I first came across Richard Brautigan in Saltcoats about twenty years ago in an Ayrshire Cancer Support charity shop on Chapelwell Street. I mean his books and not the man since he’d been dead about seven years by then. I can’t be more precise and a greater degree of precision wouldn’t alter the basic facts. I found four novels by him and purchased three of them purely because I liked the covers, all of which featured a photo of him; I’d never heard of him before that day. The three I bought were In Watermelon Sugar, Willard and his Bowling Trophies: A Perverse Mystery and The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966. They were the Picador editions from the seventies. Since then I’ve bought A Confederate General From Big Sur in that edition but I don’t think that was the fourth book. I remember it as Trout Fishing in America but who’s to say I’m remembering correctly? I probably paid less than a pound for all three. Why I didn’t take all four I can’t tell you. Perhaps the cover to the fourth paperback was damaged. Suffice to say whatever book it was I’ve now acquired a copy and read it.

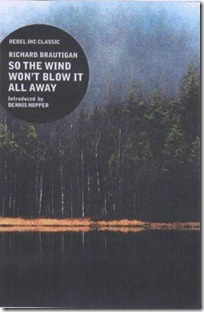

The fourth-to-last book I read by him was So the Wind Won’t Blow it all Away. After that I read my own copy of An Unfortunate Woman: A Journey and then Steve Kane lent me his omnibus edition which contained Dreaming of Babylon: A Detective Novel 1942 and The Hawkline Monster: A Gothic Romance along with a third novel I’d already read. Those were the last two books I needed to read to be able to say that I’d read all his novels, short stories and poems taking into account the provisos mentioned in my second paragraph.

I’ve just reread So the Wind Won’t Blow it all Away. I expect I’ll read it again before I die. In fact I expect I’ll reread all his books before I die (unless I die sooner than expected) although I might not reread Dreaming of Babylon and The Hawkline Monster because I’d have to locate fresh copies to do so. But you never know. It kinda bothers me that I don’t own all his novels.

When So the Wind Won’t Blow it all Away was published it was not exactly an occasion. It sold but only a modest 15,000 copies. This is what the review in Playboy opens with:

If you came of age in the late Sixties, Richard Brautigan was one of the staples in your pop-culture diet. He was the good angel on your shoulder, the counterculture's answer to Walter Cronkite. Today, we tend to greet the arrival of a new Brautigan work the way we greet the announcement of our 11th class reunion: nothing historic but nice enough if you can fit it into your calendar.[1]

It is unmistakably Brautigan. And I’ll be honest a little Brautigan can go a long way; he is like Beckett in that respect. His style is laconic, repetitive and expressed in the simple, straightforward language that poor people living on Welfare in any one of a thousand small towns will use happily turning nouns into verbs whenever it suits their needs. The setting in this book is a succession of dreary towns in Oregon but you could shift the action to Louisiana or South Dakota and not bat an eye.

The story is told by a forty-four-year-old man writing on 1st August 1979 looking back to when he was a boy. Most of the story concentrates on when he was twelve and thirteen but he does jump about a bit in fact the narrator’s quirky perception of time is one of the delights to this piece. The story itself – a fictionalised memoir – is quite straightforward but he tells the story as he remembers things and this necessitates leaps in time and breaks in the narrative. What he’s really doing is putting off saying what he has to say because no amount of context is going to change it or the effect what is going to happen / has happened has had / will have on his life. If you can picture a forty-four-year-old man looking back to when he was a twelve-year-old who’s looking forward to when he’ll be thirteen you’ve probably got the right kind of mindset for this book. Of course we remember things differently as we age. Here’s a good example:

[L]ooking back down upon that long-ago past now from the 1979 mountainside of this August afternoon, I think the ‘old man’ was younger than I am now. He was maybe thirty-five, nine years younger than I am now. To the marshy level of my human experience back then, he seemed to be very old, probably the equivalent of an eighty-year-old man to me now.

Also, drinking beer all the time didn’t make him look any younger.

It’s easy to read that, get the gist and pass on by but there is real poetry here; he’s describing life as a hill that we have to climb.

The ‘old man’ is just one of a number of characters that our narrator encounters between 1940 and 1948 but mostly in 1947. His days don’t amount to much, fishing in a manmade lake (created when they were building the overpass), cycling around on a bike so filthy you could no longer tell what colour it used to be or surveying his kingdom looking for beer bottles or worms – a penny apiece deposit for the bottles and the same per worm from the man who ostensibly ran the filling station but who seemed more interesting in procuring worms to sell to the fishermen who had to pass his premises on the way to fish than selling petrol. The area is surrounded by sawmills and agricultural land which the boy enjoys investigating including two “domesticated orchards that had been totally ignored, abandoned for reasons unknown and had reverted to the wild.” In one of these the apples are mostly rotten and the local boys like to go there and shoot them with their .22 rifles.

Needless to say, America has changed from those days of 1948. If you saw a twelve-year-old kid with a rifle standing in front of a filling station today, you’d call out the National Guard and probably with good provocation. The kid would be standing in the middle of a pile of bodies.

From now on … he was to sleep out in the garage. He could take his meals in the house and bathe and go to the toilet there, but those were the only times they wanted him in there.

To make sure that he got the point of their dislike, they did not provide him with a bed when they exiled him to the garage. That’s where I come in and the gun comes in.

The boy had a .22 calibre pump rifle. I had for some unknown reason, I can’t remember why, a mattress.

Following a brief discussion on how inclement a winter it was expected to be, the exchange is made. It is the first step in a sequence that climaxes on 17th February 1948. The next link in the chain takes place on 16th February 1948, a rainy Friday afternoon as it happens. In fact our narrator interrupts the story he’s been telling us up to this point (he’s drifted back to 1947 and is awaiting the imminent arrival at his pond of an overweight husband and wife team of fishers) and the action literally freezes in his head; he can’t not tell his tale any more. No, suddenly his mind has rewound the approximately “3,983,421 hours of film” in his head and he finds himself on a street faced with a decision:

I had a friend who liked to shoot apples … but he didn’t like to go to the junkyard to practice the little decisions of destruction that a .22 rifle can provide a kid. But I couldn’t shoot anything one way or another if I didn’t have any bullets.

Some bullets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . or a burger, a burger . . . . . . . . . . . . or some bullets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . paddled back and forth in my brain like a Ping-Pong ball.

The door to the restaurant opened just then and a satisfied customer came out with a burger-pleased smile on his face. The open door also allowed a gust of burger perfume to escape right into my nose.

I took a step toward the restaurant but then I heard in my mind the sound of a .22 bullet turning a rotten apple into instant rotten apple juice. It was a lot more dramatic than eating a burger. The door to the restaurant closed escorting the smell of cooking hamburgers back inside like an usher.

What will I do?

Needless to say he makes the wrong decision. And while his story remains frozen – the story of the pond, the old men and the couple who brought their whole living room in a truck to keep them company while they fished – he finally lets us know what happened in that orchard in 1948 before returning to 1979 where he has been sitting with his “ear pressed up against the past as if it was the wall of a house that no longer exists” and where he finally gets to finish reliving the previous memory and let it run on to its end. Is it the twelve-year-old boy that the couple find waiting for them or does he house the consciousness of the man full of regret and remorse that he will become? I couldn’t say. The couple set up their living room beside the lake, begin to cook their meal and the next thing they notice he’s vanished:

‘I don’t see him anywhere.’

‘I guess he’s gone.’

‘Maybe he went home.’

Who am I to say where ‘home’ was, the past or the present? Of course they’re all past now.

I was twelve in 1971. T-Rex and Slade had their first number ones. I didn’t have a .22 rifle and, if memory serves me right, my bike was blue. I probably did fire my first air pistol back then; before that it was water pistols and spud guns. Looking back on the history of that time it wasn’t that grand. The UK’s economy was in decline: there were constant strikes, the three-day week, electricity blackouts. My dad was never out of work but times were tough. And yet I do look back on that time and regret its passing because there was a lot lost back then that I don’t see us getting back. What I’m saying is that I can relate to what Brautigan’s getting at in this book. It’s not just about a mistake that a boy makes that affects the rest of his life because we all have those. We know from page one pretty much what’s going to happen. Brautigan drip feeds us details but if you’ve read the blurb on the back you’ll already know.

The book really isn’t in chapters but it is in sections and each one is divided by this:

So the Wind Won’t Blow It All Away

Dust . . . American . . . Dust

in italics.

The boy first realises his own mortality when he’s five and witnesses a child-sized casket being carried from the mortuary his family then lived over and this morbid preoccupation stays with him for several years. Later he learns about a boy who is killed in a car accident which both his parents survive. And a little while after this one of three daughters, a girl of about eight dies. He never sees her die – she dies of pneumonia – but the boy witnesses loss through the disappearance of toys from once-littered lawns and porches:

Her living sisters were afraid of their own toys because they didn’t know what toys had belonged to the dead girl and they didn’t want to play with the toys of somebody who was dead. They had played so freely and intensely that they could not separate the toys of the living from the toys of the dead.

These events foreshadow the climactic event of the boy’s life, the death that marks the end of his childhood. Symbolically, Brautigan is also looking back on what he sees as America's age of innocence. The adults that he talks about – with perhaps the singular example of his mother and her obsessive fear of gas leaks – may have been impoverished but nevertheless they seemed content with simple pleasures:

In those days people made their own imagination, like homecooking. Now our dreams are just any street in America lined with franchise restaurants, I sometimes think that even our digestion is a soundtrack recorded by Hollywood by the television networks.

I can draw an English comparison: Pooh Bear. Yes, I know it’s a children’s story but it’s set in a very real childhood. There’s a scene in Brautigan’s book where the guy who looks after the filling station asks one of the boys if he wants a bottle of pop:

‘No, I’ll wait for summer,’ David said.

‘OK,’ the old man said. ‘Suit yourself.’

He went back into the filling station to wait for summer.

Is that really any different to Pooh:

Sometimes I sits and thinks, and sometimes I just sits.

That world has vanished too. As has the world of The Famous Five and Swallows and Amazons. But the books remain and it’ll be a while before they turn to dust.

Although he never confirmed or denied the connection, the story was thought to be autobiographical, built on an incident that happened to Brautigan at age thirteen.

Actually, the story was created from two separate incidents. The first involved Brautigan, his best friend Pete Webster, and Pete's brother, Danny. The three were duck hunting in the Fern Ridge wetlands, near Eugene, Oregon. Brautigan was separated from the other two. Brautigan fired at a duck and a pellet from his shot struck Danny in the ear, injuring him only slightly. About the same time, Donald Husband, 14-year-old son of a prominent Eugene attorney, was shot and killed in a hunting accident off Bailey Hill Road. Brautigan's incident and that involving Husband became one in this novel (Bob Keefer and Quail Dawning 2H).[3]

FURTHER READING

REFERENCES

[2] Ianthe Brautigan, You Can’t Catch Death – A Daughter’s Memoir, p.viii

[3] richardbrautigan.net

22 comments:

This post resonates for me, jim. I'm one who's never read Brautigan and now I think I will. Needless to say - to you at least - I enjoy 'autobiographical fiction'. I enjoy the weave of so-called reality, the way things happened in memory and the way they are imagined and reflect on how they re now.

Those words, 'his ear pressed up against the wall of the past,' are stunning. I think it describes so many of us. i also enjoy the few short references to your memories of this time in your life.

Readers can be cruel. Their expectations impossibly high. It saddens me to think that Brautigan for all his wonderful writing may have felt shunned in the end.

And the idea that he should kill himself with a rifle seems to be hinted at in his writing and the earlier incidents you describe here from his life.

This is such a sad story and yet Brautigan leaves behind such treasures.

Thanks, Jim, as ever for a terrific review.

This was a wonderful review. I've never read Brautigan, but now I have to. Tour own writing is stunning.

That was meant to read: "Your own writing . . . ."

I have most of Brautigan; not all the novels, but all the poem books. I find I like him best in small doses, like with the poems. I was never as big a fan as some friends of mine, but then, I was also never really a hippy. I missed the Beatles and Woodstock by being just slightly too young. Still I like his writing.

I think Brautigan did feel shunned in the end; but I'm not sure if he was, or how much of that was in his own head. When I get depressed, the one thing the bad voices say over and over again is that no one understands, or cares. So I can certainly understand his last choice, although I also understand that it was probably a wrong one.

I was introduced to Brautigan poems as a boy and had that thought so many have about contemporary poetry: What Makes This a Poem?

After a few years and a much better introduction to poetry than I'd gotten out of textbooks - a Poets-in-the-Schools program brought two poets to school - I learned that poetry didn't have to be about counting (I was never much for math) but about what language itself wanted to do.

I discovered Brautigan anew. In college I set out to read everything by him. Didn't quite succeed, but got to most of it. Favorites have to be "Trout Fishing in American" and "The Tokyo-Montana Express"; both are more like collections of prose poems than novels. I learned I loved his poems, too.

It amuses me to think I could write a screenplay for "Trout Fishing" ... a challenge!

Brautigan's genre novels didn't seem to me particularly successful, but as the line you quote about the scent of burger being guided back inside the restaurant as though by an usher proves, Brautigan provides pleasures other than plot.

I'm sure Brautigan knew depression all his life. Fame burst upon him in a way that would have shocked anyone. He tried to ride it out with the same gentle good humor and openness you see in his writing. I'm not surprised that didn't work. Unlike Kurt Cobain Richard Brautigan did not kill himself at the height of his fame, but after the fame had all but receded. If he were still alive he would be drawing crowds. If he still wanted them.

Most of Brautigan’s fiction isn’t autobiographical in nature, Lis, although, like all of us, autobiographical elements do crop up but not as much as some. He has a voice that permeates all the books—you really know within a paragraph or two that you’re reading Brautigan—he was fairly adventurous and didn’t write the same book over and over again. This also means that some of his books are less successful than others but he’s never less than readable and none of his books are long in fact I bet most of them clock in as novellas; they feel weightier but there’s usually quite a bit of white paper as his chapters are often extremely short, a page or less on occasion. He is a poet through and through and even though his prose isn’t poetic in the same way as, say, Elizabeth Smart’s is, his writing is exceedingly metaphorical and evocative. Here’s an excerpt from The Abortion:

She was wearing a blue sweater and skirt and a pair of black leather boots in the style of this time. She had a fantastically full and developed body under her clothes that would have made the movie stars and beauty queens and showgirls bitterly ooze dead make-up in envy.

She was developed to the most extreme of Western man’s desire in this century for women to look: the large breasts, the tiny waist, the large hips, the long Playboy furniture legs.

She was so beautiful that the advertising people would have made her into a national park if they would have gotten their hands on her.

Then her blue eyes swirled like a tide pool and she started crying.

I can never settle on a favourite book but this one is always up there. I just loved the idea of a library that accepted books by everybody and anybody; you could just ring the bell, day or night, and you would be welcomed in and invited to leave your book on any shelf that felt right to you.

Elizabeth, I’m glad you enjoyed my review. I hope you also checked out the other article I wrote, Richard Brautigan, my mum and I.

Something you’ve not read, Art! I am shocked. No, in all seriousness, I’m surprised to find you’ve not read everything by him. At the rate you read you could probably gobble down all the novels in a day. That said you are right in suggesting that he’s best appreciated in small doses. I was ten when Woodstock was happening and although I was aware of the existence of The Beatles I never really discovered them until I was quite a bit older; I wasn’t really into pop music at that age. I joke that my wife was a hippy—she’s twelve years older than me—but, despite having a hippy van, I think she was more army brat than dyed in the wool hippy.

Suicide is a fascinating subject, Glenn, and I think I might try and research it when I’ve a minute (I’m behind on book blogs at the moment so it’ll have to wait till I’m caught up). Who knows why anyone decides enough is enough. It’s a little sad in his case—not that all suicides are not sad in their own way—because, as you say, the worst of it was over and he could have slipped off into semi-obscurity. I’m not remotely famous but through being online I am now acutely aware of people’s attention and, to be honest, I even find having a handful of people out there with any kind of vague expectation a burden. You feel you’re answerable to them and he must have felt the same only in his case people’s tastes moved on but he didn’t and the reviews reflected that. Only years later was he rediscovered. And how many artists and writers has that happened to?

Oh, well, suicide. That's a subject I know only too well. What intrigues me is that the culture still carries lingering stereotypes about the Tormented or Starving Artist, and so when a writer suicides we all say it's sad, but everyone seems to be slightly relishing the event as inevitable. Like when you drive by an awful accident on the highway. Artist suicides are in a special class of suicides. And of course there's the whole thing about great writers having to drink themselves to death.

I always remember what Rilke said, when it was offered to him to engage with psychotherapy. "I'm sure that it would relieve my demons, but I'm afraid it would offend my angels." So there's also that whole pattern of artists choosing to stay suffering with their art, rather than find relief. Having done a bit of therapy here and there, I've found that in fact feeling better about life made me more productive rather than less. Albeit I can still write a dark poem on a bad day. (Yesterday, for example.) One adds layers to experience, rather than removing them.

I recently borrowed 4 Richard Brautigam books from my local library. Two of them I couldn't get into. Not that the pages were glued together or anything like that. Just that I wasn't in the right mood or frame of mind perhaps. But I enjoyed, if you can enjoy it, the Hawkline Monster. And I also enjoyed the one about the hat that lands in a town square and starts a riot. I got stuck early on, or maybe I fell off the hook, in Trout Fishing . . . but will definitely take another bite.

That’s exactly it, Art, and why I’ve added the subject to my list of things to get around to researching eventually. I don’t feel like a cliché and I’m sure you don’t and yet, and this is the perverse thing, a part of me would dearly love to become a stereotypical writer because at least they get to write and have readers, the ones who aren’t permanently blocked anyway. I’ve never seriously considered suicide. As a writer I’ve considered it but I’m not sure I’ve ever tackled the subject even in a poem. But I think it might make an interesting blog looking at why writers decided to end their lives prematurely. I’m not even sure how many I’ll find but it’s on the backburner. I’ve pasted your comment into my notes because you make a couple of good points that will get me started.

And, Gwilliam, it took me a while to get round to Trout Fishing in America. I imagine it’s the best known but there was something about it that just didn’t call out to me; the title I suspect because I also dragged my feet getting round to A Confederate General From Big Sur because the title does nothing for me. Actually none of his titles are really that inspiring apart from In Watermelon Sugar which was the first book I read. (I think: one can never completely trust my memory of anything these days.)

I don’t really see him as a writer one has to persist at. If you’re not getting into him then the best thing is to put him aside until you’re in the right frame of mind. What saddens me is that I’ve read him all now and I have to sit around waiting until I’ve forgotten enough to make rereading him enjoyable enough to bother. That said, as I’ve suggested, that’s taking less and less time these days.

I haven't read Brautigan in years, although I never stopped admiring him. My tastes are more refined now than they were in my dissolute, misspent youth, and I've wondered whether I would still like him, like him more, or less. I'm glad to see you've posted about him. His plainness and simplicity are a rebuke to more mannered and showy writing, and I'm glad to see it holding up in your estimation.

Big books are definitely in, Wolf, some of them longer than Brautigan’s entire output. They weary me. One of the first thing I check when I’m offered books for review is how many pages am I going to have to wade through. I’ve never done that with a Brautigan. As for whether you’d still like him, who can tell? Methinks you would. It’s been over twenty years since I first read him—and I’d already left childish things aside by then—but when I finally got round to the last couple of novels a few years back it felt good to have more to read and I’m a little sad that I gobbled down those last two books because there was no more new stuff. If you do chance upon him in a bookshop try this one. Everyone goes for the earlier stuff but I enjoyed his last two published books, the one I’ve reviewed here, and An Unfortunate Woman which was published posthumously. There is still an unpublished ‘novel’ (I use the term loosely as it’s only 600 words long even though there are twenty chapters) called The God of the Martians which was supposed to be being published by an Australian firm but I can find no trace of it seeing the light of day.

I've just emailed you, saying that I wouldn't, and come straight over and done it anyway. You can't believe a word I say!

And what happens? You make the damned book sound so attractive, I know i'll end up buying it!

My wife says she always can tell when I'm passionate about a book, Dave. I like getting the free books to review and there are always a few decent ones - but there are so few that really excite me. Not like this bloke.

Haven't read Richard Brautigan but will have to now. I did however read the whole of the Malloy/Malone Beckett trilogy gradually as bedtime reading over about a year.

Sue, Brautigan’s so unlike Beckett it’s not true. But I can appreciate the two of them. The only real similarity is that, towards the end of his career, Beckett favoured more and more compressed forms of expression; Brautigan was never remotely long-winded even as a young writer. I’m impressed you’d tackle the Trilogy at bedtime though. I’ve read it but during the day and with a clear head.

As in the Playboy characterisation of Brautigan's early readers, I tried him in the late '60s and simply couldn't get on board. I was still high on the amphetamine prose of the Beats and that low-key, demotic style didn't do it for me at all. But you and Ianthe have persuaded me to pull out 'Trout Fishing...' again for a second look.

You know I find that most strange, Dick. You clearly have a great love of the metaphor. I would have thought you would have lapped up Brautigan. Let’s hope that your reinvestigation is a pleasant one.

Dear Jim, very engaging post. Talking about impressive and unique novelists I would like to know if you have read the unique, monumental, exhuberant "Infinite Jest" by David Foster Wallace who committed suicide in 2008.

A post of yours on "Infinite Jest" I am sure would be a delight!

Davide

(Tommaso Gervasutti)

After struggling through The Instructions, which clocks in at 1030 words, Davide, I swore I would never read another novel of that length and so, at 1079 page, I’m afraid that David Foster Wallace’s tome is on a hiding to nothing. Sorry.

Well, I admit Infinite Jest is a very difficult and chaotic novel but in some parts is so deep for me, hilarious and utterly exhuberant, a delight.

Jim, I have written some, very few, reflections on rhymes and rhyming in my blog. I would be glad to hear your opinion on it.

By the way I am sure that a ppst of yours on this issue would be very engaging.

Jim, I'm happy to see yet another point we have in common: I LOVE Brautigan, ever since I first picked up In Watermelon Sugar back in the 70s. But I didn't read a lot of his work until the 90s, and still haven't read it all. One of my all time favorite short stories is his "1/3, 1/3, 1/3."

I will have a look at your post, Davide. I have, of course, thought about writing a post about the 21st century poet’s relationship to rhyme (and metre too since for a long time the two were inseparable) and maybe I will one day. I have a book review coming up on the subject of creativity where the author makes an interesting case for the benefits of writing more structured poetry so watch out for that. I think it’ll be the next post up.

And, Brent, yes, the short stories. I’ve never written about them and maybe I should. It was no surprise to find that his stories and poems were every bit as delightful as his novels because one might argue that some of his novels—I’m thinking specifically of Willard and his Bowling Trophies—feel like short story collections with those tiny, self-contained chapters and his prose is just filled with poetry. I’m sure that’s what I love about this guy more than anything, the fact that he sees no distinction between poetry and prose; one flows into the other and back again seamlessly.

Post a Comment