but, little by little, put off by Arsénie’s disinterest in current events, these dry up. Occasionally he overhears a bit of news and is under the delusion that he still has his finger on the pulse but the simple fact is that he hasn’t a clue what’s happening in the world. What then could possibly induce him to go outside after all this time?

You’ve guessed. A ‘woman’.

He has learned that “the lovely Greek Simonida with her fine, dark countenance, her milky complexion beneath deep blue eyelids, and her full-blooded lips pierced by a bronze chain, African style” is going to be knocked down. “It was with Simonida that [he] began to give the houses names. First just ordinary ones, then personal ones.”

I always chose feminine names. I didn’t do this because, in our language, the words house, block, palace, villa, residence, even log cabin, hut, shack, are all of feminine gender, whereas building, country-house, and flat are masculine, but rather because I couldn’t have entertained towards them any tenderness, not to mention lover’s intimacy, if by any chance they had borne coarse masculine names.

Arsénie determines to visit her one last time and put a stop to demolition but as soon as he steps out of the door he steps into his past. Memories, beginning with the October Revolution, carry him down this street and then that. In his mind he is once again swept away with the mob and then, in what depending on how charitable you feel is either a contrivance on the author’s part or one heck of a coincidence, Arsénie this time finds himself caught up in the student riots of 1968.

| Another bit of history: The 1968 Yugoslavian student riots began on the night of June 2nd with a clash between the students and the police in Studentski Grad, a student district in the capital of Belgrade. A popular theatre company were booked to play the university but there were not enough tickets. The students requested that they perform at the university's large open-air amphitheatre but instead authorities arranged for them to play a smaller venue and only make seats available to youth members of the ruling Communist party. On the night of the show, a large group of students gathered outside the theatre and attempted to force their way in. The police intervened with guns, and the situation escalated into a street battle. This was just the catalyst. Due to the country’s economic and social reforms unemployment was high, particularly amongst graduates, many of whom had to wait one or two years for a job; |

This time Arsénie does not get to give any speech but he does lose his hat, a Boer, which he risks life and limb to retrieve:

[I]t was a question of principle: That hat was mine; it belonged to me by inalienable right of ownership. One might say that all revolutions began with hats, with the destruction of the outward signs of dignity.

Battered and bruised he survives this second encounter, makes his way home and writes his will “on the back of tax forms and rent receipts,” whatever comes to hand. In fact it is his will we have been reading up until this point, certainly, if it was a real will, one of the longest one could imagine. In between the recollections and the misremembering – like his buildings his mind is also crumbling – we have his various bequests not all of which can ever be met because Arsénie no longer has a true picture of his world let alone the world at large; he no longer possesses some of the items he wishes to bequeath and not all of the beneficiaries are alive to learn of their good fortune.

The book ends with a two-page Postscriptum in which Pekić explains how he came in possession of the manuscript and his relationship to Arsénie Negovan. These last two pages are quite illuminating and provide a rather sad coda to a most unusual life.

The novel was not well received by the government when it was first published and Pekić was accused of being a supporter of the students although he did not share their radical Marxist ideology in the least. (All they had to do was read the book to know that.) Consequently, when he decided to leave Yugoslavia and move to England in 1970, he was refused a passport and had to wait for a year before he could join his wife and daughter abroad. The

Arsénie Negovan is self-centred, obsessed and cantankerous, but there is something appealing about him too; we Brits have a fondness for eccentrics. Through his eyes we get a unique take on Yugoslavian history and through the metaphor of the gradual decline of a builder's mind, Pekić allows us to examine the nature of identity, alienation and the fear of loss. Houses become people and it’s easy to see how a man who had been locked up for five years with only a Bible to read could write the following:

For just as people who have done nothing at all wrong are got rid of simply because they stand in the way of something, so houses too are destroyed because they impede somebody's view, stand in the way of some future square, hamper the development of a street, or traffic, or of some new building.

Of course Arsénie’s logic is back to front but his point is valid nevertheless.

It took me a little while to get into the book but once I did it flows nicely. The only things that really bothered me were the fact that there are no chapter breaks (I like my books chopped up into chunks) and Arsénie has a habit whenever “excited or in a difficult position” of lapsing into French and my French is not very good.

You can read an excerpt here and see a scanned copy of most of it, c/o Google Books, here.

***

In 1953 he began studying experimental psychology at the University of Belgrade Faculty of Philosophy, although he never earned a degree.1958 marked the year of his marriage to Ljiljana Glišić, an architect and the niece of Dr Milan Stojadinović, Prime Minister of Yugoslavia and the publication of his first of over twenty film scripts, among which The Fourteenth Day represented Yugoslavia at the 1961 Cannes Film Festival. This success did however not soften the official ban issued by the ruling Communist Regime on the publication of any of Pekić's literary works. His first book, Time of Miracles, was only published in 1965 many years after the manuscript had been completed.

In 1985 he was elected to the Serbian Academy of Science and Arts and was made a member of the Advisory Committee to The Royal Crown. Posthumously, in 1992, Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia awarded him the Royal Order of the Two-headed White Eagle, being the highest honour bestowed by a Serbian monarch.

FURTHER READING

‘Crowd Ask Arms’, New York Times, 27th March 1941. This is a transcription. You can view the scanned original here.

Želimir Žilnik, ‘Yugoslavia: “Down With The Red Bourgeoisie!”’, German Historical Institute, Washington DC, Bulletin Supplement 6 (2009), pp.181-187

Z. Antic, ‘Yugoslav Youth Insist on Further Reforms and Democratization’, Radio Free Europe Research

Jelena Milojković-Djurić, Borislav Pekić’s Literary Oeuvre: A Legacy Upheld

REFERENCES

[1] Bogdan Rakić, Borislav Pekić: Sysiphus as Hero

This is an expanded version of the review that originally appeared on Canongate’s site.

12 comments:

.. a fascinating post beautifully composed.

Lovely post, I so well know the feelings re houses!

Thank you, Helen, it was a fascinating read.

And, Von, yes, I've always loved architecture too. My wife bought me a copy of The Sims when it first came out - my one and only computer game - but I spent more time designing buildings than I did playing with the wee people.

I read that with some difficulty as my computer was hijacked a few times by an anti-wikileaks website.

I have always been of the Jungian persuasion, myself, but this book rather tends to convert me towards Freud. If your last book had a touch of navel-gazing (as was suggested, though not by me) this seems to be of the same ilk. I'm not wholly against that - in moderation.

In spite of all - perhaps in part because of - I am fascinated by what you write. Definitely on my possibles list!!!

You know, Dave, I’ve been using that expression for years without actually knowing where it originated. So I looked it up:

In the mid-19th century the word Omphalopsychic, the name of a religious sect whose members achieved a trance state by gazing at the navels, was translated into ordinary English as navel-contemplators. From this the term navel-contemplation for complacent self-absorption, or a narrow view of things, came into use. By the early 20th century, this had been simplified to our modern navel gazing.

I have to say I have no problems with introspective writers. In many respects it cuts to the chase. We want to know what’s going on inside other people’s heads and third person narratives really don’t cut it even if they are easier to write. I didn’t think I was going to enjoy this book but once I got into it I got quite caught up in his world. A shame all the history went whoosh over my head but that’s where writing these reviews is so great because I don’t just put the book to the side when I’m finished with it and miss half the point.

I have a love affair with houses too, but not to the extent Negovan does. I am quite particular and know right away if the home is my type. I have a tablet of old-fashioned tickets that my father somehow got hold of and I'm often tempted to go around giving tickets of violation to the owners of houses who distort and maim them.

Interesting review.

I have mixed feelings when it comes to houses, Kass. I like to look at nice buildings but since I spend most of my time inside them their functionality is really paramount. I like to be in a space that feels comfortable. I can work pretty much anywhere when I have to but the more control I can exercise on that space the more I like it. My office is like a comfort blanket. I don’t spend so much time in it these days but knowing it’s there makes all the difference. The outside of our flat pleases me or rather doesn’t displease me but I have no control over it and I’m not so petty that I would have turned down the flat just because the shell didn’t suit me. As things go I left buying the flat completely in Carrie’s capable hands and I never even saw inside it until we’d actually bought the thing: I only had two preconditions, 1) that we both could have our own office and 2) no garden. As both were met I was quite happy.

Introspection is a balancing act: it's all too easy to fall down into that wishing well and not be able to climb out again. The idea is to balance on the lip of the well, looking in, but also able to leave the well and go for a walk.

Jung wrote of his various psychological types to emphasize that integration of all the different functions was the goal: not to become ever more introspective or extraverted, but to find the dynamic balance point where one could be either at need. Integration, not extremism. A lot of navel-gazing literature is problematic because of its extreme introversion, its lack of balanced integration, or so it seems to me.

In other words, some writers really do need to get out more. Granted they might be perfectly speaking for or reflecting their times and social conditions, and this is probably particularly so for those generations of writers living under oppressive political regimes. But even granting that, I don't find claustrophobia OR agoraphobia particularly interesting in fiction anymore. Probably that's just my problem, my perspective, my fault.

It's so much easier to write fiction about dysfunction, because of course dysfunction evinces easy, obvious conflict. What I'd really like to see someday is a novel about full functional, fully self-actualized people, the kind of people Maslow rather than Freud wrote about. I suppose most writers would find that a dull read, though. Frankl was about finding meaning in life, and was an influence on Maslow and the transpersonals. How about a literature of finding meaning, rather than finding dysfunction? Would anyone but me read that?

Freud was indeed fascinated by sex, the energy of it, and its place in our lives. I don't think Jung has anything to do with this novel, though, except that he might characterize it as an example of obsessive introversion. The house is an archetype, but in this book it seems more of the shadow archetype than the actualized one. Possession, in Jungian terms, technically means that one has become possessed by one's shadow, one's unconscious, and one's own unrealized, unexamined archetypal self.

I love architecture, too. If I were 20 years old right now, I might seriously consider studying it as a profession. I am mostly interested in the styles of architecture that can be considered very old, very primal, or very new, very clean-lined and plain.

I find most European house architecture to be typically either overdecorated or plainly ugly; sorry about that. The interior spaces were obviously more important than the facades on the street in many cases; except of course where overdecoration is a status indicator. I do like the natural materials and clean lines of Scandinavian and other far northern styles.

Perhaps for similar reasons I feel a lot of very introspective fiction to be overdecorated. I'd rather read Beckett than most novels such as this one. Or Virginia Woolf. It's quite possible to be introspective without being dank and musty, or tangled up in Gordian knots.

As interesting as your review makes it—and kudos to your reviews—it's unlikely I'd ever read a novel like this. I get it, I really do, about wanting to be inside someone else's head, to experience life through their viewpoint—which is one thing the novel is all about as a literary form. But I find I prefer houses with lots of big windows letting in lots of light, and I prefer novels the same way.

Of course the protagonist here is dysfunctional, Art, but it’s a horrible term. He functions as much as he wants to. It’s society that says he’s not a fully functioning member of itself and labels him ‘dysfunctional’; he simply prefers to see things a little differently to everyone else. He’s like an alien who helps us see who we really are by providing an outsider’s perspective and we love characters like Mork or Data for that. They’re not dysfunctional, they simply function differently. People who prefer their own company are in danger of being labelled schizoid when the simple fact is they have a higher tolerance for solitude than most people so much so that being alone is actually beneficial. I agree with you though, dysfunction is a good way to introduce conflict into a story, the classic example being the dysfunctional family, and there will be those who would argue that without a conflict there is no story.

I wanted to be a draughtsman when I left school and actually got a job in an architect’s office for a while. I’m rather sad that AutoCAD wasn’t around back then or I might have stuck with it but even though I was top of my year in Engineering Drawing (98%) I wasn’t prepared for the workplace and I blame the school system for that. We should have been working with pens right from the start. The simple fact I was neither fast enough nor accurate enough to do the job and if I hadn’t resigned I would have been sacked. I would have loved to have a crack at designing buildings. I’m a lot like you, I don’t like over decoration. I like straight lines. Not obsessed about windows though. I like looking in other people’s but that’s about it for me.

A fascinating post, Jim, about an amazing book and character, Njegovan.

It makes me think about the stuff of possessiveness and 'collecting' and the ways in which we might try to take possession of our memories or of history or of our world views, when we cannot.

Thanks, Jim.

What came to my mind here was actually transference, Lis, Negovan now devotes all his attentions to his property and has lost all interest in people. I’ve always thought much of the pleasure in collecting comes from not having a full set because what do you do when you do? The real pleasure is in attaining as opposed to maintaining. Collections in this respect can consist of single items, a wife for example, which is why some marriages fail because once you’ve ‘collected’ you wife what do you do with her then? Negovan hasn’t continued acquiring properties and so, although that may well have been what drove him at the start, that’s not what has kept him going for the twenty-seven years he’s been holed up in his house. The thing is he’s not really interested in his property either, just the idea of his property. It’s as if he’s discovered Sim City and it perfectly happy playing at being a property-owner rather than having to worry about actually being one.

Jim,

I've just been back for another read of your post.

I read it through more rapidly (probably) than last time, and I've come away with a different feeling about the book. It began with the axioms. They seemed to make more sense (in my terms) than last time, and the whole thing rolled on from there. An interesting experience.

Post a Comment