Ugly beauty – title of an article reviewing Larkin's Collected Poems

A poem is a difficult thing in itself, open to many interpretations; a collection of poems, by extension, must be a still more complex thing. What then of the life of the poet who wrote them? I think sometimes we forget how wholly inadequate words really are. I find myself slinking back to the same old subjects again and again because I'm never wholly satisfied with my previous efforts. Poems are private things that we insist on putting on public display, at least that is what they are for me, and I believe that is what they were for Philip Larkin too; he wrote for himself first and foremost. In a letter to the publisher D. J. Enright, Larkin said: "I think the impulse to preserve lies at the bottom of all art"[1]. I believe that's a fair statement. But just because a poem is a private thing we shouldn't assume it is necessarily revealing. That was made clear when Larkin's biography and letters were published after his death. Who was this man?

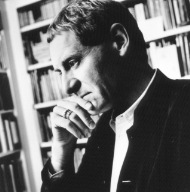

Any portrait of a man can only possibly be a partial affair; even a sculpture only reveals so much. The Larkin we see through his poetry is an honest snapshot of an unhappy and dissatisfied man. "Deprivation is for me what daffodils were to Wordsworth,"[2] he wrote but what was he deprived of one has to wonder. In one of the two quotes for which he will most likely always be remembered, the lines he ends 'An Arundel Tomb' with, Larkin wrote, "what will survive of us is love" and that is true if we're talking about love of Larkin; no less than three of his life's loves, Maeve Brennan, Monica Jones and Betty Mackereth (all of whom he dated at the same time), took turns watching over him as he lay on his death bed. But what of Larkin's loves?

The other quote for which he will be remembered is the opening line to 'This Be The Verse': "They fuck you up, your mum and dad." I actually think it'll top the line from 'An Arundel Tomb' not simply because it has an expletive in it, although that will do it no harm and will certainly get plooky-faced school kids to sit up and pay attention, but because the sentiment is one that the vast majority of us will be able to relate to long before we start to fret about what is going to remain of us. And there is no doubt that Sydney Larkin had a lasting effect on his son as did my father on me. I had certain beliefs hammered into me as a child and I cannot turn them off. My father recommended theology to me, Larkin's father was an advocate of National Socialism. Both of these held certain classes in contempt. My father's values have been passed onto me. Most are ones I no longer subscribe to but I find it hard to sit back and enjoy my own values because I constantly have to override his.

When his Selected Letters were published in 1992, "the magnificent Eeyore of British verse" as the Daily Telegraph once called him, was revealed to be, according to Andrew Motion, "a porn-loving misogynist whose views on race, women, the Labour Party, children, mainland Europe (and most of the rest of the world) were repugnant to any fair-minded liberal person."[4] How much of those values were imprinted on him by his father we can only guess.

I have a nagging voice inside me that tells me that homosexuality is "wrong, it's just wrong: 'You shall not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination.'"[5], and yet I regularly correspond with a number of gay writers without feeling the need to recommend a good woman to sort them out. One of my daughter's best friends is gay. She brought him over once and I clearly remember feeling uncomfortable around him (he was the first openly gay person I had ever met socially) and hating myself for that. I never told her. If she happens to read this then this will be the first she'll know about it. I get angry a lot of the time but indoctrination is hard to shake. There are lots of other things I could give as examples but you get the general idea. I just wish I was more comfortable in my own skin.

It is interesting to note that for all his right wing prejudices "homosexuality was rarely mentioned – or if it was mentioned it was usually treated tolerantly."[6] There is certainly substantial evidence that he was at the very least sexually confused when at public school and later Oxford although there is no evidence that he acted on these impulses.

Which brings me to the second line in that poem: "They may not mean to, but they do." Neither my father nor Sydney Larkin were bad men. They were both sincere in their beliefs. Larkin dedicated The North Ship to his dad and I dedicated Living with the Truth to mine. Despite all his failings I cannot say that, human frailties aside, he didn't live his life by his beliefs. And I expect Larkin could say the same. In fact he went into a panic when it was suggested after his father's death that he had been a member of 'The Link', a pro-Nazi organisation, but he could find no evidence in his paperwork to that effect. He couldn't dispute the fact though that his father, until 1939 at

One can react in one of two ways to one's upbringing: one can embrace it or one can reject it. Or I suppose there is a third, and I would expect more popular option, we can cherry pick.

The big question is, I suppose, can we separate Larkin the poet from Larkin the man? Personally I can. As soon as we pick up a poem by any poet we begin to take ownership of it. We want to make it our own. I personally don't give a toss about where Larkin was – or what his mindset was – when he penned 'Mr Bleaney', the poem is mine now. I actually know very little about the poem's history. It was a poem he completed soon after he arrived in Hull; he was living in Holby House, a student residence in Cottingham, a large village on the northern edge of the city. Bleaney was originally Gridley. His landlady was Mrs Dowling. And he had a miserable time there describing the place as "not suitable: small, bare floored and noisy: I feel as if I were lying in some penurious doss-house at night, with hobos snoring and quarrelling all around me."[8] None of that matters to me. I feel no burning desire to go on a pilgrimage there to try and capture the moment for myself.

Have you ever seen films set in the nineteen-fifties? If you have then it's a little easier to understand where many of his prejudices come from. There's nurture, nature and society. This was before TV, glossy magazines and people holidaying abroad. He was born into a black and white world where coloured people were really an unknown quantity, more feared than looked down on, which is perhaps where Britain differs from America, nevertheless, bigotry was still very widespread. Churchill apparently favoured the slogan "Keep England White"[9] something you'd associate now with radical right-wingers like the British National Party.

My father was ages with Larkin and I can still remember the kerfuffle when my sister simply suggested dating a … what is the politically correct term these days? … let's just call the gentleman 'a man of a coloured persuasion'. (The guy wasn't even a nice coffee-coloured mulatto – he was black as the night.) My parents weren't angry per se, rather, let's say, concerned in extremis. Nothing came of it and everyone breathed a sign of relief. Bear in mind it was 1965 before the first Race Relations Act came into force in the UK and one has to ask why such legislation was deemed necessary. Perhaps because surveys conducted in the mid 1960s revealed that four out of five British people felt that 'too many immigrants had been let into the country'.

I could go over the same ground when it comes to Larkin and my father's attitudes to women. The Equal Pay Act didn't come into force till 1963 and The Sex Discrimination Act followed in 1975. Again, simply look at the films of that time and you'll start to realise the world Larkin grew up in.

None of these arguments defend him from continuing to hold and express these views long after their sell-by dates but perhaps they explain a little why he was the man he was.

But back to the poetry. Is a sunset less beautiful if a murderer paints it? Or is a home truth less valid is a con man tells it to you? And is a poem about marriage any less moving when you realise that the guy who wrote it has been playing fast and loose with three women at the same time with not the slightest inclination of seeing any one of them right? For some of you I guess that would ruin it.

You see another side to Larkin after his father died in 1948 and his bi-weekly correspondence focuses on his mother whom he (affectionately from all accounts) referred to as, "Dearest old Creature," signing off simply as "Creature", "often drawing a sketch of himself as a whiskery seal-like animal wearing a muffler. [It seems like] this shift took place because Larkin knew Eva would find it consoling. It was a way of telling her their lives would always be cosy"[10] and in turn "Eva Larkin wrote to her son in a 'similarly doting, similarly trivial' tone to his own letters."[11] New collections of his letters are due out in 2010 – the 25th anniversary of his death – and it's hoped that these will present a softer side to the man.

I never wrote to my mother after my father died. I phoned once a week, every Thursday night, and I visited whenever the grass needed cutting. She didn't need more. She was a part of a very loving congregation and literally never went more than a couple of days on her own. But I did my duty and Larkin did his.

Larkin did not grow old very gracefully. In the evenings, after work, at home, "he would start drinking immediately (gin and tonic first, then wine), prepare the simplest supper ('something in a tin'), talk to Monica on the telephone, then listen to jazz and write letters … until he fell asleep in his chair."[12] In what we can trust to be one of his most autobiographical pieces, he began his poem 'Aubade' like this:

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what's really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

Short piece of 'Aubade' from the promo for

'Love Again' the life of Philip Larkin

Like most youngsters I experimented with drink but I learned very quickly that I don't have the stomach for it. Too many people close to me allowed it to get them in its sights and I was close enough to the fray to get caught in the crossfire. So I don't drink. The pills I'm on are bad enough without stirring alcohol into the mix. Besides I'm not alone. I'm quite sure it will be a different picture for me if I ever have to endure too many years by myself before my own end, not that I dwell on it. I rarely ever think about it, unlike Larkin. "In his lifetime it was generally thought that the focus of his interest was death, and that what bound his poems together were themes of mortality."[13]

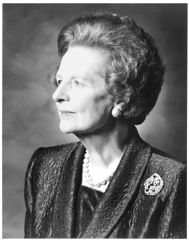

"[W]hen Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government was elected to office he praised her to anyone who would listen. Ever since Thatcher had become leader of the party in 1975 he had admired her, for her looks as much has her polices. 'She has a pretty face, hasn't she,' he had written excitedly to Eva, 'I expect she's pretty tough.'"[14] Surprisingly she was fond of his poetry and offered him the laureateship on the death of Betjeman. He declined. She was "very understanding". And a few years later, just before his death in fact, she arranged for him to be made a Companion of Honour although he proved too ill to attend the investiture.

I remember when the Tories came to power. I had been married only a few months and my wife and I were living in a privately rented flat in East Kilbride. As it happened, my best friend's girlfriend was staying with us to make getting to university easier. The morning of the election results she actually woke us up to tell us who was in. She had the kind of expression on her face that a woman has when she's just been proposed to. She was such a fervent Tory that she'd even arranged to vote by mail since she couldn't get home to cast her vote. I hadn't bothered to vote at all.

Why, I wonder, has Larkin been maligned for being a Thatcherite when the majority of the country clearly wanted the Tories in power and her in charge? It beats me.

When I read Larkin's biography – my daughter bought me a nice hard backed copy for my birthday – I cannot pretend I was surprised at a lot of what I read. Disappointed? No, not that either. Biographical or not, what kind of man did I expect to have written the kind of poems he produced? I felt the same when I read my biographies on Beckett. It was no surprise to find out he was a miserable git. I'm a miserable git.

"[F]ollowing the publication of the Letters and the Life, a few librarians removed Larkin's poems from their collections, and some critics conflated their sense of his personality with their account of the poetry to condemn its entire foundation."[15] A typical knee-jerk reaction. But you cannot unread what you have read. You may be reading this article and this is the first you've read about the 'real' Mr Larkin. If so I make no apology for shattering any illusions you may have had. That's what illusions are there for, to be shattered. And, yet, for all that, some people still insist in air-brushing his life: Yes, okay, so we know the truth, but do we have to talk about it?

No. No, I don't suppose we do.

I'll leave the final words to John Banville. There's a link to his homage to Larkin below:

All this, of course, is incidental to what matters, which is the poetry. We do not judge Shakespeare's plays because he willed to Anne Hathaway his second-best bed, or Gesualdo's music because he murdered his wife. In time, when the dunces have been sent back to their corners, what will remain is the work

Further Reading

The Art of Poetry No. 30, Philip Larkin, The Paris Review, Issue 84, Summer 1982

'Homage to Philip Larkin' – John Banville, The New York Review of Books

'Revealingly yours, Philip Larkin', The Sunday Times, May 11, 2008

'Amis on Larkin's life, loves and letters' – an long audio panel discussion at Centre for New Writing, Manchester University

'Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life' – Vereen Bell, The Southern Review, March 22 1994

'Without Metaphysics: The Poetry of Philip Larkin' – Brother Anthony (An Sonjae). A 1992 paper written before the publication of the letters and the first biography.

'The Poet of Political Incorrectness: Larkin's Satirical Stance on the Sexual-Cultural Revolution of the 1960s' – Fritz-Wilhelm Neumann (Erfurt)

'Philip Larkin - A Stateside View' – Robert B. Shaw, Poetry Nation, No. 6, 1976

'Larkin's first interview' – John Shakespeare, Times Literary Supplement, April 1, 2009

References

[1] Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life – Andrew Motion, p 273

[2] Required Writing: Miscellaneous Pieces, 1955-82, p 47

[3] 'Homage to Philip Larkin' – John Banville, The New York Review of Books, Volume 53, Number 3

[4] 'The Quarrel within Ourselves', The Guardian, Friday 14 March 2008

[5] Leviticus 18:22, American King James Version

[6] Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life – Andrew Motion, p 65

[7] John Kenyon, Larkin at Hull quoted in Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life, p 12

[8] A letter to Judy Egerton, 24 March 1955 quoted in Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life, p 247

[9] On Commonwealth immigration, recorded in Harold Macmillan's diary entry for 20th Jan 1955 (Peter Catterall (ed.), The Macmillan Diaries: The Cabinet Years, 1950-57, p 382)

[10] Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life – Andrew Motion, p 177

[11] 'From their own Correspondent', The Guardian, Tuesday 11 March 2008

[12] Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life – Andrew Motion, p 449

[13] Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life – Andrew Motion, p 291

[14] Philip Larkin, A Writer's Life – Andrew Motion, p 479

[15] 'A Fanfare for the Common Man' – The Guardian, Saturday 5 July 2003

21 comments:

D'you suppose it's necessary to be a "miserable git" to be any shakes as a writer? I've personally always worried that I'm far too generally content and lacking in notable traumas to have any really good wells of rage, anger, and pain from which to draw Art. (And I've noticed that my protagonists tend towards the bland and agreeable, surrounded by more colorful and vibrant characters. Curse this reverse-reverse psychoanalysis via writing samples!)

I'm with the Russian Formalists on poetry reading. I adore Larkins poetry, though dislike what I know of the man behind them (I feel a little like this with Orwell, too). My favourite Larkin line is: 'my mind will fold in on itself; like fields; like snow.'

That rang a few bells for me on the personal level, Jim. The business of returning to old subjects because we are nor satisfied with what we said before and poems being private things on public view.

As regards separating the man from the work, I think you almost always have to do that. I know the one can throw light on the other, but the light does not always reveal. It can fog. In Larkin's case I am not sure. It is certainly true that some right bastards have written beautiful verse. A very thought-provoking post about a poet I have never been able to make up my mind about!

I have Larkins 'High Windows' I really enjoy its melancholic morbidity and sterile seriousness and the moments of beauty he captures so plainly and yet eloquent.

I know all about his 'real' life, he was a miserable git, a thrifty misanthrope who hated children and most other things in some measure. A lone drunk, almost an ascetic; there is something cruel in his misery and out look but this is only natural when you consider how hard the path of life and death can be.

Larkin has a kind of beauty designation with his attitude towarss life; he can't stand it and yet he does. Like us all. As for his Tory background and mean-spiritedness, they sing through all his poetry and I they don't make me dislike him. We are all horribly biased as human beings. We all have disgusting prejudices of our own liking.

I didn't realise you felt homosexuality to be 'wrong' (i.e. morally wrong.) That will be your 'Christian' up bringing. I mean, you're not a religious man, but we all still carry to baggage of that kind of 'moralising'. Also, being heterosexual, it's natural to feel uncomfortable around it.

Sexuality is as flawed as any gene pool perhaps. Sexual liberation did not hasten in universal love, but perhaps it made some forms of love less controversial.

I have a hard time with sexuality, I've had relationships with men and women, and quite frankly, I am quite happy with it. It doesn't baffle me. It doesn't make me hate or believe that heterosexuals are incomplete or missing something.

Anyway, I might go re-read some Larkin, it has been a while. Speak soon.

Scattercat, I don't think it's a prerequisite but I've always found it a great help. I really don't work well with positive emotions and I don't think that many poets do. What you need is a good breakup or your cat to die. I'd say just watch the news to bring you down but artificial highs and lows beget artificial poems in my experience. You've gotta feel the pain.

Rachel, what is it with you and snow? I think what's so great about that line is what it follows. 'The Winter Palace' really isn't that poetic up till that point, just an old guy whinging away about getting on, and then we have this wonderful image right at the end. Brilliant.

What gets me, Dave, is that I really thought by my age that I would have worked out most of the things that were bugging me as a kid. It's really a lot to do with indoctrination, you are told to see the world a certain way and when you get older and rip the rose-tined specs off you realise that you've got rose-tinted eyes, so what do you do? Pluck 'em out? I am always going to be preoccupied with issues of meaning and truth. Other things may well distract me but you have no idea how many times I get an opening line for a poem with the word 'truth' in it.

And, McGuire, yes, I have real issues with indoctrination. Any kind, not simply religious. Bigotry was rampant when I grew up. Not just at home but in the schoolyard as well. I think that's why Nineteen Eighty-Four had such an effect on me when I first read it. So let's be clear. I don't think that homosexuality is wrong (intellectually I'm quite comfortable with it – I just don't want to do it but then I don't want to go white water rafting either) but I have to resist a feeling that it is wrong. That goes beyond what I was taught growing up. One can reject certain teachings but not feeling guilty about it afterwards is another thing entirely.

If I can shift this away from the emotive issue of sexual preference and talk about smoking and drinking both of which I have done if only as an outward demonstration of my inner rebelliousness. I could do both but I knew what I was going was wrong so my enjoyment was tainted. I tried swearing too but it's really not me. I sometimes get my characters to swear on my behalf.

You used the word 'natural' but really it's 'nurture' we're talking about here. My natural development was interfered with. Decisions were made on my behalf but at least my parents didn't call me Lenin as one young lad's mum and dad did who were fervent Communists; there's always someone worse off than you.

come and collect an award on my blog!

Snow is beauty and cruelty at its most sublime. I love the whole of that poem, as a deconstructionist, 'I have spent my lifetime trying to forget' (paraphrasing from memory here - before you go get your book and tell me I misquoted!)is a dream sentence to read. I adore Larkin's poems. It's like you and I, Jim, the chances of us 'chatting', were it not for poetry or prose, would be slim indeed.

Tony, thanks for considering me but I've decided to opt out on awards like this, the kind where you're expected to pass the thing onto a load of sites you deem worthy. Like I said though, it's nice to be thought about.

And, Rachel, perhaps growing up in Scotland I find it hard to romanticise snow. I can still remember my childhood trudging through the stuff in my wellies my feet like blocks of ice. Brrrrr. I had a look and I can only find one snow poem in my collection which you may or may not appreciate but here it is:

The Truth Behind All Poems

This was

a blank sheet

of paper before

I did this to it.

Footprints

in the snow

mean next to nothing.

Learn to read between

the lines.

Kids get it.

They know exactly

what to do when they

gaze through

that window:

there’s no place for

perfection in an

imperfect world.

Saturday, 16 July 2005

Thanks, Jim, I like your poem more than your morals! I'll never tire of snow. Going to call you 'Truth' Murdoch now! But of course there is no one definition of snow, just as each flake is unique, that's the beauty of it. And it is as subjective as truth.

I've got Larkin's "Required Writing" book of reviews and essays. It's terrific reading although I think his prejudice against all kinds of jazz that came after bebop was problematic to the point of keeping Larkin from appreciating jazz in general. He was fixated on one kind of jazz, and hated all others.

I think I have a Selected Poems here, too, but I need to pick up the Collected when I find it. It would be interesting to go through it all, at this point, which I haven't done before. I've always liked some of his work, but have had problems liking all of it. And I find it hard to like him, as a person. If I can be permitted an unfair comparison, another famous librarian-writer, Borges, was someone I always felt I could sit down and have a fascinating and fun conversation with. I always rather felt that wasn't ever going to be possible with Larkin, at least not for me.

The theory of "you have to big messed up or a bastard to be a great artist" is one I do not subscribe to. I think it's BS, frankly. It maintains the Romantic myth of the hero-artist by making him or her into an anti-hero-artist, but it doesn't really mean anything. Wagner was a horrible person; Debussy by most accounts was a wonderful person; yet they both wrote great, masterful music. So there's no correlation between art that someone makes, and their character. There never has been, and it's foolish to think there is. (IMHO.)

I read an interview once with someone who worked for Larkin and his description of him as a boss was quite Draconian, very unapproachable. He wasn't a very sociable person part of which resulted from a blinkered view of life. So, there were those who he saw eye to eye with like Amis and Thatcher and then there were the rest of us.

In his Paris Review interview he's asked about Borges and I'm not sure if he's being flippant or deadly serious in his response (I suspect the latter):

INTERVIEWER

Is Jorge Luis Borges the only other contemporary poet of note who is also a librarian, by the way? Are you aware of any others?

LARKIN

Who is Jorge Luis Borges? The writer-librarian I like is Archibald MacLeish.

As for the "messed up bastard" theory I'm probably not well suited to comment being a long-standing messed up bastard myself. Personally I can't imagine anyone not being a messed up bastard even Debussy. I certainly don't think being a messed up bastard is a hindrance. As far as the writing profession goes it's probably a boon.

Do I detect from what you say that it worries you a tad that you have this compulsion (probably not the right word: idée fixe?)to write about truth. It is not necessarily a minus, as I'm sure you know many greats painted the same picture or wrote the same poem throughout a greater part of their oeuvre.

'Worried' is not really the right word, Dave. I'm just tired of it and yet, like an addict I'm drawn back even though it stopped being fun a long time ago. I'd like to quit – and I plan to – but I couldn't set a date for that. It's like the old Freudian 'joke' that everything boils down to sex, with me everything boils down to truth, even sex is a search for truth, the desire for it (and what that revealed), getting it (and what that revealed) and then going back for more (and what am I, an onion?) and thirty-odd years on, it's place in my life continues to reveal more. Truth is the heartburn you get after a good meal or the trapped wind.

I don't so much feel that I'm painting the same painting over and over again so much as aspects, bits of the same painting, an ear here, a nose there, only I have no real idea what the 'big picture' looks like. Probably the most important thing I learned about in recent years was the notion of fuzzy logic. I had always been led to believe that truth was something sharp and in focus whereas for all of us it's really something out of focus; if we squint then it gets a bit clearer but it's always just a bit blurry around the edges.

Rich in detail and pithy comment as ever, Jim, but thanks in particular for PL reading what might actually be the 20th century's greatest meditation on love and time.

Dick, there are not very many people who could just justice to a Larkin poem apart from the man himself. Clement Freud, perhaps, or Les Dawson.

So glad I peered through the 'High Windows' of the internet to find this insightful blog. Even at 'first sight', I feel this is the prefect place to sow my "wild oats"! Please feel free to check out my blog, johnbakersblog.blogspot.com - it's not at all 'aubade'!!!

Thanks for leaving a comment, John. Confused me a bit at first because I have a novelist friend called John Baker. References to Larkin crop up not infrequently on my blog mainly nod to his poem ‘Mr Bleaney’ which had such an effect on me all those years ago. I’m glad you found the site in general worthwhile. I’m not the most knowledgeable poet out there but as I learn new stuff I like to pass it on and there is still a lot about Larkin I have yet to discover.

Having just finished Andrew motion's biography of Larkin, I'm wondering if the nurse who was with him when he died misheard his last words.

Is it possible that he actually said: "I am BOWING to the inevitable."

which to me makes more sense.

Doesn't really matter I suppose. bowing is going, in a way.

Oh, I think there's a big difference, Miranda. There's a resignation to the word 'bowing' that suits Larkin. As you say we'll never know but I think you might be on to something. Thanks for the comment.

"But the thing is, being a writer – or more often than not, not being the writer he wanted to be – was a major preoccupation with him."

Rather more, not being the writer he didn't want to be.

“When I throw back my head and howl

People (women mostly) say

But you've always done what you want,

You always get your way

- A perfectly vile and foul

Inversion of all that's been.

What the old ratbags mean

Is I've never done what I don't.

That's true of his writing as well as his life, I think.

His poem for the Humber Bridge showed Larkin could write good vers d'occasion if he chose and his early parodies show he could churn out routine fiction. What happened in verse and fiction, I think, was that he couldn't write what he wanted to write and refused to do anything else.

Yes, Roger, I suspect you’re quite right there. Of course now he’d dead and those whose opinions of him we could trust are dying off too—assuming they’d tell us the truth anyway (old friends can be very protective)—I guess we’ll never know for sure. Did you happen to see the article in The Guardian yesterday? It seems a letter from Larkin has been discovered in a college safe in which he refuses a position of professor of poetry at Oxford. In it he writes, “I have never considered literature in the abstract since that blessed day in 1943 when I laid down my pen in the Sheldonian Theatre and sauntered out into the sunshine, a free man; anything I have written since then has either been hack journalism or cries wrung from me by what I believe Gide calls the frightful contact with hideous reality.”

Post a Comment