You cannot live in the present,

At least not in Wales.

from ‘Welsh Landscape’

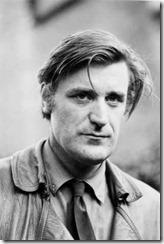

The first poem I ever read by R S Thomas was nearly forty years ago. It was ‘On the Farm’:

On the Farm

There was Dai Puw. He was no good.

They put him in the fields to dock swedes,

And took the knife from him, when he came home

At late evening with a grin

Like the slash of a knife on his face.

There was Llew Puw, and he was no good.

Every evening after the ploughing

With the big tractor he would sit in his chair,

And stare into the tangled fire garden,

Opening his slow lips like a snail.

There was Huw Puw, too. What shall I say?

I have heard him whistling in the hedges

On and on, as though winter

Would never again leave those fields,

And all the trees were deformed.

And lastly there was the girl:

Beauty under some spell of the beast.

Her pale face was the lantern

By which they read in life's dark book

The shrill sentence: God is love.

I have no idea what the teacher had to say about it but I have never been able to shake the uncomfortable feeling I get when I read it. It’s set in Wales but with a slight readjustment, a name change here and there, and it would work just as well in Arkansas or West Virginia. The teacher may not have even told us that Thomas was Welsh because I

I have mixed feelings about needing to know stuff about a writer or an artist or a composer to appreciate their work. Yes, knowing that R S Thomas was Welsh enhances the experience but the simple fact is he’s talking about poor folk, peasants if you want a more romantic term, and there are peasants the world over. I know nothing about Arkansas or West Virginia but I read the poem to my wife and asked her where in America it could be set and those were her first choices.

So I never knew that a priest had written this. That would have certainly affected my reading of the piece. If only to confuse me. If God is love, as the Bible tells me so, then what have the Puws to do with God? In an article in Poetry Wales, John Pikoulis says this:

It is an uncomfortably ironic moment. If God is love, then the Puws are his Forsterian 'ou-boum'.[1]

That quote needs some explaining. In Forster’s A Passage to India there’s a scene where Mrs Moore finds herself in an unusual cave:

The echo in a Marabar cave is entirely devoid of distinction. Whatever is said, the same monotonous noise replies, and quivers up and down the walls until it is absorbed into the roof. 'Boum' is the sound as far as the human alphabet can express it, or 'bououm', or 'ou-boum,' — utterly dull. Hope, politeness, the blowing of a nose, the squeak of a boot, all produce 'boum'. Coming at a moment when [Mrs. Moore] chanced to be fatigued, it had managed to murmur: 'Pathos, piety, courage — they exist, but are identical, and so is filth. Everything exists, nothing has value.' If one had spoken vileness in that place, or quoted lofty poetry, the comment would have been the same — 'ou-boum.'.[2]

I’ve read this over several times but I’m still not sure what Pikoulis is getting at exactly. What proof do the Puws have that God is love? If I’m reading it right then everything

I couldn’t articulate it at the time what struck me about this poem was exactly the same thing that had struck me about ‘Mr. Bleaney’, although if I’m being honest I have no idea which one I heard first. It’s the sense of being led by the poet up to a precipice of understanding and being left. I didn’t understand ‘On the Farm’ when I first read it and I have little doubt that any explanation from the teacher would have been inadequate, superficial at least. This is less a criticism of her and more a criticism of the education system at the time.

So I was left and “[w]hat does a man do with his silence, his aloneness, but suffer the sapping of unanswerable questions?”[5]

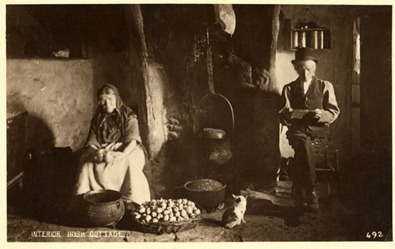

The next time I expect I ran across R S Thomas it would have been in an anthology of 20th century verse. I remember once I’d left school plodding through various collections trying to find poets to connect with. ‘Evans’ was the next poem to strike me:

Evans

Evans? Yes, many a time

I came down his bare flight

Of stairs into the gaunt kitchen

With its wood fire, where crickets sang

Accompaniment to the black kettle’s

Whine, and so into the cold

Dark to smother in the thick tide

Of night that drifted about the walls

Of his stark farm on the hill ridge.

It was not the dark filling my eyes

And mouth appalled me; not even the drip

Of rain like blood from the one tree

Weather-tortured. It was the dark

Silting the veins of that sick man

I left stranded upon the vast

And lonely shore of his bleak bed.

When I first read that I assumed it was a doctor leaving Evans’ house, going down the stairs and out the door into the night. Knowing what I know of Thomas now I can see that it’s more than likely this was a pastoral visit and it’s Thomas himself that’s leaving. His visit has brought the man cold comfort. I never noticed the religious symbolism but I doubt I was looking for it. It was a poem just like ‘Mr. Bleaney’. Bleaney is not the true subject of the poem even though he’s pretty much all the narrator talks about and Evans is not the true subject here, not really; he just happens to be the poor sod lying on his deathbed facing eternity.

The poem is Beckettian. I didn’t make the connection at the time. Had I then I might have made more of an effort to learn more about him. Sadly years went by without me stumbling across more than a handful of poems and it was only after his death that I began reading him. And what do you know, apart from the Puws and Evans there were others, Walter Llywarch, Job Davies and one in particular: Iago Prytherch.

If you’re not Welsh then a name like Iago Prytherch sounds exotic; it’s not. Iago apparently is simply a cognate of James[6]. Welsh surnames are relatively few in number, but they have an inordinately large number of spellings. Prytherch is a variant of Prothero. So it’s a fairly common Welsh name, a suitable name for the common man because Iago is not one particular person. He makes his first appearance in 1942 in one of Thomas’s earliest poems and we’re left in no doubt as to what Iago Prytherch is because he writes “this is your prototype” this “ordinary man” and for twenty years he kept finding his way into Thomas’s poetry.

Thomas was to write more than twenty poems about Iago Prytherch, a character who can easily be (and has often been) seen simultaneously, as his protagonist and antagonist, his personal persona, even as a kind of alter ego.[7]

I am Prytherch. Forgive me. I don't know

What you are talking about; your thoughts flow

Too swiftly for me; I cannot dawdle

Along their banks and fish in their quick stream

With crude fingers. I am alone, exposed

In my own fields with no place to run

From your sharp eyes. I

from ‘Invasion on the Farm’

Like most things he cared about Thomas is often ambivalent when it comes to Iago. At times we have him presented as a dimwit:

Motionless, except when he leans to gob in the fire,

There is something frightening in the vacancy of his mind

from ‘A Peasant’

and yet when you start to compare all the ‘Iago Prytherch’ poems what one is forced to realise is that this is less of an extended character study that a continual reassessing of his common man persona. By 1961 we have a very different picture of the man:

Which?

And Prytherch – was he a real man,

Rolling his pain day after day

Up life's hill? Was he a survival

Of a lost past, wearing the times'

Shabbier casts-off, refusing to change

His lean horse for the quick tractor?

Or was a wish to have him so

Responsible for his frayed shape?

Could I have said he was a scholar

Of the fields’ pages he turned more slowly

Season by season, or nature’s fool,

Born to blur with his moist eye

The clear passages of a book

You came to finger with deft touch?

From a brainless peasant he’s suddenly become a Welsh Sisyphus rejecting progress, rejecting the present in favour of a better past. Thomas’s view of the common man did change over the years. In 1955 he published what basically amounts to an apology:

Prytherch, man, can you forgive

From your stone altar on which the light’s

Bread is broken at dusk and dawn

One who strafed you with thin scorn

From the cheap gallery of his mind?

from ‘Absolution’

Thomas had arrived in Manafon an intellectual, a bit of a snob. His son maintains that he continued as one throughout his life, nevertheless, as he continued his journey westward (stopping only when he reached the sea) he did mellow somewhat and maybe that’s what we see in the poetry. Who says a man can’t change his mind?

But look at yourself

Now, a servant hired to flog

The life out of the slow soil,

Or come obediently as a dog

To the pound’s whistle. Can’t you see

Behind the smile on the times’ face

The cold brain of the machine

That will destroy you and your race.

from ‘Too Late’

Twenty-five years later in this simple poem it’s clear that Thomas believes we have seen the last of Wales’s Iagos:

Fuel

And the machines say, laughing

up what would have been sleeves

in the old days: ‘We are at

your service.’ ‘Take us’, we cry,

‘to the places that are far off

from yourselves.’ And so they do

at a price that is the alloy in

the thought that we cannot do without them.

I can understand why Thomas may not be as popular as his countryman of the same name, Dylan Thomas – everyone loves a rogue – but, for me, he’s the finer poet, not that Dylan Thomas is a bad poet; far from it.

Although Thomas’s poetry is rooted in Wales it has a universal appeal because the issues he talks about are ones people can relate to the world over. Iago Prytherch may be Thomas’s everyman but he has a literary predecessor: Paddy McGuire, in Patrick Kavanagh’s ‘The Great Hunger’:

Clay is the word and clay is the flesh

Where the potato-gatherers like mechanised scarecrows move

Along the side-fall of the hill - Maguire and his men.

If we watch them an hour is there anything we can prove

Of life as it is broken-backed over the Book

Of Death?

from ‘The Great Hunger’

During his lifetime, Kavanagh earned the reputation of a “peasant poet,” an epithet he disliked because it failed to acknowledge the originality and quality of his verse, but rather focused on his being a self-taught poet from rural

Progress

is not with the machine;

it is a turning aside,

a bending over a still pool.

From ‘Aside’

“Without the peasant base civilisation must die,”[10] wrote Kavanagh, “only one remove from the beasts he drives.” Thomas wrote something similar: “moving through the fields ... with a beast’s gait”[11] and

The day I saw you loitering with the cows,

Yourself one of them but for the smile

from ‘Valediction’

All of which makes me feel in many ways Thomas was a bit naïve. You can’t turn your back on progress and hope it will go away. I’m also not entirely convinced that Wales was as important to him as people might imagine. He was concerned with bigger issues. The English intrusion was symbolic of the modern world’s intrusion into the pastoral. It was a convenient cause. This does not mean he wasn’t passionate because he clearly was. In fact he’s infamous as being the pacifist who appeared to condone the fire-bombing of English holiday homes by the Sons of Glyndŵr ("Even if one Englishman got killed, what is that compared to the killing of our nation?"). Statements like that obviously muddy the waters.

He embraced Welshness as a buttress against modernity. It was a means to a greater end. It was not the natural response of a native to a threat to his or her cultural habitat, but rather the more complex response of a cultured individual seeking a barrier to perceived barbarism. The central text for this anti-modern attitude in his work is his lecture Abercuawg, his most extended transcendental vision, where he expresses doubt as to whether a modern world would be worth sacrificing for.[12]

Thomas writes hard, uncharitable poems. He also writes direct, accessible poetry. Yes, there are layers and a religious upbringing may help you with the subtext but even a superficial reading of his poetry can be inspiring. Certainly if you want to learn how to write poetry he should be on your list of poets to study. Before anything else he was a poet. You can see that here in the opening to this poem:

I often call there.

There are no poems in it

for me. But as a gesture

of independence of the speeding

traffic I am a part

of.

from ‘Llananno’

Gift

Some ask the world

and are diminished

in the receiving

of it. You gave me

only this small pool

that the more I drink

from, the more overflows

me with sourceless light.

P.S. After posting my last article on Thomas, Davide Trame (who most of you will know from his comments on various sites as Tommaso Gervasutti because that's the name of his blog) contacted me to express his appreciation for the article since R S Thomas is probbaly his favourite poet. He included the following poem which I thought I'd share here:

R.S.THOMAS

In the relentless words at target

of a mind accurately kneeling,

acutely staring at the infinity of a face

advancing and receding,

you can see me too in my darkness,

in my pulsing silence. I jump for joy

because you have bared

the gnawed bone of my being

that is shining now thin and true,

the shout of a nerve in tune

with the grinding jewel

of your persistence.

FURTHER READING

A selection of poems online: poetryconnection.net

REFERENCES

[1] John Pikoulis, Martin Roberts, ‘R.S. Thomas's Existential Agony’, Poetry Wales, Vol. 29, No 1 (July 1993)

[2] E M Forster, A Passage to India, p.5

[3] Patrick Kavanagh, ‘The Great Hunger’

[4] Then a voice came from heaven, "I have glorified it, and will glorify it again." The crowd that was there and heard it said it had thundered; others said an angel had spoken to him. – John 12:28-29 (New International Version)

[5] R.S. Thomas' Collected Later Poems 1988-2000, p.21

[6] The Oxford Dictionary of Surnames gives 'Iago' as Welsh form of 'Jack', either (1) from Fr. Jacques < Lat. Jacobus or (2) from "a pet form of John, fr Low German and Dutch Jankin < Jan + the dim.sufix -in (The loss of the nasal was a regular development in Low Ger.)

[7] William Virgil Davis, R.S. Thomas: Poetry and Theology, p.25

[8] R S Thomas, 'Abercuawg', R.S.Thomas Selected Prose, edited by Sandra Anstey, p.126

[9] M Wynn Thomas, ‘R S Thomas: War Poet’, Welsh Writing in English: A Yearbook of Critical Essays, Volume 2 (1996): 82-97

[10] Patrick Kavanagh, ‘The Great Hunger’

[11] ‘The Last of the Peasantry’, Collected Poems: 1945-1990, p.66

[12] Grahame Davies, ‘Resident Aliens: R. S. Thomas and the Anti-Modern Movement’,

Welsh Writing in English: A Yearbook of Critical Essays 7 (2001-02): p.50-77

19 comments:

Like Davide, I admire and appreciate R S Thomas. He had considerable talent. I am also envious of his snobbery. I think life is easier when you know you have observational and intellectual powers and can hold yourself separate from most other humans. It seems it would be easier to have this stance than to grovel, beg and badger people into understanding your offerings.

An excellent continuation of R S Thomas poems, background and critisism! (an excellent poem by Davide, too)

excellent biography of R.S. Thomas by Byron Rogers titled "The Man Who Went Into The West"....

I’m not sure I could find it within me to be envious of any snob, Kass, and I regret using my intellect such as it is to distance myself from people. I remember one chap approaching my last wife saying he’d like to be friends with me but didn’t know how to approach me. I find that sad. How many never made the effort? How many friends might I have had if I hadn’t thought myself better than them? I’ve always been different to the people around me. I’ve never had the company of fellow writers and so I’ve always been different to my peers. Different is not better than though. I think the superiority was a coping mechanism to be honest but one I developed long before I became a writer. School kids can be cruel and I was picked on in Primary School. I wasn’t alone but I felt alone. I coped by a fluke of attitude. Rather than feeling less than them I chose to believe I was better than them. It’s a coping mechanism you will have been familiar with as a Mormon; there’s you and there are the non-believers and even though you are in the minority you can’t help but feel superior only you would call it ‘blessed’ or ‘chosen’ which are just ways of saying ‘we know something you don’t know so nah nah!’

And, Bill, yes, references to that book cropped up throughout my research. Didn’t have time to read it but it sounds like a fascinating read. I really feel I’ve only scratched the surface here.

I appreciate reading more on Thomas. I think your overview is probably pretty accurate.

I'm waiting for the comparison to Robinson Jeffers, because there IS common ground there, both in subject matter and in the bleak view of human nature. Having made myself into an amateur Jeffers scholar in recent years, I for one feel some commonalities to be present.

As for the echo in the Marabar Caves, it's central to the entire novel. The echo is the central image that makes every action that follows in the novel equivocal and uncertain and to be questioned. No one really knows what happened in the Caves, and we're never told with any certainty; it's the central mystery of the novel, the pivot on which everything turns. The echo is the uncertainty about what happened in the Caves; was Adela attacked or wasn't she? something distressful did occur, but what was it? We never know, not even at novel's end.

The echo in the Caves is what sends Mrs. Moore into spiritual shock, so dominating her mind afterwards that she doesn't care anymore about life and death or anything. It's all lost in the echo. The echo removes all meaning from her life. Even "God is love" comes back as "ou-boum."

I've had my own experience of the echo, and not just in India. For me it's symbolically tied to the dark night of the soul, to the Void, and so forth. I wrote a poem about the echo, and then later made it into a piece of text-sound poetry:

because the echo

I enjoy reading more on R S Thomas, Jim. He comes across as richly textured for me in this second review. I find I like him more despite his snobbishness.

I'm also intrigued by what you say here about adopting a superior attitude as a way of defending yourself against the bullies.

I think this happens more than we realise. Bully and victims can become polar opposites and sometimes they simply switch places.

Not that you'd ever be a bully, Jim. I simply can't see that given your sensitivity and kindness on line.

Thanks, Jim. I also love Davide's poem. I admire the fact that one person can become so enamored of another poet is inspired to write a sort of dedication to the poet. And what a dedication, what a poem. Thanks.

A bully isn’t necessarily a bad person, Lis, although your classic Flashman-type most definitely is. A bully is someone who needs to get their own way and will manipulate people in order to do that. Looking back on my past I can see hundreds of times where, by the use of passive aggression, I’ve got people to see, or do, things my way. I never thought of myself as a bad, or even a selfish person, but the fact is that I was nowhere near the kind of person I thought I was. In my head I only wanted what was best for all and my way was always the best way. Of course often it was which bolstered my confidence on the occasions where it wasn’t or, and this was more often the case, it didn’t matter a jot.

I’ve changed quite a lot and shaken off the arrogance of youth but old habits die hard and one thing my psychotherapist pointed out was how passive aggressive I could be. In a situation like that you don’t have time for much of a considered response and I was trying to be ‘myself’ so I guess that side of me is there. She had difficulty keeping control and I would wrest it from her. She even once, and I suspect this was quite unprofessional, admitted that I intimidated her which upset me but I think we were both rather glad when the sessions ended. I don’t enjoy intellectual wrangling the way I used to but it’s obvious when backed into a corner I’ll go down fighting.

This doesn’t mean that the person you see online is a complete fabrication but he is a front which is a form of lie. The only way I know how to change is to live the lie until it becomes the truth. Clearly I have a way to go. My dad was a bully. He never raised his hand to my mother in the fifty-odd years they were married but he totally subjugated her. In my poem ‘Father Figure’ I include the line "In this house I am God." Those are words my father uttered and believed; he could cite scripture to back up his claim. Fine, but what happened to “God is love”, that’s what I want to know? Like me though had you accused him of being unloving he would have been indignant, righteously so, but I imagine there will be many out there who think God is a bully too.

Please feel free to write something about Jeffers, Art. I would have to do a lot of research and I simply don’t have the time at the moment. I, of course, have nothing but time but it vanishes quickly. Carrie has been in America for a week now and yet it feels like she has just left and I’ve done so little. I had imagined without her around to distract me I’d tear through the work but I can only get so much done in a day.

I read the Marabar Caves section of the novel – I found a copy online – but I wasn’t going to read the whole book just to make use of the quote. At least it made sense to you. I get the idea but I’m still not too clear how it was being applied to the Thomas poem and I’m happy to admit that.

I tried to listen to your echo piece – I like the effect – but it’s morning and I have a screaming cockatiel telling the world and his reflections it’s time to wake up and he’ll be at that till lunchtime; his reflections are very lazy. At the moment I’m trying to bury him in Beethoven. He’s rising to the challenge.

I've had to have a couple of bites at that one, Jim. I think you've excelled yourself with it. I think I understand The Farm perfectly - though that may be only in my terms. When i was in Junior school (8,9,10 - can't remember which) we were taken to see a dance display by pupils at a nearby training centre. Today we would call them Special Needs people, back then they were labelled ineducable. At one point there were two rows of pupils facing each other, advancing and retreating. One lad couldn't stop himself going back wards, it seemed. He ended up sprawling in a rose bed. Most of my companions thought it hilarious. The thought that I had was that if life had never managed to advance beyond that, it would still be wonderful. Condescending and missing the point (his point and Einstein's being almost inseparably close), as I know now, but perhaps a glimmer of what Thomas was getting at. At least, that's how it seems to me.

Prytherch is a fantastic figure. Shakespearian in depths and complexities.

All-in-all, a great post.

I don't think of bullies as bad necessarily either, Jim.

Most often I think of bullies as desperate and vulnerable. You'd have to feel vulnerable and unsafe to feel the need to bully other people into doing things your way, or getting them to give you what you think you want or whatever else it is that bullies are motivated by.

Bullies are often victims, too.

Like your dad, my dad was a bully. It seems to me in retrospect he knew no other way. There were times when he could be kind, but the war and his early childhood trauma ruined what decency existed in the man beyond his intellect and his ambition.

I think war has a great deal to answer for and so many of us have been touched by it in one way or another, war and poverty and premature separation from our mothers,sometimes through illness, or through depression, or the birth of a sibling. The list goes on.

Philip Larkin's verse comes to mind:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

Thanks, Jim.

I'm unlikely to be able to write anything comparing Thomas and Jeffers anytime soon, or at least in any depth. I do put it out there for people to pursue on their own time. If I get a chance I will look into writing something or other about it, but at the moment it wouldn't be much and I wouldn't be able to give it much time. I'll just put it on the stove for later.

I agree with you totally about snobbery, Jim. Maybe I should have said I wish I had the confidence that snobs seem to exude. I would never act like a snob, but it would be good to know to the bones that I have value.

These two posts have been a great introduction to Thomas for me, thankyou!

I'm gobsmacked that your dad actually said that.

Excellent, Jim. A fine set of perspectives on my favourite poet. I'd just echo Bill Sherman's recommendation of Byron Rogers recent biography, 'The Man Who Went Into The West, The Life of R. S. Thomas', published by Aurum Press. It's superb.

Yes, there was quite a bit in these posts, Dave, but enough to encourage readers to investigate further at their leisure. What I personally get from On the Farm doesn’t translate well into words but I cherish poems that have its quality like the Larkin poem, Mr Bleaney I’m always going on about. People must wonder why I harp on about it so much and yet never really explain what about it works. The reason is that it’s a feeling. I know I go on a lot about the meaning within poems (and I’m not going back and saying that meaning is not important) but I’m not sure that meaning means anything without feeling. Does that make sense to you? The above two power gave me a shudder of truth, that’s as good an expression as I can come up with but it feels right like the feeling you get when you know you’re being followed – it’s both a sensation and an intellectual awareness.

I’m not sure I would blame the war, Lis for the way my father was. He was in the navy and essentially a mechanic which is what he did his whole life, fiddled with machines the bigger the better. I suspect it was his childhood. He was the youngest of about a dozen kids and had a different father and when they weren’t living in poverty they were certainly next door to it. I know he was the school bully, that he admitted, but as far as we were concerned he was simply the head of his household and sometimes he needed to put his foot down. It’s sounds worse than what it was when he said that he was God in his household, Marion, because I remember him explaining why and in what way he was God (something to do with Moses ... it was a long time ago) but much of it was bluster and frustration with us. The trouble is, when you’ve played a card like that, where do you do from there? The thing was no matter what his family did to embarrass, disappoint of even disgrace him (and all three of us managed to do that in our own ways) he always stood by us. I never felt I couldn’t turn to my dad in times of trouble. So don’t think too harshly of him.

Art, you write what you have time to write, son. If you get inspired then fine. No pressure. I’m not going anywhere.

What I read in your statement about knowing you have value, Kass, is that you feel that determination is for others to make. Others will value you to a greater or lesser extent but the most important thing is your personal worth. You decide on that and you alone. You don’t need others to validate you. Let’s say that all the people who truly love and cherish you are on a plane and that plane crashes and you lose the lot of them – preposterous I know, but bear with me – does that mean you’re value has suddenly crashed? That would be daft. You will be exactly the same person you were before the crash, although probably quite a bit sadder.

And, Dick, I think I’ve commented before on your own poetry how I’ve seen the influence of Thomas there so no great surprise to hear that he’s a favourite.

Jim - Thanks for the reminder of where value resides. This is where any kind of writing is too many steps from reality. I think if you could have seen the expression on my face when I uttered, "I am also envious of his snobbery, " you would have understood the slight sarcasm with a hint of 'let's try this on and see how it feels to say it' that I intended.

Yes Jim, it makes perfect sense to me. The shudder, I think, puts it very well. I agree that emotion must be part of the meaning, and if you could explain a poem what would have been the point of writing it in the first place? It seems clear to me that intellect plays a part in feeling, it differentiates the emotions if nothing else. The (simplistic) example I like to give is that if a small man hits me what I feel is anger, but if a big man hits me the feeling is one of fear. My intellect has detected an element of danger in the second example that was not there in the first.

Yes, Dave, because in many respects the poem is the explanation. By that I mean that, assuming you’ve done your job right, the best words have been used to express the whole thought-emotion experience. Everything can be explained further. A recipe can be broken down into basic chemicals, atoms and molecules but after a while it’s no longer recognisable as what it is. A recipe is sufficient explanation. No one needs to count the grains in a ‘pinch of salt’.

Another wonderful piece to read! Well done, Jim.

I think the Puw's are what RST called "God's failed experiments". Who can girl go with? Someone from the next valley?

You know, Gwilym, I'd never considered that the girl might go anywhere. I imagined her stuck with her odd brothers until the last one bit the dust and only then would she be free.

Post a Comment