What we've got here is a failure to communicate. – Cool Hand Luke

Things being the way they are I would imagine Sam Shepard is best known by most people as an actor – the Internet Movie Database lists a respectable 56 entries for him spanning 5 decades including a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of pilot Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff – but his real claim to fame is as a playwright for which he received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1979 for his play Buried Child; he’s written almost as many plays as he’s had film roles. Not content with that he has also branched off into novels, memoirs, essays and collections of short stories. His third short story collection has just been published but I thought I’d have a look at his second, Great Dream of Heaven, which was published in 2002 and has been lying on my to-read shelf for a good couple of years now.

Carole Cadwalladr, who interviewed him in March 2010, describes him well:

If you had to invent an all-American literary hero, he'd be something like Sam Shepard. With his slow, western drawl, and his love of the open road and the empty badlands way out west, he's always seemed like the authentic voice of a certain sort of American manhood; telling stories – of suffocating families and wretched lovers – from the forgotten, inbetween places of the American outback.[1]

When I read that what jumped to mind was Arthur Miller’s The Misfits. I could even see Shepard stepping into the Clark Gable role if they ever decided to remake the thing. In the eighteen stories that make up Great Dream of Heaven three revolve around horses. (Shepard owns a horse farm in Midway, Kentucky and is passionate about them.) Also The Misfits was set in Reno in the Southwest of America and that’s where Shepard grew up:

All over the Southwest, really—Cucamonga, Duarte, California, Texas, New Mexico. My dad was a pilot in the air force. After the war he got a Fulbright fellowship, spent a little time in Colombia, then taught high-school Spanish. He kind of moved us from place to place.[2]

Although he has homes in New York and the ranch in Kentucky he still keeps a place in New Mexico.

His upbringing clearly did a lot to shape him as a man and subsequently as a writer. His father was an alcoholic (from a long line of alcoholics) with whom he had a difficult relationship. Needless to say in his own time Shepard has struggled with the bottle. In 2009 he was arrested for driving under the influence and ordered to attend an alcohol rehabilitation programme. He is routinely described as ‘taciturn’ and ‘private,’ “closer to the laconic and inarticulate men of his plays than to his movie roles.”[3] The irony is that he’s famous for the length of his monologues so I was curious to see how theatrical his short stories were, written, as one might expect, on an old manual typewriter; he has a mobile phone but refuses to even look at the Internet. Two reviewers[4] have called his short stories “one act plays masquerading as fiction” (one talking about this collection and the other talking about Cruising Paradise) and that’s a fair comment. If there were more internal monologues in the collection I might try to argue the other way but I can’t.

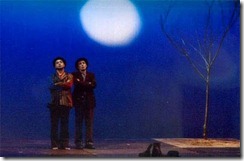

The pivotal moment in his life came on reading Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. At that point he decided he wanted to become a playwright and his “greatest literary regret” he says is that he never met Beckett. Shepard's early plays show absurdist influences but he’s come a long way since then and he’s read a great deal more. Calling him “[a] kind of cowboy Samuel Beckett”[5] or even suggesting that in his old age he’s starting to look a bit like his hero are things that would not displease

There are eighteen stories in this collection which, at 139 pages, is not long. They are in the style of vignettes, character studies, slices of life, scenes snipped from larger works and saved from the cutting room floor if you like; two of the stories are completely in dialogue. So if you need your stories to have a beginning, a middle, an end and maybe a nice moral tossed in for good luck then these are probably not for you.

Me? I loved them. It wasn’t the Beckett connection – I discovered all that afterwards – but this is exactly the kind of short fiction I enjoy. The descriptions are minimal, the writing is tight – he says what he has to say and gets off the page. I read the book in three sessions and that’s probably fast enough.

The first story, ‘The Remedy Man’ (which you can read in full here) is perhaps the most traditional story. It probably has more in common with Steinbeck than Beckett. It was also the one I liked the least although I certainly didn’t hate it. Put it this way, if I knew what I knew now about Shepard’s life before I read it and someone asked me, “Who do think wrote that?” I would say, “Sam Shepard” without batting an eye. The narrator is someone remembering an incident when he was a fourteen-year-old boy, the day E.V., “a springy little man in his late fifties with an exaggerated limp from having his kneecap crushed in a shoeing accident” arrives in his beat-up ’54 Chevy half ton to help tame a horse:

[H]e was not a horse whisperer by any stretch. He was a remedy man. He could fix bad horses and when he fixed them they stayed fixed. That’s all he laid claim to.

We never learn the boy’s name nor where this happens but it’s probably somewhere in California – Sonoma and Oakdale are mentioned in passing as being local destinations – not that that’s very important. The imagery is a bit heavy-handed and obvious and it really said nothing particularly new at the end, nothing I didn’t expect it to say. The boy’s going to leave. We leave him at the end hanging from the rubber inner tube that E.V. brought with him and the boy tied to a tree for him. He hangs there while his father calls him from the house:

I just hung there spinning in silence. I knew right then where I’d come from and how far I’d be going.

The image of someone hanging, dangling, is one that permeates the book. Okay the boy is literally hanging but so is the man in the second story, ‘Coalinga ½ Way’ in which a man leaves his wife without thinking things through properly and because of that the story ends with him asking pathetically:

“Where am I supposed to go?”

Again as readers we’re left not knowing what will become of the protagonist. We can guess. I expect he ends up going back to his wife with his tail between his legs but who knows. This is a minimal tale in more ways than one. It’s not simply a tale told in a few words; very little actually happens. The bulk of the story is taken up in two phone conversations, one with his wife, to let her know he’s left, and one with his lover, to let her know he’s arrived. The sentences are short on the whole and even those that aren’t are broken up by commas and semicolons so that they feel short:

“It’s time to make the call.” It comes to him like a voice; a command. If he doesn’t make it now, he never will. Dread or no dread, it’s time to make the call. He swings out and slams the door of the Dodge. The sound doesn’t carry. It ends abruptly at his feet.

There are other women he talks to, the operators, “female voices, different ages, each one completely devoid of sexuality.” The only other women we read about are those he sees in the stretch limos once he reaches L.A. and they’re every bit as distant as the others. The woman I called his lover earlier is actually only referred to in the text as “[t]he voice he’s become convinced he can’t live without” – there’s no clear indication that they’ve ever even met. Have they? By this point in the story I’m ready to read the whole thing again to see what I might have missed. In that respect this story has a lot in common with Beckett: it’s easy to read the thing and get the gist but miss the point.

Minimal stories tend to skimp on descriptions. Much as I’m in favour of that descriptions can be made to pull double-duty: they describe both the location and also the state of mind of the protagonist: what jumps out at him says a great deal about it. For example in Coalinga (which is in Fresno County, California by the way) this is what the man sees:

Beyond the phone [booth], pathetic groups of steers stand on tall black mounds of their own shit, waiting for slaughter. Heat vapours rise from their mounds, cooking under the intense sun as though about ready to explode and send dismembered cow parts flying into the highway. Beyond the cattle there’s nothing. Absolutely nothing moves, clear to the smoky gray horizon.

and when he arrives at the Tropicana in L.A.:

The hotel logo, a red neon palm tree, dances its reflection in the deep end [of the pool]. A fat man wearing a black Speedo sits perched at the top of the water slide, staring down at his toes. He wriggles them as though testing for signs of life. A TV goes on in a room across the pool deck. Someone pulls their curtains shut.

I fully expected that Shepard’s dialogue would ring true and it does, in every story.

‘The Blinking Eye’ is a road movie for one, sort of. A woman is driving across Utah towards Green Bay on the east coast for her mother’s funeral. Her mother is in the car with her. In the urn in the seat beside her that is. That’s no problem. She talks to her anyway:

She’s glad she finally has this time alone with her mother and she speaks to the tall green urn … in a voice exactly like the one she used when her mother was living. She speaks out loud while her bright eyes scan the enormous white sea of salt.

“I don’t know, Mom – I thought that check was for me. I mean, I honestly did. I never would’ve cashed it otherwise. Now Sally’s all pissed – outraged, like I’ve stolen something from her, committed some horrible crime behind her back. She gets so violent with me sometimes. You’ve never seen her get like that but she does. … Now she’s going to be at the funeral and I’ve got to go through this whole thing all over again with her. This whole routine. She won’t give it up.

‘Betty’s Cats’ is one of two stories in the collection that consists solely of dialogue. It differs from the other, ‘It Wasn’t Proust’ in that the latter story has a few what amount to stage directions. All we have in ‘Betty’s Cats’ is Betty and yet another unnamed character who I read as one of her two most likely younger sisters but in truth even the gender of the second speaker is not revealed. If you imagine Betty as the actress Betty White and Bea Arthur as the other then you have the idea:

Now Betty, how are we going to address this situation?

What’s the problem?

The cats, Betty.

That’s not my problem.

It’s our problem, Betty. They’re going to confiscate your trailer again if you don’t do something about it.

They can’t confiscate my trailer.

They did it once already.

Well they won’t do it again.

Betty – They’ve given you notice. If you don’t get rid of the cats they’re going to take your trailer away, It’s as simple as that. I don’t want to see that happen again. I mean where are you going to go, Betty?

I’ll find something.

And so we go on for another ten pages of trying to reason with Betty who, although the text never says, probably wears purple with a red hat that doesn't go, and doesn't suit her. Trailer parks exist the world over – we in the UK call them caravan sites – and so do ‘cat women’; there’s really nothing in this story that’s uniquely American. A delightful character study nevertheless.

There are a couple of very short pieces in the collection: ‘Foreigners’ is less than two pages long and ‘Convulsion’ is even shorter than that. Both have first person narrators and have the feel of little monologues. In the first a café owner talks about his attitude to his fellow Americans, how he treats easterners like tourists and how on a trip to Santa Fe he and his wife were made to feel like foreigners in their own country. I suppose non-Americans sometimes forget just how big the USA is – it might be a country but it’s a country that’s as big as a continent.

I think the two most interesting stories for me were ‘Living the Sign’ and ‘An Unfair Question’. They both involve confrontations but then there’s a lot of confrontation in this book; conflict makes good drama. Both reminded me of Pinter but that’s more to do with the setting than anything else. In the first story someone has put up a sign in a fast food restaurant and gone to some pains to hang it so that it’s at eyelevel and anyone standing at the counter can see it. It reads, in Magic Marker:

LIFE IS WHAT’S HAPPENING TO YOU WHILE YOU’RE MAKING PLANS FOR SOMETHING ELSE

It’s a quote from John Lennon from his 1980 album Double Fantasy. The story doesn’t tell you that. I’m telling you that. Knowing that isn’t important. You’ll get the story without knowing that, but I just thought I’d mention it.

“Who wrote that sign right there, hanging over the chicken?”

“I have no idea,” she says, even more peeved that I’m demanding her attention beyond the call of duty.

“I’d like to meet him.”

“Who?” she says in disbelief.

“Whoever wrote the sign.”

“I don’t know who wrote the sign,” she whines.

“Does anybody here know?”

Eventually a kid with a pulled-down cap from under which his ears protrude owns up and finds himself being interrogated: What does it mean? Did he make it up? Why did he feel the need to even put up the notice in the first place? It’s not as aggressive or menacing as The Birthday Party for example but this is a guy who’s ended up working in a fast food restaurant, who dreams about watching it snow in Colorado and has never given his actions that much thought. When the man asks, “Who wrote that sign?” he’s not looking so much for who came up with the words in the first place – he may already know – but he wants to know why someone felt the need to pass on those wise words of wisdom. Towards the end of their conversation he says to the kid:

[Y]ou wrote it down. You cut that little piece of cardboard very carefully and found a Magic Marker and wrote all the words down in capital letters. Then you covered the whole thing with strips of invisible tape so the words wouldn’t get splattered with chicken grease and you punched that little hole in the top and threaded that shoelace through it and then you climbed up there, above the wings, balancing and manoeuvring you fingers through the electric wires, tying the knot so that it would hang dead centre just below the lamps in plain sight of anyone who might come in, right at eye level where you knew the eye would be seduced into reading it and the mind would then turn it over, replacing for just a second and thought about food or hunger with a new thought that might turn them toward the actual plain fact of living and away from dreaming about the stock market or their girlfriend or their failed marriage or their history grades or even Armageddon. And in that flashing moment some mysterious light explodes through their whole body, sending signals to a remote part of themselves that suddenly remembers being born and just as certainly knows it’s bound to die. You did that…

‘An Unfair Question’ on the other hand is menacing. Enclosed spaces are at the best of times. Being in one with a bloke with a gun and a bit of an attitude is another thing. It is a story of two halves; in fact with very little rejigging they could stand as separate stories. Why they work better as one is because we know the guy in the first half searching for basil for his wife’s party in an almost empty supermarket only to return home empty-handed to learn that she’d had some all along is the same guy who ends up scaring the bejesus out of one of his wife’s guests, a woman he believes is from Montana and who makes the mistake of asking his advice on purchasing a firearm, in the second half.

There are very few couples in these stories and those there are are odd at best and strained at worst. In two of the stories, ‘The Door to Women’ and the title story, ‘Great Dream of Heaven’ the couples living together are men; in the first, a old man and his grandson, in the second two old men whose wives have died. On the surface both relationships seem sound but as the stories progress you realise that that’s not really the case.

Most of the stories focus on the individual and just how isolated people can find themselves. The blurb on the back says:

In these … stories, Sam Shepherd taps the same wellspring that has made him one of America's most acclaimed playwrights; sex and regret; the yearning for a frontier that has been subdivided out of existence and the anxious gulf that separates men and women.

There’s no sex, no sexual congress of any kind, but there is frustration and not merely sexual although if I was being flippant I might suggest that what most of these people need is to get laid. If there is a single theme to the whole work it is an inability to communicate. Some, like the couple in ‘It Wasn’t Proust’ still try though:

The one reading Proust?

It wasn’t Proust!

Just kidding.

I don’t know what it was but it wasn’t Proust.

Take it easy.

I can’t tell you anything without some underlying –

What? Some underlying what?

(They both go silent. A sharp wind creates a rippling line of surf like a miniature tidal wave heading straight toward them. Neither of them acknowledges the unaccountable terror it sparks in them. The man continues his tale but now it’s more like he’s talking to himself or maybe the reflections of puffy clouds racing across the lake.)

I enjoyed this book. Collections like this can sometimes be a mixed bag but these stories hang well together. It felt American but not the bold and brassy America we foreigners tend to think the whole country is like. In the old days the West represented the American dream. “Go West, Young Man,” was once the war cry. Now that dream had deteriorated, crumbled away. Old frontier landscapes and ideals have given way to shopping malls and suburban malaise. There’s nowhere to run. All that’s left is to turn around and look reality squarely in the face. Violence is a word that gets associated with many of Shepard’s earlier works but these are not

For the man who was once so inspired by Beckett’s Waiting for Godot which as you know ends with the two tramps saying they’re going to go and yet don’t move a muscle, it’s notable how many of these stories also end with the characters unable to move, to make progress: "He stays like that" (‘The Stout of Heart’); "I have no plans" (‘Living the Sign’); "There's nothing to do" (‘Betty's Cats’) and "I watched them very closely but they never moved at all." (‘Concepción’). This is more than a snapshot of America. This is America in stasis – the stillest of lives. Dead still in fact.

The evocative cover of the book is actually a family photograph showing Sam and his son Walker. It was taken by his partner, the actress Jessica Lange.

REFERENCES

[1] Carole Cadwalladr, ‘Sam Shepard opens up’, The Guardian, 21st March 2010

[2] ‘Sam Shepard, The Art of Theatre No. 12’, The Paris Review, Spring 1997, No.142

[3] Ibid

[4] Ben Fowlkes on Goodreads and Sarah Aswell quotes her friend Ben (who may well be the same Ben) on her blog.

[5] Michael Astor, ‘Sam Shepard's Day Out of Days offers glimpses of cowboy Beckett in era of the cell phone’, Washington Examiner, 11th January 2010

12 comments:

What a post! I fell head over heels in love way back in the 70s after seeing 'Days of Heaven.' He and lovely wife Jessica lived in Stillwater, MN during the years I lived in Minneapolis ... hoped for a sighting, never got one. He is so incredibly talented. Bob Dylan, another Minnesota boy and Sam collaborating on music .. oh boy!!!

A beautiful post so thank you for it.

Sam Shepard is one of my favorite writers. I have most of his books, just as I have most of Beckett, and enjoy them immensely. "Cruising Paradise" is another favorite. I like the style and tone of his language.

If more of American fiction was like this, instead of being overblown, narcissistic and frequently overwritten, I might like it all more. But in fact, Shepard's voice is almost unique. It's a grand, spare voice. As someone who has spent a lot of time out West myself, including living in New Mexico and California, I can affirm that it is a voice very suited to its landscape.

Thank you for this wonderfully literate post. I'm fascinated by the distinctiveness and the inter-relatedness of different genres. You provide insightful analysis on these relationships. I have (almost) made the decision that my next venture as a writer will be to try my hand at short stories (my most recent works are a memoir "August Farewell" and a novel "Searching for Gilead".) In preparation for plunging into the deep end, I'm reading a lot of other short story writers. Sam Shepard is now on my list thanks to you. David G. Hallman http://DavidGHallman.com

When I bought the book originally, Helen, I knew that he was an actor but I had him mixed up in my head with Sam Waterston who I knew for his work with Woody Allen. I don’t think I’ve ever seen Days of Heaven in fact on checking his appearances in front of the camera I see I’ve seen very few films in which he’s appeared. And here I thought I watched a lot of films. Guess not.

seymourblogger, thank you for saying that. I actually wrote this months ago and it kept getting overlooked.

I’m probably not the best judge of American fiction, Art. I don’t avoid it but there are great gaps, people I feel I ought to have read like Roth, Updike and Carver that I never seem to get round to. Not that there aren’t plenty of Brits that I’ve neglected. I would happily read this guy again though.

And, David, I came late to the short story format. I was stuck in the middle of my third novel and got an idea for a collection of stories based around a single idea, that of the senses—the other senses, sense of humour, sense of justice etc—and the next thing I knew I’d written about forty of them and was ready to get back into my novel. I am of the opinion that content dictates form. For my first twenty years as a writer I wrote nothing but poetry and then one day, after a three year long blank spell, I sat down and wrote two novels back to back. I never planned to. In fact when I was writing the first I didn’t even realise that what I was writing was a novel, just a very long story so I thought till I started counting up the words. Write until you’ve said what you have to say and then stop. If it’s a short story, fine; if it’s a piece of flash fiction, fine; if it’s a dramatic monologue, fine. There’s an Australian writer, Gerald Murnane, who doesn’t use the terms ‘novel’ or ‘short story’ to describe his writing; he simply talks about ‘works of fiction’ and I get that. Thanks for your comment.

I was blown away by "Fool For Love" when our local professional theater company did it. The writing was intense and honest.

His unusual unmarried relationship with Jessica Lange was intriguing. I don't think they are still together.

There is something rough and sexy about him and his writing.

Great review.

I’ve not seen very many plays, Kass. I’d expected when I moved back to Glasgow that I’d see more but it never worked out that way: four or five Shakespeares, three Becketts a Pinter and a Woody Allen. Now we live in the back of beyond—well back-of-beyond-ish—and so we never go anywhere. It bothers me no end that more plays aren’t shown on TV. I don’t get it. All they have to do is send a live broadcast unit out, set up some mics and maybe a bit of extra lighting and let the actors get on with it. Relatively cheap I would have thought.

Excellent review. Looks like the very thing I'm looking for. Thanks Jim.

Great post, this. I have to say I was enchanted by your extract from The Blinking Eye.

I used to think the short story somewhat inferior to the novel - as do many, I know - but I have been reading them more and more of late - maybe something to do with declining memory and powers of concentration. These seem very much up my alley. Thanks for the review.

Glad to be of help, Jonathan.

And, Dave, yes, I’ve heard people say that but it’s like saying that a string quartet is inferior to a symphony. They are different things requiring different disciplines. I came to the short story late in life. I had already written two and a half novels by then and it was only because I was stuck with the third that I was looking for something else to do since the book was going nowhere. I wrote about forty of them—all based around the ‘other’ senses, sense of humour, sense of righteousness, etc—and I’ve never written one since, just a few pieces of flash. I haven’t sent many out to magazine which is remiss of me but there are only so many hours in the day. About a year ago I did a mass submission but I found that most of the short story mags just never replied which I think is very rude and off-putting. I mean, how long are you supposed to sit on a story before trying it elsewhere? I intend to publish a collection in 2012 entitled Making Sense. My short stories are quite different to both the novels and the poems but I still don’t expect an avalanche of sales. Time to worry about that later. In the meantime I’m expecting the first print run of Milligan and Murphy to arrive any day now—we asked for them for the 6th so Carrie could take a couple with her to the States but here we are, it’s the 9th and still no chap at the door but I still expect to get review copies out for Christmas, later than planned but better late and done right.

Thanks for a beautiful post, Jim.

And also a huge thank you for sharing your writing experiences with me. Its when the faith and trust wavers, that such words from others writers encourage us and give us hope to pursue our dreams.

Thank you, Rachna, I’m glad you enjoyed the post. As for sharing my experiences, they’re limited, but we do what we can. I remember clearly what it was like being an inexperienced writer and I was just desperate to get someone to answer my stupid questions and that’s what I think every time I read a stupid question online: there was a time I would have asked that. Where I do get a bit irked is where people ask questions on boards that they could easily google. One person asked what NaNoWriMo was. Seriously? That’s just wasting other writers’ precious time. Of course people being people—and basically nice—they answered but the simple fact is there is so much information available nowadays for free, at the click of a button.

Post a Comment