Identity is such a crucial affair that one shouldn't rush into it. – David Quammen

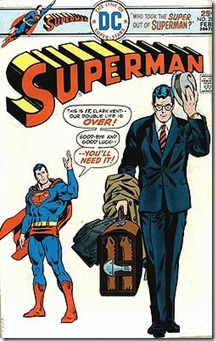

Here’s another one of those words that we use all the blinkin’ time and think we understand: identity. The first thing I think of when I hear the word ‘identity’ is Superman, as you do. He has a secret identity (Clark Kent). As does Batman (Bruce Wayne), the Flash (Barry Allen amongst others), Daredevil (Matt Murdock), Spider-Man (Peter Parker), Captain America (Steve Rogers) but not Thor; he used to be Donald Blake but now he’s pretty much Thor all the time and let’s face it everyone knows who the Fantastic Four are and the closest the Thing ever gets to a secret identity is slinging on a mac and a trilby. I don’t have a secret identity. I don’t even have a cape.

In philosophy, identity (also called sameness) is whatever makes an entity definable and recognisable, in terms of possessing a set of qualities or characteristics that distinguish it from other entities. Or, in layman's terms, identity is whatever makes something the same or different. – Wikipedia

Identity is whatever makes something the same or different. Now that is a sentence to sit and mull over along with cup of coffee and a plate of biscuits.

We all value our individuality but at the same time we want to be one of the gang. It’s like wanting your cake and eating it, isn’t it? Most of us start off our writing lives by identifying with some writer and trying to imitate them making them our role models. We want to be a writer like them. At first we feel our words need to be like theirs but then we realise that if we simply sit at a desk and write on a pretty regular basis then that works too. I don’t think there’s any one of us who isn’t just a little curious about how other writers work, what hours they keep, what their office looks like, how many words a day they think is ‘normal’.

I didn’t do that so much. I never idolised any particular writer. I adored Larkin’s poem ‘Mr. Bleaney’ but I wasn’t that interested in the rest of his stuff. Or him. So my first role model was a poem, not a person. Later I added a poem by William Carlos Williams but even though I bought a book of his poems it was just the one poem, ‘The Locust Tree in Flower’ (the compact version) that caught my attention. Apart from a couple of Williams-esque poems I never tried to imitate either writer at the time. It was the spirit of the poems that I adopted. I never looked for biographies on them or anything like that. I really wasn’t very interested in the writers. I only discovered what Williams looked like a few years ago. I was taken by what they’d written and I’ve always found that to be the case.

But back to Superman/Clark Kent, real name Kal El. Secret or not ‘Clark Kent’ is an identity but then so is ‘Superman’. Who then is Kal El? How do you identify Superman? The outfit with his underpants on the outside, the billowing cape, the ‘S’ logo. If he didn’t dress like that you’d have to wait for him to leap a tall building in a single bound before you’d know, either that or tell you what colour underwear you’re wearing, something like that.

Self-esteem is a term used in psychology to reflect a person's overall evaluation or appraisal of his or her own worth. Babies don’t have self-esteem. They don’t look pleased with themselves when they burp or fart at least not until they notice that it gets a favourable response. We have a cockatiel that does that. Every night now when he gets put into his cage he clambers up on the front and does ‘wings’ which in birdy-gestures is the equivalent of giving us the finger: I do not want to go to go to bed now! And how do we respond? We ooh and ahh and generally make approving sounds, the kind of sounds we usually make when he rings the chimes in the window or does something clever. You can almost see the confused look on his face but the simple fact is that he’s started doing it more and more because he obviously likes the approval. He feels good about what he’s doing but is that really self-esteem since the approval he gets comes from outside him?

Self-esteem, self-worth, is not a simple thing to calculate. And at different times in your life certain things are more heavily valued – perfect skin as a teenager, a facility with words when chatting up girls – it all depends on what’s important to you at the time. But how do you know if your assessment of your true worth is accurate? You need an assessor. That makes one think immediately of an individual, a person who we go to to look for some kind of validation but I think we can look at it more broadly. We need a way to assess ourselves. That’s where setting goals comes into play. I toyed with the idea of saying ‘ambition’ but I’ve always thought about ambition to be as much of a negative as a positive quality which it may or may not be depending on the individual and what they’re willing to do to meet their ambitions. Also ambitions tend to focus end-of-the-road achievements, like becoming captain of the football team or something like that. Goals are what you score on the way there.

For writers goals can and should start off quite modestly. I think the first big one I had to reach was to develop perspective. When I first started writing I pretty much thought every time I put pen to paper I was capable of producing a work of staggering genius and it was only a matter of time (and not a very long time) before I wrote one and then, after getting the hang of it, the next work of staggering genius would be a lot easier until every time my pen touched a piece of paper raw, undiluted genius would flow onto the page. I charted my changing views of myself in this poem:

Borrowed Knowledge

As a child

I knew I knew everything.

No one believed me

and over time I

forgot most of it.

When a man

I thought I knew many things.

I knew of many things

and I believed

the things I knew were mine.

Now, of course,

I've grown old and it is clear

to me I knew nothing.

It is the one

thing that I know for sure.

Two plus two

is not mine, nor the capital

of Venezuela,

nor the reasons

I'm all alone tonight.

2 October 2007

As it happens I wasn’t physically alone when I wrote the poem but I was alone in the respect that I was still writing in isolation. With the exception of my wife, who by that time had pretty much stopped writing anyway, I had only actually met two writers in the flesh, both friends of my wife as it happens. In August I had started my blog but if I got half-a-dozen hits a day I was jumping for joy. I still felt very much alone. I was a member of the set of imaginary writers. I knew there were other writers out there but they weren’t real to me.

My big problem when I first started out was I had no accurate means of mensuration at my disposal. I knew no other writers. I didn’t know how to be a writer, good, bad or indifferent. I’d look in the mirror and try as I might I couldn’t see a writer looking back at me. I couldn’t tell you the day I looked into the mirror and saw a writer looking back but it was quite a while after I looked into the mirror and saw a man looking back.

A few days ago, for only the third time in my life, I went to a gathering of writers, not a virtual gathering but a literal one in an actual pub with real people who complained because I apparently have a firm handshake. The first was a poetry reading I’d been invited to at which I spoke to no one and no one spoke to me; the second was some writers thing in Prestwick of all places and all I can remember about that was hearing Tony Warren talk about Coronation Street – both of those were thirty-plus years ago. This time it was a monthly gathering of writers in Glasgow called ‘Weegie (as in Glaswegian) Wednesday’ at which I got to chat to a nice girl called Stephanie originally from Utah and a couple of others who ended up sat at the table from which I didn’t move all evening except to order a second Diet Coke and to leave. Everyone was nice, very nice, but it got very noisy and crowded and noisy crowds are not really my cup of tea. I don’t like conversations that have to be shouted and I usually end up sitting around regretting never having learned to lip-read. But what really got me was how uncomfortable I felt about myself being there as if I was still pretending to be a writer, as if I hadn’t earned the right to be there.

If I were to pick a verb to go with the word ‘self-esteem’ I think it would be ‘bolster’, as in to support or reinforce; strengthen. One of the main reasons to attend a gathering like that is, I guess, to encourage one another: Look! You’re not alone, there are loads of us flogging the same dead horse and trying to get blood out of stones – you are not alone. And if one of the group has a bit of success then it proves that success is possible because you know a flesh and blood person who actually managed it. There was a girl at my table who had just sold a book and everyone looked so pleased for her and it seemed genuine. That was nice. It was nice that people took encouragement from someone else’s good fortune. And it was to the girl’s credit that she downplayed her success.

Writers don’t usually have thick skins – it’s a side effect of being sensitive souls – and right under our skins lies our self-esteem. It’s the first thing that gets it when we get praised or criticised. Self worth is like an IQ. A high IQ signifies potential, nothing more. A six-year-old can have an IQ of 200 but what will he have done with it in his six years? Self worth is the difference between talent and skill: a skilled craftsman is not necessarily a talented one. And by ‘talent’ I mean a special natural ability or aptitude. Skills come with practice and even the best, the naturals, the Lang Langs and Yehudi Menuhins of this world need to practice to develop their skill set.

The question is: are you basing your self-worth on what you have produced or on what you believe you can produce? If I believed that I had written the best poem, the best short story, play and novel that I was capable of then what am I doing still writing? People judge by appearances. They judge people – other people but also themselves – by what goes on outside of the body, the extra few pounds they might be carrying, the fact that their boss is younger than them, the fact they’re still living with their parents as if all or any of that is an accurate way of measuring worth. And people will judge us by what we produce but only we know what we’re capable of.

A writer is, it is said, his or her own worst critic which is why many re-write their material over and over until they get it right. That’s not a bad thing and probably one of the biggest mistakes newbie writers make is not appreciating the importance of editing their material, but that’s a skill thing – it has nothing to do with talent. There is a danger though that you find you’re never satisfied and simply can’t let go of the material. Again this is a skill thing, knowing when you’ve done the best you can at the time even though you know that in time you could do much better. You will do much better. We all do. But not everything we write has to be a work of staggering genius because most people really don’t want to read works of staggering genius.

Just as an overweight person can use that as the sole measure of their self-esteem I think that writers can do much the same. I’ve hardly written a word for the past three weeks – it happens, I’ve been doing other stuff – and now I’m sitting here at 1:30 in the morning because I’m on a roll and feel I need to write while the ideas are flowing. I’m happy writing. I’m doing what I should be doing. I make sense now. Not being able to fix the new toilet seat a couple of weeks back made me feel bad but if I’d sat down and started writing all that would have been forgotten very quickly because toilet seats aren’t important; writing is.

What is a writer? In its most simplistic terms it is someone who writes. I write ergo I am a writer. But how I define the word ‘writer’ is far more complex than simply equating it to the act of writing. Stephen King is a writer so is Doris Lessing, Joyce Carol Oates, Douglas Adams, Neil Gaiman, etc., etc. Add to that several million other writers and you get a composite picture of what a ‘Writer’ is. I am a member of the set of writers. And my place in the pecking order, how I feel in the company of other writers, clearly affects my self-esteem. I can certainly identify with them – Stephen King sits at a desk like me and writes onto a laptop like me (in that respect we’re the same) – but I’m also acutely aware of the differences between me and him. Remember how Wikipedia defined ‘identity’: “identity is whatever makes something the same or different.”

I learned a new expression today: collective self-esteem. Seems a bit contradictory at first but here’s how it’s defined:

That part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership in a social group(s) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership – Henri Tajfel, Human Groups and Social Categories, p.255

I had never heard this term before but it’s an interesting one I think. If I were to drawn a Venn diagram of writers it would be a dirty great big circle with all the writers in the world inside it. It’s not that simple though. We have all kinds of writers in that circle, amateurs, professionals, hobbyists, all vying for a good place. Where do I fit in the pecking order? In a room full of writers the calibre of most of which were quite unknown to me I chose to feel small even though I had probably written more than each of the three ladies I was at the table with if only because I was about twenty years older than each of them and so had a head start.

In his book Language and Identity: National, Ethnic, Religious (p.76), John Earl Joseph identifies five positions that are embedded in Tajfel’s proposition:

- that social identity pertains to an individual rather than to a social group;

- that it is a matter of self-concept, rather than of social categories into which one simply falls;

- that the fact of membership is the essential thing, rather than anything having to do with the nature of the group itself;

- that an individual's own knowledge of the membership, and the particular value they attach to it - completely 'subjective' factors - are what count;

- that emotional significance is not some trivial side effect of the identity belonging but an integral part of it [italics his]

Can you imagine how he would have felt? Superman is the quintessential superhero and even as a boy he must have realised this. It was bad enough that he had to hide his true identity from most of Earth’s inhabitants and so was well used to not belonging but to be rejected by his peers or if not rejected outright and only then afforded ‘honorary’ membership, that must have stung. But like I said at the start, I’m no superhero. But I’m also not ordinary. I’ve never felt ordinary. And I’ve longed to belong, not in an abstract sense because I belong to lots of different sets, but in a let’s-go-for-coffee sense.

Tajfel was the first to conceive of a collective self-esteem but it was nine years later that Riia Luhtanen and Jennifer Crocker in an article in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin proposed a system of assessing it. It can be tweaked according to the ingroup that the person being assessed is affiliated with but this is how is would work for a writer:

Please read each item carefully, and respond by using the following Likert response scale:

- = strongly disagree

- = disagree

- = disagree somewhat

- = neutral

- = agree somewhat

- = agree

- = strongly agree

- I am a worthy Writer.

- I often regret that I am a Writer.

- Overall, being a Writer is considered good by others.

- Overall, being a Writer has very little to do with how I feel about myself. [1]

- I feel I don’t have much to offer to other Writers.

- In general, I am glad to be a Writer.

- Most people consider Writers, on the average, to be more ineffective than people from other creative disciplines.

- Being a Writer is an important reflection of who I am. [7]

- I co-operate with other Writers.

- Overall, I often feel that being a Writer is not worthwhile.

- In general, others respect Writers.

- Being a Writer is unimportant to my sense of what kind of a person I am. [1]

- I often feel I’m useless as a Writer.

- I feel good about being a Writer.

- In general, others think that Writers are unworthy.

- In general, being a Writer is an important part of my self-image. [7]

-

Items 2, 4, 5, 7, 10, 12, 13 and 15 are all reverse coded.

The Collective Self-Esteem Scale captures four different aspect of collective self-esteem:

- Membership esteem: how one judges oneself as a member of the group (items – 1, 5, 9, 13)

- Private esteem: how one judges the group itself (items – 2, 6, 10, 14)

- Public esteem: how one judges how others evaluate this group (items – 3, 7, 11, 15)

- Identify esteem: how one judges the importance of one’s membership in this social group to one’s self-concept (items – 4, 8, 12, 16)

Do I need to be a member of the Set of Writers to be a writer? No. I don’t need to join any organisation, pay any annual fee, wear a badge or register myself anywhere. That doesn’t matter. I know there are other writers out there and no matter how hard I try to say that my relationship to these literally millions of strangers doesn’t matter the fact is it does. Avoiding all contact with other writers might help but it’s not the answer.

Of course there are subsets to which I belong. I’m not simply a writer, I’m a member of the Set of Poets, of Scottish Writers, of Male Novelists, Self-Published Writers, Writers Who Blog, Children’s Writers With Beards and so on and so forth. My self-esteem as a Poet is better than my self-esteem as a Playwright for example: I’ve been paid for my poetry but I’ve never even offered one of my plays to a local theatre group to see if they’d fancy a crack at it.

I’m not suggesting that any of you should take the test but feel free to. I do think the questions are interesting though and worth thinking about. You’ll note that I did actually answer four of the questions. I’ve since had a think about those answers and I’m not sure the answers are accurate because what I was answering was really how I felt about being a writer not how I felt about being part of a group made up of writers. That’s not so important to me. That said I can’t pretend I don’t have a need to be accepted for who I am, to take off the glasses and don the cape or maybe the other way around.

And to end on a light note I’ve just discovered there is a Collective Self-Esteem Network on Facebook (it’s affiliated to the Mutual Admiration Society) where fellow members “give Facebook hugs in a totally Care Bear loves Pedicab way!” I’m not joining. I have enough problems with the groups I’m already a member of.

Further Reading

For a short explanation of collective self-esteem’s four aspects see Julie A. Garcia and Diana T. Sanchez’s article here.

A clear explanation of Likert scaling can be found here.

Normandy

Normandy

Karin Alvtegen-Lundberg

Karin Alvtegen-Lundberg