[S]atire is always at its best when it’s local and immediate. – Česlon Keenlowski[1]

Gogol’s play The Government Inspector follows the exploits of Khlestakov, a penniless government clerk who is mistaken for a powerful government inspector in a small provincial town. When David Farr sat down to adapt Gogol’s play he transformed Khlestakov into Martin Remington Gammon, a failed British real estate agent headed to a fictional Eastern-bloc country. When Jim Sherman’s turn came he Americanised the script: Londoner Martin Gammon had now become Michael Fitzgerald Murphy, a loser real estate agent from Chicago's South Side. The reason is as stated by Keenlowski above which is why Elisabeth Weis wrote:

When George S. Kaufman proclaimed that "satire is what closes on Saturday night," he was referring to its ephemeral quality: satire dates quickly. I would add that political satire dates twice as quickly. Probably because the painful realities it mocks are all too immediate, political satire seems particularly funny while it is fresh. But the intensity of satiric humour is often inversely proportional to its durability. Try looking at the opening monologue from last year's Tonight Show. We don't even get the jokes. Or look at any reruns of Saturday Night Live that bash then-current presidents. For every political satire that remains funny, there are a dozen that could be called Saturday Night Dead.[2]

Gogol was a political satirist and yet his work has stood the test of time. Why? Because what he was satirising was not unique to the time in which he lived. His more mature writing attacked the corrupt bureaucracy of the Russian Empire, leading to his exile. Corrupt and incompetent bureaucracies pepper the history books which is why, with a few name changes, the essence of The Government Inspector can so easily be transferred to a contemporary setting. Parodists from the likes of Monty Python to Mel Brooks have long pillaged his works for plots and gags.

The Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov was also a big fan and the influence of Gogol can be clearly seen especially in the early works that make up the short story collection, Diaboliad, and Other Stories, which was first published in 1924 and has recently been reissued in a new translation by Hugh Aplin. This new collection contains the novelette, Diaboliad, along with three stories:

- No. 13 – The Elpit Workers’ Commune

- A Chinese Tale

- The Adventures of Chichikov

Does a writer choose his subject matter or is he chosen by it? It’s a good question. In a radio interview the 2009 Nobel Prize winner, Herta Müller, had this to say:

I have no other landscape other than the one I know, the one I came from. [My] literary characters reflect what happens to the human being in a totalitarian society or system. And I believe this is not a topic that I chose, but rather one that my life has chosen for me. I don't have that freedom of choice. I cannot say: 'I want to write about that thing, or about that other thing.' I am bound to write about what concerns me and about the things that won't leave me in peace.[3]

Bulgakov could have said much the same. He was born into a Russia that was undergoing seismic changes. The bedrock of their society was about to shatter and all hell was about to break loose. I mean that metaphorically. Bulgakov imagined it literally and his most well known work is his novel The Master and Margarita. It is an immensely popular book. My own review of it has been read by about a thousand people and counting.

Diaboliad

The historical events that Bulgakov experienced firsthand seem to have instilled in him a sense of powerlessness. In Bulgakov's work, his heroes are often fearful of the forces of violence and chaos, represented by mob rule, rampant ignorance, petty bureaucracy or a ruler's tyranny and there is no better example of this than in the novelette Diaboliad in which the modest and unassuming office clerk Korotkov is summarily sacked for a trifling error from his job at the First Central Depot for the Materials for Matches, and, when he tries to get his hands on the man to blame for his dismissal, he is sucked into a nightmarish vortex of Soviet bureaucracy. The mess he ends up in begins innocently enough. He takes a report to his boss, the depot manager, Chekushin, only to find his way obstructed by an odd little man:

This stranger was so short that he only came up as far as the tall Korotkov’s waist. The lack of height found compensation in the extreme breadth of the stranger’s shoulders. His square trunk sat on crooked legs, and the left one, moreover, was lame. But most noteworthy of all was his head. It constituted an exact, gigantic model of an egg, set horizontally on the neck and with the pointed end at the front. It was a bald egg too, and so shiny that electric bulbs glowed on the stranger’s crown without ever going out. The stranger’s tiny face had been shaved until it was blue, and his green eyes, as small as pinheads, sat in deep hollows.

The following scene is highly reminiscent of the writing of Lewis Carroll; indeed the little man would have been quite at home in Wonderland. The stranger says to him:

‘Do you see what’s written on the door?’

Korotkov looked at the door and saw the long-familiar sign: “Report before entering.”

“And I do have a report,” said Korotkov foolishly, indicating his document.

The bald man unexpectedly grew angry. His little eyes flashed with yellow sparks.

“You, Comrade,” he said, deafening Korotkov with the noise of saucepans, “are so backward that you don’t understand the meaning of the simplest office signs. I’m truly amazed at how you’ve remained in work until now. … Give it here.”

With that he snatches the document from Korotkov, scribbles a note on it with an indelible pencil, and tells him: “Be off!” Korotkov subsequently discovers that Chekushin has been replaced but he never learns his new boss’s name before he feels he has to take action on the note written on his memo which, inexplicably, read:

All typists and women generally will in due course be issued soldiers’ uniform drawers.

Korotkov sends a telegram to the manager of the supply subsection and busies himself in his office until home time.

Of course that’s not what the note said. Korotkov has mistaken his new boss's name Kalsoner for the word kal'sony (underwear). In Aplin’s translation he renders the bald man’s name Drawitz which Korotkov has misread as ‘drawers’ because of the fact he has signed him name with a small d. He comes into work in the morning to find a sheet of paper nailed to the general office wall advising everyone that he is being dismissed with immediate effect.

Opening door after door of this immense beehive, reminiscent of the Lito building in Notes on the Cuff, he is confronted alternately with scenes of absurdity (a middle-aged woman weighing an evil-smelling fish) and loss of individual identity (six identical typists).[4]

Needless to say he can’t find the office and has to return on another day before he finally locates it. Of course when he finally is seen all the fair-haired man wants to know is:

“Keep in brief, Comrade. All in one go. In a trice. Poltava or Irkutsk?”

Irkutsk is in Siberia, Poltava, in the Ukraine.

Needless to say he gets nowhere with the man who ends up flying off (literally!) after reminding him that:

“The Thirteenth Commandment says: thou shalt not enter thy neighbour’s office without reporting.”

Things do not end well for Korotkov, let’s put it that way. Once he loses his personal documents he effectively loses his identity. As Bulgakov writes in The Master and Margarita: "Without documents, a person does not exist.” The story then descends into chaos. The final chapter is actually entitled: ‘A Knockabout Cinema Chase and the Abyss.’ It reminded me a bit of the end of Blazing Saddles which always felt like to me that Brookes had run out of direction on his script and thought, What the hell, let’s just finish with a good old-fashioned chase.

I had an overwhelming feeling reading this novelette – been there, done that – but the simple fact is that this book came before, well before all the things like the film Brazil that this reminded me of. The expression Kafkaesque gets chucked around quite a bit but I think in many instances he should share the honours with Bulgakov. Mind you Bulgakovian is a bit of a mouthful.

Diaboliad had been used as a title before Bulgakov. The satirist William Combe wrote a poem by that name in 1677.

No. 13 – The Elpit Workers’ Commune

‘No. 13 – The Elpit Workers’ Commune’ opens with a description:

It used to be thus. Every evening, the mousey-grey five-storey hulk’s hundred and seventy windows lit up the asphalted courtyard and the stone girl by the fountain. And the green-faced, mute, naked girl with a pitcher on her shoulder gazed languorously at herself all summer in a round and fathomless mirror. And in winter a wreath of snow lay on her fluffed-up stone hair. On the gigantic, smooth semicircle by the entrance doors gurgled and shuddered each evening, and sweet little lamps shone on the tips of the shafts of smart horse-drawn cabs. Ah, what a famous building it was. The splendid Elpit building…

The fashionable Elpit-Rabkommun House, the subject of ‘No. 13 – The Elpit Workers’ Commune’ is actually destroyed twice and provides a perfect metaphor for what Bulgakov believed communism was doing to his country. First, it is appropriated by the state and converted into a workers' commune. Then, falling victim to the ignorance of its uncultured residents, the building burns to the ground. This is not the only time that Bulgakov uses a building in this way:

In her discussion of ‘The Khan's Fire’(1924), Haber detects a distinct pessimism in Bulgakov's account of Prince Tugai-Beg, who returns to his ancestral estate only to find this once-living storehouse of five generations of family history has become a museum – as Haber says, "the common property of the new Soviet man." Enraged by what Haber calls the "perversion of the original significance of the house," the prince sets fire to the structure, which is by now only the empty shell of the culture it once represented.[5]

At least in ‘The Khan's Fire’ the prince’s estate is still intact. The Elpit-Rabkommun House has been handed over to the temnye liudi (ignorant or "dark" people), who do not appreciate the symbolic importance of the place. The piano music that once

And the prince pranced, and the sparks dashed down the black pipe and flew off into the enigmatic jaws… And then into the black bends of the narrow, felt-lined ventilation shaft… And into the loft…

The prince becomes “a fiery king,” a “demon … fanned the flames … [a]nd now it really is hell. Pure hell … a sprawling, hot, orange beast” fills the sky” but not all is lost. There is one guest at least who has escaped with a little something of the past:

With a samovar in one arm and in the other a quiet, white old man Serafim of Sarov, in a silver riza.

Two symbols of traditional Russian culture and domestic ritual – a samovar and a religious icon. The narrator says:

It was a glorious time … And then there was nothing. Sic transit gloria mundi! It's terrible to live, when kingdoms are falling.

Social transformation cannot simply be achieved by a change of name. The “dark” people have to find their way to the light, the light being enlightenment, what Russians would call prosveshchenie. Interestingly Prosveshchenie was a legal Bolshevik monthly sociopolitical and literary journal published in St. Petersburg from December 1911 through June 1914. A total of 27 issues were published, with the circulation of some issues reaching 5,000. It’s interesting to compare the uses of light and dark imagery in this text.

A Chinese Tale

I’m not going to say much about this one. It is a story about a stranded Chinaman, Sen-Zin-Po, who joins the Red Army. I’m not sure I would have included it in this collection, not that it’s not a decent story but there are so many other stories by Bulgakov that focus on the hellish society that Russia had become. This one is really about the cruelty and absurdity of civil war. It’s clever the way the story is presented, as the subtitle to the piece says, “Six scenes in place of a story.” Also the coolie is presented as a comic stereotype and no one would get away with a story like this these days. That said, if you can get beyond the politically incorrect dialogue there’s some nice writing in this one and it’s probably the most accessible of the four pieces.

The Adventures of Chichikov

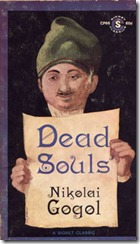

The premise of Gogol’s Dead Souls is a simple enough one, as Wikipedia puts it:

The government would tax the landowners on a regular basis, with the assessment based on how many serfs (or "souls") the landowner had on their records at the time of the collection. These records were determined by census, but censuses in this period were infrequent, far more so than the tax collection, so landowners would often find themselves in the position of paying taxes on serfs that were no longer living, yet were registered on the census to them, thus they were paying on "dead souls." It is these dead souls, manifested as property, that Chichikov seeks to purchase from people in the villages he visits; he merely tells the prospective sellers that he has a use for them, and that the sellers would be better off anyway, since selling them would relieve the present owners of a needless tax burden.

[…]

Chichikov's macabre mission to acquire "dead souls" is actually just another complicated scheme to inflate his social standing (essentially a 19th century Russian version of the ever popular "get rich quick" scheme). He hopes to collect the legal ownership rights to dead serfs as a way of inflating his apparent wealth and power. Once he acquires enough dead souls, he will retire to a large farm and take out an enormous loan against them, finally acquiring the great wealth he desires.

In 1841 the first part of Dead Souls was ready so Gogol took it to Russia to supervise its printing. It appeared in Moscow in 1842 under the title imposed by the censor: The Adventures of Chichikov which Bulgakov used as the title for his short story although it is, like Dead Souls, described as a poem.

What it is is a dream where Gogol's poshlost’ from Dead Souls returns to 1920s Moscow only to discover that his cynical schemes have become more the norm than the exception.

Poshlost' is the Russian version of banality, with a characteristic national flavouring of metaphysics and high morality, and a peculiar conjunction of the sexual and the spiritual. This one word encompasses triviality, vulgarity, sexual promiscuity, and a lack of spirituality. The war against poshlost' is a cultural obsession of the Russian and Soviet intelligentsia from the 1860s to 1960s.[7]

There is no English equivalent. He usually gets called a hero-villain or something of that ilk.

Chichikov finds that all his old cronies are still there. As he puts it:

Wherever you spit one of you is sitting.

This is a much harsher story that ‘No. 13 – The Elpit Workers’ Commune’ which, although it acknowledges the faults of the past, focuses more on its positive aspects. This presents a darker picture of the New Economic Policy than is common in Bulgakov’s work from this period when he was associated with the Berlin-based Russian paper Nakanune. In another work from this period, ‘Moscow of the Twenties’ he cries out: “We must finish building Moscow! … Moscow! I see in you skyscrapers” but there’s none of that here.

Much of the enjoyment of this story is dependent on knowing who Chichikov is. Taking a character out of one time and placing him in another to provide objective commentary is not new – the satirical TV series Adam Adamant Lives comes to mind – but the real point here is how well Chichikov fits in and adapts; it’s as if nothing has changed. This wasn’t the first time that the character of Chichikov had been borrowed by another writer either: some years later “[Nikolay]Andreyev wrote an amusing serial modelled on Gogol’s Dead Souls with Gogol’s hero Chichikov appearing as a Russian émigré and a Displaced Person.”[8]

What is clear about Chichikov in Bulgakov’s story is that he knows how to work the system. He witnesses one of his own, a man after his own heart, Sobakevich, claiming for an academic ration he is not due, so what does Chichikov do?

No sooner had Chichikov seen the way Sobakevich was handling rations than he fixed himself up too. But, of course, he surpassed even Sobakevich. He got rations for himself, for his non-existent wife and child, for Selifan, for Petrushka [characters from Dead Souls], for the uncle he had told Betrischev about, and for his old mother, who was no longer alive. And academic ones for them all. And so they began delivering food to him by lorry.

And having thus settled the question of nutrition, he set off to other government offices to get jobs.

By ‘jobs’ he means that he looks for opportunities to swindle people:

Chichikov’s career thereafter assumed a dizzying character. What he got up to beggars belief.

He fills in forms, gets loans, signs contracts, “issued counterfeit notes to the value of eighteen billion” which he mixed up with genuine ones “and exchanged his billions for diamonds in order to flee abroad.” He is discovered by a man “who had never even held Gogol in his hands, but [who] did possess a small dose of common sense.”

***

This in an interesting collection which I am happy to recommend with a couple of provisos: read The Master and Margarita and, if possible, Dead Souls first. Dead Souls isn’t especially long and you can even read it online here; its value for money is also a consideration. I said at the beginning that satire works best when its local and current and that’s the problem with this collection; it’s now eighty-five years old and the Russia that he was talking about is long gone and so a lot of the wit that satire depends on will miss you even though the translator has done his best to make sure we get the joke. A joke that has to be explained is never funny though. When Sen-Zin-Po says, “Get-bone-arse pay me, pay me,” that’s still funny – the little boy inside me went, “He said, ‘Arse,’” – but why naming a character Henrietta Potapovna Firsymphens should be funny at the time I have no idea, even after reading the notes: Buggerov I did get though.

[1] Gogol Sets the Stage for Satire on a Global Scale

[2] Elisabeth Weis, ‘M*A*S*H Notes’, Play It Again, Sam: Retakes on Remakes, p.311

[3] Herta Müller, from a transcript of a 1999 radio interview for Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty's Romania-Moldova Service

[4] Edythe C. Haber, Mikhail Bulgakov: the Early Years, p.180

[5] Biography of Mikhail Bulgakov presented by Amy Singleton Adams, College of the Holy Cross, p.9

[6] Edythe C. Haber, Mikhail Bulgakov: the Early Years, p.157

[7] Svetlana Boym, Common Places: Mythologies of Everyday Life in Russia, p.41

[8] Nikolay Efremovich Andreyev, A Moth on the Fence, p.250

5 comments:

You have me worried. You've reminded me of how avidly I used to lap up satire, and now I almost never do. Is it me that has changed, or the satire, I wonder. Maybe these stories are what I need to refresh my palate. I did enjoy poshlost as a word for vanity.

I wonder if it’s an age thing, Dave? I used to enjoy satire more when I was young but nowadays I don’t find it quite so funny. I know it’s simply a means of getting across a serious message but there are a lot of issues that we have to face where the phrase “this is not a joking matter” seems more appropriate. If something can be laughed at then surely it’s not that serious. There’s also something a bit impotent about satire. It’s like we can’t do anything about the problem so we might at least try to gain some comfort from the situation by joking about it. It’s something to do when there’s nothing to do. I know this is an oversimplification but it’s a thought.

I still enjoy good satire(or at least I’m going to say I do so I don’t have to admit to being old). These stories sound like an interesting, change of pace read. Thanks for the stimulating review.

I have to agree with you and Dave, Jim--your post reminded me of how I lived on satire in my college days and always thought that would be my favorite read.

Nowadays, I like my satire light, ala Terry Pratchett. Even The Onion sometimes makes me wince.

Jane, that’s probably a good way to look at these stories, not something you’d want to read a lot of but nice for a change.

You know, Conda, I’ve never read any Terry Pratchett. People have even compared my wiring to his and I’ve still not got round to reading him. I should fix that. I’ve never really thought of his as a satirist either.

And, Mr Lonely, thanks for dropping by. I’ve had a wee look at you blog.

Post a Comment