Let’s just stick with the 8000 adult hardbacks for a moment and imagine them all lined up for us on a ve-e-ry long shelf and let’s say that we looked at each cover for a whole 1 second. It would take you two and a quarter hours just to look at them. Some studies show that you actually have a whopping great twelve seconds in a bookstore to turn a browser into a buyer. And, of course, what will appeal to one potential reader is going to turn another one right off. Here’s an example. While I was working on this blog I talked a bit about it to my friend Koe (the half-life of linoleum) and he told me about a couple of books he’d been attracted to purely on the basis on the covers. One was The Disappointment Artist by Jonathan Lethem. This is what he had to say:

I think what appealed to me about the cover when I first saw it was just the literal humour. The poor kid whose ice cream is melting in his hand. I am pretty sure that it seemed to me then that there was a lot more ice cream melted on his hand than had come off the ice cream. It looked worked on by the art director – that an ice cream melting rarely looks like a melted ice cream. I thought the image just very clever.

When I was a kid I used to eat an ice cream like this when the Good Humour truck stopped in the neighbourhood but back then – Good Humour gave out napkins with a little die-cut in the middle that you put the stick through to save your hand from the melting. This child appears to be a disappointment . . . it never would have taken me that long to eat an ice cream - it would never melt in my hand. How could this even happen?

Today, I am looking at this cover a bit more earthily perhaps . . . it almost looks pornographic. I asked my wife what she thought of the cover just now and she said something along the lines of, 'it grosses me out, I'm a mom, I want to clean this mess up.'

Personally I loathed the cover. I would never in a million billion trillion years have picked it up. Even the thought of using the image in my blog makes me uncomfortable because I hate runny messes like that. Even as a kid if a single dribble of ice cream started running down the side of my cone I'd lick it off. In fact my usual approach to eating a cone was to bite off the end and suck the ice cream inside where it would be contained. There is no way I would have given that cover twelve seconds of my attention. Of course others say that twelve seconds is a gross overestimation and that a mere three seconds is a more realistic estimate. Personally I’d say three seconds on the shelf and twelve in my hand.

What we’re talking about here is what some people call The Glance Test.

Let’s give it a test. Here are a selection of covers to novels by Iain Banks. See which one jumps out at you. You have about three seconds to view each one:

For me it was Whit followed by The Crow Road and in both cases the titles improved the book’s chances. What you might not have noticed is that there were two different covers for most books. When his books started coming out they were published with monochrome covers, white-on-black for one followed by black-on-white for the next and much as people used to argue about whether the merits of the odd-numbered Star Trek films as opposed to the even-numbered, people would also argue about whether the books with the ‘black’ covers were better than the books with the ‘white’ ones. The publisher has now reprinted all the books and I’m not impressed with his choices. But you might like them.

The thing about Banks now is that he is established and so you could put pretty much anything you like on a cover and people will pick it up. Certainly in the UK. Not sure what his international reputation is like but if you’ve never heard of him then he is worth checking out. He is the author of my favourite opening to any book:

It was the day my grandmother exploded. I sat in the crematorium, listening to my Uncle Hamish quietly snoring in harmony to Bach's Mass in B Minor, and I reflected that it always seemed to be death that drew me back to Gallanach.

That’s from The Crow Road. But this is an article about covers not opening lines.

The key is simplicity. But passing the Glance Test requires a few issues to be addressed:

Create a Compelling Title

What makes a great title? In a word: brevity but brevity that piques interest.

How Much Text is Good Text?

Less is always more when it comes to text first impressions. Reduce your text to the absolute minimum necessary and stick to the point. Many book covers end up cluttered with endorsements, quotes, stickers all of which are using up your precious three seconds.

Keep it Consistent

The branding, image and tone of your book cover must reflect the marketing you do in other areas of your business – e.g. I use the same font on my blog as I do on my books. Consistency in the "look and feel" of your business colours, text and service offering will help people remember you.

It contains the most basic of information. But that’s all it needs to do. All the rest can be on the back cover or the flyleaf.

Up until now I’ve only talked about books that pretty much will sell themselves. What about a book by a complete unknown which most authors are to most people on the planet? Here are two covers to the novel Eat the Document by Dana Spiotta.

Bad enough that we see a monochromatic image of a woman clad in a sweater and jeans that tells us absolutely nothing about the book. (Is this an academic response to Our Bodies, Ourselves or a novel?) But that horrid yellow text, intended to capture the wretched typographical triumphs of the 1970s, causes this eyesore to be a classic case of a book being unfairly discriminated against by its cover. No wonder this fantastic novel didn’t sell so well earlier this year. Thankfully, the paperback version has a much better cover. – Edward Champion, ‘Worst Book Cover of 2006’, Edward Champion’s Reluctant Habits, 8th December 2006

Personally neither cover does anything for me. I prefer the first one but then I got to thinking about people seeing me read it on the bus and that kinda put me off it. But Champion is right: what do the covers tell us about the book? Nothing. Which is bad but misleading is worse. Here are two covers to The Yellow Wallpaper.

‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ is a six-thousand-word short story by American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, first published in January 1892 in The New England Magazine. It is regarded as an important early work of American feminist literature, illustrating attitudes in the nineteenth century toward women's physical and mental health. The story also has been classified as Gothic fiction and horror fiction.

As best I can remember there are no naked ladies just a woman quietly going out of her mind while supposed to be resting in bed. Why did I pick it up? Because of the naked lady? Actually because it was a thin book – very thin actually – and I’m drawn to thin books. As best I can remember all I had to go on was the spine at the time. It was what was on the back of the book that helped me make my mind up. The cover with the wallpaper on is okay but nothing to write home about.

In the story, the unnamed narrator is imprisoned in her bed for a postpartum "rest cure" on her doctor-husband's orders. She hates her rented room, especially the partially stripped-off wallpaper, which is in "one of those sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin" and has a "repellent" colour, "a smouldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight." I need to ask the question: Should the cover show any wallpaper at all because surely it’s best to leave that to the imagination of the readers? (Just in passing I found a radio dramatisation of the book here which you might find interesting. There’s also a BBC dramatisation in 8 parts which some nice person has uploaded to YouTube.)

But back to unknown authors. Here’s another wee slideshow for you:

The key word here is, of course, UGLY. Sometimes it’s meant literally, other times it’s figurative. To my mind the most memorable cover is the movie poster I slipped in but then, like I said, I like minimalistic presentations.

Have you ever bought a book just because it had a cool cover? I’ve certainly bought comics just for the cover art and LPs, in fact one of the main gripes people had about CDs when they came out was that so many great covers couldn’t be appreciated in the same way. I find that’s pretty much the case when I’m browsing Amazon for books. Amazon thumbnail size is about 80 x 115 in pixels and that’s the image most of us see first. That being the case what we need are images that communicate when reduced to a fraction of their size. Here’s a good example:

Do you have any idea what the book might be about? Try this link.

There are a couple more tests that book covers need to pass:

The “yeah, right!” test is all to do with believability. Back in the sixties there was a trend in comics, at least in DC comics, where the cover lied. Take this one here

But the simple fact is that often the art on the cover bears no resemblance to the characters within the book. And the worst offenders there are probably fantasy and science fiction novels. Here’s the cover to C E Murphy’s Heart of Stone.

It's not that the art directors and artists and publishers are racist. But, by way of an example: a friend of mine -- a British fantasy author -- had the first book in her latest series bomb really badly on release in the US. Non-white protagonist, cover with representation of said protagonist ... publisher did the marketing right, but sales were inexplicably w-a-y down on what had been expected. The UK cover, in contrast, was a lot more abstract (as British covers currently tend to be) and sales were fine, on track with her previous novels.

The practice of “racebending” or “whitewashing” of covers is quite common it seems.

Here are three covers to the book Liar by Justine Larbalestier. The first is the Australian cover, the second is the first US cover and the last in the revised US cover.

Covers change how people read books

Liar is a book about a compulsive (possibly pathological) liar who is determined to stop lying but finds it much harder than she supposed. I worked very hard to make sure that the fundamentals of who Micah is were believable: that she’s a girl, that she’s a teenager, that she’s black, that she’s USian. One of the most upsetting impacts of the cover is that it’s led readers to question everything about Micah: If she doesn’t look anything like the girl on the cover maybe nothing she says is true. At which point the entire book, and all my hard work, crumbles.

No one in Australia has written to ask me if Micah is really black.

And in interview she said this:

RACEBENDING.COM: When the initial Liar cover was released, several bloggers—including industry professionals—spoke out against the cover design. You also spoke out against the cover design on your blog. How did the public outcry on the internet blogosphere lead to Bloomsbury changing the cover design?

Larbalestier: It definitely helped but there was a lot going on behind the scenes as well.RACEBENDING.COM: How has the Liar cover controversy impacted your writing?

Larbalestier: That’s a very difficult question to answer. I’ve been thinking about issues of race and representation for a very long time. What happened with my cover is not an isolated incident. A dear friend and mentor of mine, Samuel R. Delany, has been dealing with similar stuff since the 1960s with almost every book he’s ever written. I’d seen it happen to other people so it was strange going through it myself but I felt oddly prepared. I’m very pleased that many people who had not previously thought about race and publishing and representation now seem to have had their eyes opened.

The “so-what?” test has to do with whether what we see matters to us. So what if there’s a white girl on the cover and the book’s about a black girl? So what if the robot on the cover never appears in the book? A book cover to my mind should not be something that you need to get over. It should complement the text. You could also call this test, the “can-I-live-with-it?” test. There are books that I own that have awful covers but they’re good books. And so I’ve learned to live with the covers. Here’s an example, Robert Silverberg’s A Time of Changes:

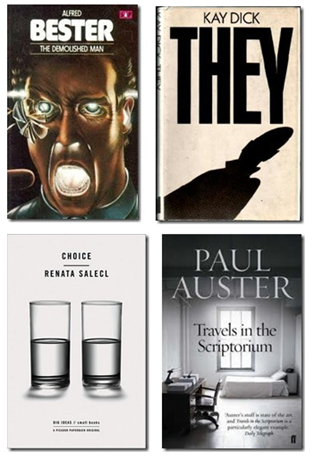

So what are my favourite covers? Can’t really write a piece like this without including one or two. Probably top of this list is this one by Adrian Chesterman, The Demolished Man. A great wraparound cover which I once saw as a poster in a wee shop in Edinburgh, never bought – couldn’t afford as I remember – and I’ve regretted it ever since. Here it is and a couple of others I liked.

So, how important do you think cover art should be?

Let me leave you with another slide show to ponder: the various faces of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

FOR FURTHER READING

Judging the Book: 50 Most Captivating Covers of All Time

Jerry Spinelli

Jerry Spinelli