Trust in me, just in me

Shut your eyes and trust in me.

You can sleep safe and sound

Knowing I am around.

– Kaa, the python, The Jungle Book

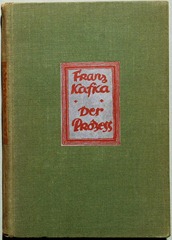

The opening chapters of this book concern an Austrian in Venezuela. As I worked my way through them, two things came to mind: Kafka and Brazil. By Kafka I mean Franz Kafka, not his second cousin Alexander who emigrated to Brazil (which sits next to Venezuela) in 1940, and by Brazil I mean the Kafkaesque film by ex-Python Terry Gilliam. Pythons are very common in both Brazil and Venezuela. They have been known to swallow a human whole. There are no pythons however in The Inheritance but there are snakes in the grass aplenty.

Bear with me. All will become clear. In time.

At Daniel Loew’s bar mitzvah, his uncle, Alexander Stecher Bravo, told him that, in time, he would inherit whatever he had left to pass onto him. Nothing firm is ever discussed – Daniel considers it bad form to talk about such things – but he is not expecting a fortune. There is enough at stake, however, for him to drop everything and travel from London to Caracas to make sure he gets his dues when there turns out to be a problem with the will. His uncle’s intentions sound clear enough:

It is my last will that at the time of my death all my property, all that I own now and shall own in future in Venezuela, whether it be in the form of property, shares or assets of any kind shall be divided as follows: A) All my estate to Mr Daniel Loew, Austrian citizen, currently resident of London

at 16 Agincourt Road. B) Sole exception to this distribution: my Chevy II, 1962, yellow, serial number 469AB62V759. This is to be given to Miss Manuela Ferreira, born 1973. I hereby appoint Mr Julio Kirshman, born on 1st July 1948, to be my executor ...

So his faithful housekeeper gets the car and Daniel gets everything else. That’s what is says, doesn’t it?

Not so fast. What about Alexander Stecher Bravo’s property outside of Venezuela? Who gets that? You see in a letter sent two years before his death his uncle wrote this which clearly shows he hadn't forgotten the promise he made thirty years earlier:

I’m going to leave you my current accounts plus securities held in the German Bank of Latin America in Hamburg, and in their branch in Panama City.

Daniel left things at that and didn’t ask for any more information. For the geographically challenged let me just confirm that neither Hamburg nor Panama City is in Venezuela.

The ‘everything’ that Daniel drops by the way is a pile of poems because that’s what’s Daniel does to earn a crust and, even though he’s a phenomenally successful poet he’s still not living in the lap of luxury and has to depend on his dress designer wife to help him keep the wolves from the door.

“I live modestly,” he says. From time to time he garners literary awards, most recently one called the Hildesheim Rosenstock, a long-established prize, which is awarded by German industry every ten years. “My works have appeared in several languages. Also I translate plays from English into German. Just lately I’ve started teaching seminars in creative writing at an American University in Bristol, which is work that, to me, pays remarkably well.”

That’s more like it. No one makes a living writing poetry. Not these days.

If there’s one question I would like to have asked the author it would be, “Why a poet?” Is it because he wanted a character that had his head in the clouds? If so then there are plenty out there who don’t have their feet planted firmly on the ground without making him a poet. Still, a poet he is and we’re stuck with that.

And the more I read about Daniel Loew the more I realised how naïve, how actually gullible he is. He’s pretty much an innocent when it comes to the ways of the world and he may well have managed to stay that way because he’s always dealt with basically decent people whose word is their bond but this is Caracas; normal rules don’t apply here. That doesn’t mean there are no rules but no one tells you what they are until the game’s afoot and they can change without any notice whatsoever.

You would think it would be a simple thing, have a wee word with the executor who would realise that Daniel’s uncle shouldn’t really have said in Venezuela and, besides, Daniel is the sole beneficiary, discounting the old Chevy, so the money would automatically go him? Yes? No? He phones the executor from London and informs him about the foreign bank accounts. Julio replies:

Don’t worry. We own an eight-storey building here full of merchandise, we really don’t need his money. Now if you’d been lumped with an executor who was hard up, then you wouldn’t have seen a penny! He’d have pocketed the lot, you can bet on that! I just have to pay for the funeral, and his housekeeper and one or two outstanding bills. The rest is yours!

Easy. Nah, not so easy. That when he ends up getting on a plane and heading into a city that was in the throes of a military coup, something Julio forgot to mention. (This would be Hugo Chávez’ failed 1992 military coup.) Daniel could’ve been killed. Now wouldn’t that have been a shame?

That above conversation takes place on pages 35 and 36 of a 228-page novel by the way. On page 177, his lawyer is still optimistic:

“Señor! ... Things are looking very good.”

The lawyer is clearly the kind of man who when he heard the four-minute warning would go, “Heh! We have plenty of time.” Time is a completely different world in South America. No one is in a rush to do anything. Everyone settles into conversations first before thinking about talking about business. Even when his lawyer has some not to good news a few pages later rather than tell him over the phone he arranges for Daniel and his wife, Valeria, to meet with him and his wife on a bus tour of Holland of all things and it is literally hours before he tells him what’s going down. This, by the way, is three years down the line. And we’ve still got 34 pages to go and, as you very well know, a lot can happen in the last 34 pages of a novel.

The thing is, as we start to learn more about Daniel and his relationship with his uncle we start to realise more and more that he is to blame, at least in part, for some of the problems he finds himself now in. In the hotel in Caracas Daniel runs into a woman, a stranger to him, one Esther Moreno, a woman who barges into his life to be more precise, and someone he ends up confiding in. She asks him why he’s there:

“On business?”

“My uncle lived here, for over fifty years ...”

“I see! You’re visiting your uncle! ...”

“He died a few months ago ...”

“And before that ... I mean, while he was alive ... did you never visit him? Or did you have a quarrel?”

“He came to me. Almost every year.”

Well, you see, that last bit’s not exactly true. Later we learn from his uncle (in an imaginary conversation with Daniel):

It’s not true to say that we met every year, not true at all, I only came to Europe every two or three years, we didn’t see each other more than fifteen times in my life. ... I invited you several times to come and visit me in Caracas, my boy, three times we got as far as me wiring you the air-fare, and still you didn’t come, three times you cancelled, each time at the very last minute, bueno, I don’t reproach you, but I still felt hurt, felt like an idiot.

You’ll also have noted that it took a few months before he was fed up waiting on the executor. Which means he never even attended the funeral which is something that the executor points out at the hearing:

We told Herr Loew on the day that Stetcher died that his father’s cousin was no more. Then it was some five months before he came to Caracas. Further, it was I who paid the costs for the funeral, and had the stone put up on the grave, which was something Herr Daniel Loew had promised, as a last honouring of the dead, but failed to do.

What finally goaded Daniel into action was when he decided to contact the German Bank of Latin America directly only to be told, by one Simone von Oelffen (another player in the game), that the executor had come bearing power of attorney and closed the accounts:

“I’ll certainly see what I can do. Will you come and see me this evening. At home. I can speak to you here ... not as freely as I should like. If you see what I mean.” She pushed a piece of paper with her address across to him.

He had the knack of winning people over right away by his shy and yet intense manner. He did it without any particular effort, with his open, smiling expression, and he was courteous, a trait that was especially effective with women.

Yes, there’s no doubt that he has a way with women although he doesn’t have his way with Simone von Oelffen or Esther Moreno but even if he had this is the 21st century and it would just have been sex. This doesn’t mean that Daniel is the doting, faithful husband because we learn that he’s not. Perhaps before this he was and had this never happened very likely he would have remained so but people change and what we witness over these 228 pages is a guy waking up and falling asleep at the same time: he sees what he wants to see and loses interest in everything else.

It’s not who he’s sleeping with that Daniel needs to worry about but who he’s in bed with because in his business dealings all his problems arise from crawling under the covers with the wrong people. Basically it’s pillow talk that seals his fate. He trusts all the wrong people. Beginning with the persuasive Esther Moreno:

Every sentence he speaks, every word she says, every movement of his body, every stirring of hers, adds to the number of threads binding him to the room, and the woman. He is getting tangled up in Esther Moreno’s presence.

[...]

She sits on the edge of the bed, bolt upright, hands folded in her lap. “You ought to confide in me. What have you got to lose? Tell me your story. I’m experienced, I know a bit about life. I can give you good advice. Trust me. It’s not in your nature to try and keep things secret. You want to share, give yourself, open yourself to others, don’t you.”

I read some of the reviews of the German edition and Google Translate didn’t use the word ‘inheritance’ (Erbschaft) it used ‘heritage’ (Erbe) instead which got me thinking about the subtext. Because all the legal toing and froing isn’t especially exciting reading. And besides that’s not really what this book is about. Just as fans of courtroom dramas might find The Trial not to their tastes they should also avoid this one. For the most part all the negotiating, intrigue, backhanders and double-crossing takes place off-page. What is fascinating is watching this Jew’s life crumble around him. At one point during the awful Holland trip his lawyer’s wife asks him:

“Do you wear phylacteries when praying?”

Daniel shook his head.

“Do it, my wife’s right,” Amadeo follows up, “I would even beg of you. Do it – tefillin work wonders, believe me! Start as soon as you can.”

Shortly thereafter Daniel signs the paperwork giving his lawyer “the right to forty-five per cent of the sum at issue, following any successful resolution of the case.”

For those who don’t know Tefillin are two small black boxes with black straps attached to them; Jewish men are required to place one box on their head and tie the other one on their arm each weekday morning. This is due to a literal reading of Deuteronomy 6:5-8 which says “Take to heart these instructions with which I charge you this day. Impress them upon your children. Recite them when you stay at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you get up. Bind them as a sign on your hand and let them serve as a frontlet between your eyes.”

Some days later he is to be found in his attic saying morning prayers in his attic lest his wife make fun of him, Daniel Loew, a descendent of the rabbis Yehuda Mordechai Cassuto and Rav Shmuel Hirsch. Yes, this is as much a book about a man’s heritage as it is about his inheritance.

Some of the book takes place in flashbacks. The first half-a-dozen chapters are a little confusing and I didn’t see what was gained by jumping back and forth but after that they make more sense, pauses to remember and for the reader to catch up. The conversations he has in his head with his dead uncle are also a nice touch, a novel way to prove some exposition without it feeling like a page full of facts. I may borrow that myself.

In his 1999 review, Peter Stuiber says that Daniel is a “modern Michael Kohlhaas.” I hadn’t heard of him before but Wikipedia came to the rescue:

Michael Kohlhaas is an 1811 novella by Heinrich von Kleist, based on a 16th-century story of Hans Kohlhase.

Both the theme (a fanatical quest for justice) and the style (existentialist detachment posing as a chronicle) are surprisingly modern. They resonated with other writers more than a century after they were written. Kafka devoted one of only two public appearances in his whole life to reading passages from Michael Kohlhaas. Kafka said that he "could not even think of [this work] without being moved to tears and enthusiasm."

I have no idea if any of that was known to Jungk before he wrote this book but it wouldn’t surprise me. I don’t think anywhere does Daniel say anything like, “It’s not about the money,” but much as it’s a lot of money (and as things progress he learns of even more mysterious accounts) I still don’t think that’s what drives him on. I might be wrong.

I enjoyed this book. It’s not Kafka (what happens to Daniel is too believable) and it’s not Terry Gilliam (it’s too serious for that although I’d love to see him adapt the book for the screen). The characters are real even the minor ones. The bad guys are not as bad as you think nor are the good guys as good. And don’t talk to anyone about anything without first checking their family tree – you have no idea who they might be related to. The fundamental question that the book asks is not so much whether Daniel has a right to the money but whether he deserves it. And if the man who begins this journey didn’t does the man we leave at the end of the book?

***

Other blogs reviewing this book in the near future:

Wormauld: a Life in Books and Music: 16th June

Winstonsdads Blog: 17th June

A Common Reader: 18th June

4 comments:

After being the micro-manager of my dad's estate after his trustee and advisor lost most of his money on junk bonds, I abhor anything to do with legal and estate issues.

Who is deserving of anyone's life savings? Do we earn inheritance rights by showing or feigning affection?

I like the symbolism implicit in how you've described this book. "...a guy waking up and falling asleep at the same time."....being 'in bed' with the wrong people.

You've done a good job here. I was also very fascinated with Terry Gilliam's Brazil. Some of those images will forever be in my mind. The duct work - the face lift.

Great review.

I’m a bureaucrat at heart, Kass. I like organised systems with clear rules. What I hate is when the bureaucrats use their systems to exert power which they usually do by making the rules overly complicated and the forms long and involved. Carrie and I know exactly what this feels like. At the moment we’re trying to sort out a claim which has already taken a couple of years and will very likely take another year and possibly longer if we have to appeal which I guess they hope we won’t do, just give in and give up. It’s tiresome and unnecessary, totally unnecessary.

I’m glad you liked the review. This was not a book I thought I was going to like at first until I started to see the parallels. I did get quite caught up in it by the end.

i found the theme universal for the book and enjoyed the setting ,your right about Kafka there is a strong influence of the Jung Prag writers Jungk has wrote about werfel ,all the best stu

Thanks, Stu. Kafka creeps into so many things, doesn’t he? What did we ever compare things to before him?

Post a Comment