If you have an important point to make, don't try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time - a tremendous whack. – Winston Churchill

I've received three books from Oneworld Classics up till now. This is the second I've got round to reading. They are all three beautifully produced, something that I think all publishers might need to keep in mind when they're asking people to fork out £7.99 for a copy; people are looking for value for money these days. So, what are we getting here?

- Preface to the 1832 Edition

- A Comedy About a Tragedy

- The Last Day of a Condemned Man

- Claude Gueux

This is a considered volume. The preface alone is 18 pages long and sets the tone. Its theme can be stated in a single sentence: Capital punishment is wrong. It's not a necessary evil and it has been allowed to exist because more fundamental social issues have not been attended to. There are only so many arguments though that you can use to support that assertion. And the young Victor Hugo uses them all. What you have to do is to try and imagine the world in which Hugo was writing. This is the France where public executions were something people, young and old, flocked to. They milked every moment for everything it was worth. An example, from the book's preface:

At Saint-Pol, straight after the execution of an arsonist called Louis Camus, a group of people wearing masks danced round the still-steaming scaffold. So, make examples. The Mardi Gras laughs in your face.

It's like any social issue. Take slavery in America. Let's say you were born into a world where slavery was accepted and all around you, would it not be hard to go against your indoctrination? And it's much the same with France and capital punishment. Slavery may have been abolished quite quickly in America but equal rights issues dragged on for years and years. In France the last public guillotining was of Eugène Weidmann, as late as 1939 – 110 years after Hugo first published his book – and the guillotine continued to be the official method of execution until the death penalty was abolished in 1981. The last actual guillotining in France was that of Hamida Djandoubi on 10 September 1977.

So, was Hugo wasting his time? Absolutely not. His was not the first voice to be raised in opposition to capital punishment. On Crimes and Punishments by Cesare Beccaria had been around since 1764 and had been widely read. Hugo's own writings on the subject would be translated into many languages and were the next rung on that ladder. He never lived to see the social changes he wrote about implemented but the fact is, in time, they were.

So, was Hugo wasting his time? Absolutely not. His was not the first voice to be raised in opposition to capital punishment. On Crimes and Punishments by Cesare Beccaria had been around since 1764 and had been widely read. Hugo's own writings on the subject would be translated into many languages and were the next rung on that ladder. He never lived to see the social changes he wrote about implemented but the fact is, in time, they were.

Why the book is still relevant is that, although France has now abolished capital punishment, the death penalty still exists and there is much debate about the humane methods used to end lives. The irony is that the guillotine was considered in its time a mercifully quick method of execution.

Preface to the 1832 Edition

This is the factual section of the book. In it Hugo reasons with people and provides examples to prove his belief that the effect of public executions are damaging to the very fabric of French society.

He talks about instances where simple executions have gone badly wrong. In one the blade fails to sever a man's head on its first go, the man screams in pain and the executioner raises the blade and lets it fall again only for the same to happen. Five times he does this and the man is still not dead. At this point, as Hugo puts it:

Infuriated, the people picked up stones and exercised their right by stoning the wretched headsman. The executioner took refuge under the guillotine and hid behind the police horses. But we aren't finished yet. Finding he was alone on the scaffold the victim got up from the plank and there, upright, horrifying, streaming with blood, supporting his half-removed head which was dangling on his shoulders, with feeble cries he asked for it to be cut off.

The executioner's assistant, "a young man of twenty" steps up to the plate "leaps onto his back and starts to cut through what was left of [the man's] neck with a butcher's knife."

But there is more. Apparently a judge should have been present who could have stopped this farce with a wave of his hand. But there was none. And there was no investigation afterwards.

Hugo claims that execution, particularly this form of public execution, debases everyone who comes in contact with it. Towards the end he has this to say:

The social structure of the past rested on three pillars: the priest, the king, the executioner. It is a long time now since a voice said: "The gods are dying!" Recently another voice cried out: "The kings are dying!" Now it is time for another voice to say: "The executioner is dying!"

Thus the old society will vanish stone by stone, and in this way destiny will complete the collapse of the past.

A Comedy About a Tragedy

This is a decidedly odd piece of writing. I actually came to it after reading everything else and that might be best because here Hugo is presenting a little play, no, a comedy sketch where we see a group gathered in a salon discussing the very book we're about to read:

SOMEONE: But why did he write it, this novel?

ELEGIAC POET: How should I know?

A PHILOSOPER: To campaign for the abolition of the death penalty apparently.

FAT GENTEMAN: A horror I tell you!

CHEVALIER: Absolutely! So it's a duel with the executioner?

ELEGIAC POET: He has a frightful grudge against the guillotine.

A THIN GENTLEMAN: I can see that from here. It's nothing but ranting.

FAT GENTLEMAN: Exactly. There are barely two pages about the death penalty in this text. All the rest is sensationalism

PHILOSOPHER: That's the problem. The subject merits logical discussion. A play, a novel, proves nothing.. And besides I've read the book, it's no good.

How about that? Yes, let's cut to the chase. Hugo's written his own bad review. The tone throughout is derisory. But, of course, by mocking himself and his cause he draws attention to it. This was actually the preface to the third edition of the book.

The thing we need to remember was that in 1829 Victor Hugo had still his greatest works ahead of him. The Last Day of a Condemned Man is really his first major work. The Hunchback of Notre Dame followed two years later but the world had to wait until 1862 for his masterpiece Les Misérables. So, he was known, but not well known.

The Last Day of a Condemned Man

Although this is called The Last Day of a Condemned Man it actually deals with the six weeks beforehand from his conviction, through his imprisonment awaiting the outcome of his appeal right down to the very moment of his execution. In practical terms much of the latter section could not have been written by him but Hugo exercises some poetic license here.

The book is presented as an account, a journal, written in the first person by a young, condemned man. In all his writing he never suggests for a moment that he is innocent or that there has been a miscarriage of justice. No. And I think it's important here that we realise that our unnamed protagonist is guilty of a capital offence. Hugo is not arguing for an innocent man's life here. That is not the point of the book. He is saying that the Old Testament mentality of "an eye for an eye" is outmoded. He is also saying is that the last few seconds of a condemned man's life are almost relief from the weeks of mental torment that he goes through.

They say it's nothing, that you don’t suffer, that it's a gentle end, that death is much simpler like that.

Oh yes? So what are these death throes that last for six weeks, this death rattle that lasts a whole day? What are the agonies of this irredeemable day that goes so slowly and yet so fast? What is this ladder of torment that ends at the scaffold?

Apparently that isn't suffering.

Surprisingly this section is far less graphic than the preface. It is a fine companion piece because it deals with the psychological aspects of the death sentence. The narration describes in detail exactly what happens to him from the moment sentence is passed until he finds himself standing on the scaffold about to be decapitated. We are spared the actual beheading itself. There are a number of references to actual criminals and officials that give the text a real world feel to it.

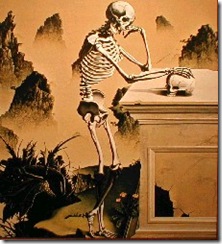

Mihály Munkácsy: The Last Day of a Condemned Man

It provides a fascinating insight into what goes through a man's mind once he knows he is going to die. Basically nothing else:

Whatever I do this hellish thought is always there, like a leaden ghost beside me, alone and jealous, driving all other distractions away, face to face with wretched me with its icy hands whenever I try and turn away or close my eyes. It creeps in everywhere my mind would like to escape to, mingles with every word that's spoken to me like an awful chorus, presses itself against the bars of my dungeon with me; haunts my waking, spies on my spasmodic sleep, appears in my dreams in the shape of a blade.

I didn't think there would be much to surprise me in this book. But there were things I didn't expect. The first was gallows humour (which I really should have anticipated), much of it from the condemned himself in the form or ironic asides; the second was how, despite the unpleasant conditions of the prison in general and in cell in particular, he is treated with both politeness and dignity; that I really didn't see coming. There are also moments of what I can only call farce. The first was his description of a new chain gang getting ready for the road. The second is when a gentleman in a hat, a junior architect, comes into his cell with a folding rule and begins measuring it. It seems the place is due for an upgrade. After he is done he comes over the condemned man and informs him:

"My dear fellow, in six months' time this prison will be much improved."

And his gesture seemed to add:

"It's a shame you won't get the benefit of it."

He was almost smiling. I thought I saw the moment coming when he would start to pull my leg gently, like you do a young bride on her wedding night.

My policeman, an old sweat with stripes, took it on himself to answer:

"Monsieur," he told him, "we don’t talk so loudly in a dead man's room."

The third is when a guard asks his to visit him after his death to tell him the winning lottery numbers.

But for me, and I imagine most people, the most heart-rending moment comes when a couple of hours before his execution he gets a visit from his three-year-old daughter. I have no doubt that many will have been reduced to tears by what happens in that short visit and I have no intention of spoiling it here. Yes, we know how the book is going to end. That is a foregone conclusion. But before his head is lopped off here his heart is torn out.

He goes though what you would expect. He wants to believe it's all a bad dream and where he realises it isn't he dreams instead of escape and of pardon. There is a glimmer of hope at one point, a chance to escape, but it is dashed and so he escapes instead into the past, to memories of better times and thoughts of his childhood. He looks to God for comfort but not being much of a believer he finds none there. As his end draws near he finally begs for more time. This is a book about a dying man's journey. It is all he has to leave the world. He makes a will but virtually everything he has will go to pay his costs. "The guillotine," he points out, "is expensive."

Dostoyevsky called the book a "masterpiece". It's not. But it's certainly the working notes for one.

Claude Gueux

Claude Gueux, an early example of "true crime" fiction, appeared in 1834, and was later considered by Hugo himself to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, Les Misérables. To my mind this is the most powerful of all the texts collected in this volume. Capital punishment is a side issue here however. What it is is a character study. And through his character's eyes Hugo let's us see how justice was meted out in nineteenth century France although frankly it reminded me of many modern tales of prison cruelty, particularly Cool Hand Luke because Luke is also imprisoned for a relatively minor offence (cutting the heads off parking meters one drunken night).

Claude Gueux is a man on the bottom rung of a society that has done him no favours. Although only thirty-six you might think he was fifty. He is uneducated, poor and starving. One day, pushed to breaking point, he steals a loaf of bread to feed his wife and child. But he is caught and sent to the Clairvaux Prison, once an old abbey. Gueux is a big man and needs more than the daily ration to sustain him. He is literally starving to death. Then one of his cellmates, a young and shy criminal named Albin, kindly offers to share his food with him. Albin is twenty-two but looks seventeen. This moves Gueux to tears and a close friendship develop between the two men, "more of a father-son relationship than brotherly."

Gueux is quite a different man from 'Cool Hand' Luke. He manages to be something of a model prisoner and also a man the prisoners look up to and will obey.

This authority came to him without him even thinking about it. It was due to the look in his eye. A man's eyes are a window through which we see thoughts coming and going inside his head.

Put a man with ideas among men who have none and, by some irresistible law of attraction, after a certain time all these darkened minds will gravitate humbly and adoringly towards the illuminated mind. Some men are iron and other magnets.

Several times he steps in and talks them down. This gets to the workshop manager, a man known only as M.M., "a gruff man, dictatorial, governed by his own ideas, constantly held in check by his sense of personal authority," who is jealous of Claude's innate ability to inspire friendship and obedience from all other prisoners. This is how Hugo puts it:

[T]o control the prisoners ten words from Claude were worth the same number of policemen. Claude had helped the manager out like this many times, so the manager cordially disliked him. He envied the thief. In his heart of hearts he harboured a private jealous, unrelenting hatred for Claude, the hatred of the rightful sovereign for the actual sovereign, of worldly power for spiritual power.

One day on a whim M.M. transfers Albin to another section of the prison as a way to demonstrate that he is still in charge. When Gueux asks why the only answer he is given is: "Because."

Gueux takes this very badly, and over the following months he repeatedly asks M.M. to bring back Albin to him but the man proves inflexible. Other prisoners offer to share their food with him but this has become a battle of wills between Gueux and the manager. One that has to come to a head.

This story really gripped my attention and although the narrator of The Last Day of a Condemned Man seems like a decent enough chap despite whatever he did to warrant his execution, Gueux is a good man pushed to breaking point. The prison drama reflects the social drama. Why did all of this come to a head? "Because," is the only answer we're given. It's a word used too often by adults to their children whose immediate response is: "It's not fair!"

In a lengthy epilogue to the story Hugo makes the point that there need to be fundamental changes in French society, that the criminal element is a symptom that can be cured rather than being lopped off. The last part of his speech is directly meant for the National Assembly of France of the French Second Republic, asking it to take action, to make the necessary social changes:

Gentlemen, too many heads are cut off every year in France. Since you are busy making economies, make one there. Since you are keen to axe jobs, axe the executioner. With what you save on eighty executioners you will be able to pay six hundred schoolmasters.

Think about the vast majority of the people. Schools for children, workshops for men. Did you know that of the countries of Europe, France has one of the lowest numbers of inhabitants who can read!

[…]

This head, the man of the people's head, cultivate it, till it, water it, fertilize it, shed light on it, give it virtue, make use of it, then you will have no need to cut it off.

Translation

This is a new translation by Christopher Moncrieff. He is an experienced translator and I've found a number of books he's worked on which have been praised by people who know a lot more about translating that me. His translation of Julien Parme's novel Florian Zeller was described by The Independent as a "stylish, street-smart translation" and I expect you could say the same about this one, just don't quote me.

There were a couple of things I did pick up however that seemed odd:

Meanwhile the coppers … quietly got on with their work. [CM Ch 13, p52]

Cependant les argousins … se mirent tranquillement à leur besogne. [French]

Meanwhile the galley warders quietly began their work. [1894 ed, trans Eugenia De B.]

An argousin is a low-ranking officer in charge of the surveillance of prisoners. It can also be a slang expression for a policeman. 'Coppers' is such a uniquely British expression that it seems out of place here. Simply 'guard' would probably have done. The book is not short of Notes on the Text. One here would have been in order.

Escorted by mounted police and ordinary bobbies on foot… [CM Ch14, p57]

…escortées de gendarmes à cheval et d'argousins à pied, [French]

…escorted by mounted gendarmes and guards on foot, [1894 ed, trans Eugenia De B.]

Here he's changed from 'coppers' to 'bobbies', again a very British expression. Also the French term gendarme is well enough known – the world is a much smaller place these days – so I don't see any reason not to use it rather than the more universal 'police'.

There's also a minor point in 'Claude Gueux' – he refers to the workshop manager as 'M.M.' but in the original French he is 'M.D.' and I can see no good reason to make the change. The text is available online in French and English. (My wife pointed out that in earlier translations the manager is referred to as the 'Director' and so 'M.D.' may mean 'Monsieur Director'.)

Overall the edition is quite readable and I didn't trip over anything else. Chapter 23 contains a lot of slang expressions which meant keeping a finger in the back of the book while I got through it but they're all explained.

Summary

I'm not sure about this book. I'm not sure who would want to read it. It's not a fun read, not that all reading should be fun, but I'm still not sure who, other than French history and literature students, would be especially interested in it. That said, I'm not one for reading historical fiction at the best of times so maybe I'm judging to book too harshly. Because it kept my interest. Especially 'Claude Gueux'.

I'm not sure about this book. I'm not sure who would want to read it. It's not a fun read, not that all reading should be fun, but I'm still not sure who, other than French history and literature students, would be especially interested in it. That said, I'm not one for reading historical fiction at the best of times so maybe I'm judging to book too harshly. Because it kept my interest. Especially 'Claude Gueux'.

I chose the Churchill quote deliberately. This is a pile driver of a book. Hugo makes his point and then makes it again and again. And by the end you are left in not the slightest doubt about how he felt.

Solaris

Solaris

![clip_image002[9] clip_image002[9]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/_kmVGrSP_9gU/SoKInUhBvSI/AAAAAAAABec/MuQFtq-2VM4/clip_image002%5B9%5D%5B3%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[10] clip_image002[10]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_kmVGrSP_9gU/SoKIn8rgToI/AAAAAAAABeg/wlae-h0mnEA/clip_image002%5B10%5D%5B3%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)