I took a speed-reading course and read War and Peace in twenty minutes. It involves Russia - Woody Allen

I open with the Woody Allen gag because it reminds me of when I was a kid, maybe about ten. Having learned that, according to many, War and Peace was regarded as the greatest novel ever written, I ordered the book at my local library. It was a popular tome and so when it arrived I was only permitted to borrow it for two weeks. I made a valiant attempt to get through it but after the fortnight when I tried to renew it I was told other people were waiting and had to hand it back in. I never attempted to read it again.

All I can remember about it is that it was about Russia . . . oh, and the names were all terribly, terribly long. Since then I’ve made my way through a number of Russian novels, all of which had two things in common, they were about Russia and all the characters had terribly long names. And variants on those names depending on the circumstances, which can be confusing. So, before I start talking about The Last Station a brief breakdown on Russian names.

| Every Russian name consists of three parts: a first (given) name, a patronymic name and a surname. Let me illustrate: ● Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev The first name is given by parents shortly after the child's birth. Accordingly to Russian laws child can change the name after majority. The first name is the main name of Russian people. Most of Russian names have a variety of forms: ● The full form Mikhail Sergeyevich is used in formal relationships ● The short name Misha is used by friends and family members. ● The affectionate form Mishenka or Mishunya is used by parents or grandparents. ● The rude form Mishka is an uncouth derivative of the name. |

Each chapter in the book is written as if in the first person by five different people:

● Countess Sophia Andreyevna (Sofya) – wife of 48 years

● Vladmir Grigorevich Chertkov – closest friend, confidant and promoter of his work

● Valentin Fedorovich Bulgakov (Valya) – secretary

● Alexandra Lvovna (Sasha) – youngest daughter who acted as a typist and secretary

● Dr Dushan Petrovich Makovitsky – personal in-house physician

These, along with Tolstoy, are the main protagonists. Mention should be made of three secondary characters:

● Masha, a tall girl, Finnish in appearance who has recently joined the Tolstoyans at Telyatinki (Chertkov’s home). Not to be confused with Tolstoy’s daughter, Masha. She and Bulgakov become romantically involved.

● Varvara Mikhailovna, Sasha’s intimate friend who also does secretarial work at Yasnaya Polyana (the Tolstoy estate).

● Sergeyenko (Chertkov’s secretary)

In addition to the five narrators already mentioned there are also chapters headed L.N. and J.P., the former being excerpts from Tolstoy’s letters, diaries and other writings and the latter being three poems by the author which personally I found out of place but they don’t take up a lot of room.

I was curious why Parini had chosen this approach to his novel. In the book’s afterword he explains that it was because most of the people who were there had either written diaries or produced memoirs after the fact and so he found himself with a fractured picture of what went on; everyone has their own perspective and only by presenting several do we get a rounded picture of the events covered in the book. Why write a novel and not a biography?

Straight biography is fairly rigid in its conventions, and the straight biographer never enters into the subjective consciousness of a subject in the way novelists always do. – Paul Holler, An interview with Jay Parini, Bookslut, April 2006

The marriage of Leo and Sofya was marked from the outset by a mix of sexual passion and emotional insensitivity when Tolstoy, on the eve of their marriage, handed her his diaries detailing his extensive sexual past and the fact that one of the serfs on his estate had borne him a son. From the outset the newlyweds have a tempestuous relationship, full of loving – and angry –

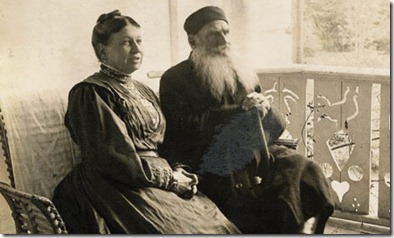

When the book opens Tolstoy is eighty-two and his wife about to turn sixty-six. It’s clear from the off that their relationship is a complex one. Everyone bar family refers to Tolstoy as Leo Nikolayevich, however his wife calls him by the affectionate name Lyovochka. In the first chapter Sofya Andreyevna is doing the talking. Her husband is asleep:

Lyovochka slept on, snoring, as I smoothed his hair. The white hair tumbles on his starchy pillow. The white beard like spindrift, a soft spray of hair, not coarse like my father’s. I spoke to him as he slept, called him ‘my little darling.’ He is like a child in his old age, all mine to coddle, to care for, to protect from the insane people who descend upon us daily, his so-called disciples – all led on, inspired, by Chertkov, who is positively satanic. They think he is Christ. Lyovochka thinks he is Christ.

So Sofya sees herself as the faithful and loving wife-cum-protector of her aged, slightly dotty husband.

I don’t want to prejudice you against Sofya Andreyevna, but it would be impolite of me not to mention her disagreements with Leo Nikolayevich. It has been an unfortunate marriage – for him. Frankly she is not one of us. I would go so far as to say that she despises us and would do anything in her power to see that her husband’s work does not go forward.

So, as you can see there’s no love lost between the two. And it only gets worse as the book progresses.

By the time he is well into his fifties, Tolstoy was constantly in touch with learned men and philosophers (there are

What can we say about Sofya other than this is not what she signed up for. She married a count; she is now a countess and expects to live and be treated like one. It is a mark of Tolstoy’s love and regard for her that he allows her to continue in the manner to which she has become accustomed. He continues to live in the lap of luxury although this is against all his principles and clearly pains him.

Many have wondered why he did not turn his back on the family and his rich estate, as he clearly desired to do, and go off to live in a hut as an impoverished religious hermit. This would have squared him with his conscience which on this score never gave him any peace of mind. But more than once he explained, and there is no good reason to doubt his sincerity, that this way out was a temptation which he must resist, for he was convinced that he had to work out his salvation in the milieu where God had placed him. - Ernest Joseph Simmons, Tolstoy, p.130

The main subject of conflict in the book concerns Tolstoy’s will. Sofya writes:

There is something going on behind my back, something to do with the will. Yesterday, I asked Lyovochka directly, ‘Has anyone approached you about your will? Has anything changed? You would tell me, wouldn’t you, if anything happened?’

He thinks he can give away everything we own: the house, the land, the copyright to all his works. Has he no sense of responsibility?

‘You mustn’t worry, Sofya,’ he said. ‘Nothing has happened.’ But I’m worried.

Of course she has every right to be worried. But Sofya being who she is isn’t content to be worried. She spies on her husband, is often at loggerheads with him in public, runs around with a loaded gun and even attempts suicide in a bid to gain the upper hand. Tolstoy bends over backwards to keep the peace. Her most vicious attacks are understandably against his relationship with Chertkov:

It’s unnatural for a man of my husband’s age to cluck and coo over a beastly younger disciple.

She demands to read her husband’s diaries for evidence of impropriety:

‘I want to read all your diaries from the last ten years.’

‘I’m afraid that’s impossible.’ He looked away from me as I spoke.

‘Where are they Lyovochka? Where have you hidden them?

‘I have not hidden them.’

‘Are they here?’

‘No.’

‘Does Chertkov have them?’

‘Please, Sofya. I . . . I –‘

‘I knew it! He is greedily reading everything you have said about me. This is despicable. Have I not been an honest, loving wife for all these years? Answer me, Lyovochka!’

‘“Beauty has always been a huge factor in my attraction to people. . . . There is Dyakov, for instance. How could I ever forget the night we left Pirogovo together, when, wrapped in my blanket, I felt as though I could devour him with kisses and weep for joy. Lust was not absent, yet it is impossible to say exactly what part it played in my feelings, for my mind never tempted me with depraved images.”’

Leo Nikolayevich, looking disgusted, stood and excused himself. I was relieved.

‘See what you’ve done, Sofya Andreyevna? He has been driven from his own terrace,’ said Dr Makovitsky.

‘He is aware that I have hit upon the truth. Why else would he chase about like a schoolboy after Vladimir Grigorevich? He lusts after the man. He wants to roll about in bed with him, to smother him with kisses, to weep on his breast. Why doesn’t he admit it? Why doesn’t he just do it?

Parini doesn’t explore or explain these entries in Tolstoy’s diaries any more that he pursues the lesbian inclinations of Tolstoy’s daughter Sasha. Tolstoy asks his daughter pointedly at one point if she loves Varvara and is happy to hear that she does. Whether they have consummated that love is never pursued. The feeling I got from the book is that both loves, Sasha’s for Varvara and Tolstoy’s for Chertkov, are fairly innocent. Sasha writes:

He’s always buoyant when he has seen or is about to see Chertkov. He loves Vladimir Grigorevich as I love Varvara Mikhailovna. I would never begrudge him this.

Anything else really has to be conjecture. But this is also where Parini’s approach works well because here we have Chertkov’s point of view:

People are mistaken when they say I love the man. What I love is the Tolstoyan firmness, the call to truth and justice. The lineaments of his prose entangle, embody, render visible the elusive matters of these virtues.

Descriptions of the physical attraction between men appear in The Cossacks and Anna Karenina and other works. Tolstoy also describes homosexual attractions in his autobiographical Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth. By the time Tolstoy wrote his last novel, Resurrection, he had turned against all sexuality, and he considered homosexuality as simply one more symptom of the moral decay of society. He even had doubts about the role of sex within marriage. Certainly he and Sofya had not been intimate in some time.

The Tolstoyans’ view was not, however, that all sex was wrong but sex outside marriage was certainly frowned

The situation between Tolstoy and his wife proves untenable. Short breaks don’t work, writing her letters doesn’t work, and pleading with her face-to-face doesn’t work. Finally, on discovering that she’d been searching through his office looking for a new will, he decides to flee and in the early hours one morning leaves with a small band. Tolstoy, Bulgakov, Sasha and the good doctor head off with the bare essentials:

‘I can take nothing that isn’t absolutely necessary.’ These included a flashlight, a fur coat, and the apparatus for taking an enema.

The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy have recently been published by Alma Books and I was offered a copy for review but it never arrived in the post. Having read this book I’m rather glad; I can see that her diaries would present a very one-sided view of the goings on at Yasnaya Polyana, the 4,000-acre estate where she lived for more than half a century. Also apparently the events of the last ten days of her husband’s life are barely touched on by her in her diaries; no doubt she was too distraught to write. That her diaries of Sophia Tolstoy were not published in Russia in the 1970s is clearly indicative of their content. They do not present the great man in a good light.

I’ve seen The Last Station criticised because it focuses on Sofya. I really can’t see how it could do otherwise. She’s by far the most interesting character. It’s she that turns this from an engrossing piece of academia into a real page-turner. I’ve not seen Helen Mirren’s performance other than a few clips but from what I’ve read her Oscar nomination was no surprise. That said The Telegraph calls the film “a stuffy non-starter of a prestige picture with more putative class than intelligence.” So who knows? It’s certainly has the potential of being the role of a lifetime because Sofya’s mood swings are extreme, the whole gamut from empress to madwoman. A number of other reviewers have noted that The Last Station is a film script masquerading as a novel and I can’t disagree.

My main problem with it, as you’ll see from this review, is that you really need to know quite a bit to put the storyline in its proper context. Parini does as good a job as any in balancing back-story and action but there were things I would have preferred to know more about, for example, I would have liked to learned how the “Nihilist [a man] completely without faith” (which is how he describes himself in What I Believe) became the Christ-like figure we read about in this book; everyone, even illiterate peasants, revered him. And also how did this most revered of men manage to get himself excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church? That said, as an overview to a serious study of Tolstoy I think it does a good job.

Some may object to the way he has “Englished” (his word) quotations by Tolstoy. His reasoning was to make sure the Tolstoy of history and “the Tolstoy of his invention” sounded like the same man. I didn’t find it a problem. I didn’t even notice it. What he does do on occasion is modernise the dialogue. Purists will most certainly grue when Sofya says things like “I don’t find it amusing. I find it sick,” but it didn’t upset me. Then I don’t know any better.

Unlike many historical novels Parini has had the benefit of a great deal of data recorded at the time and shortly thereafter by people directly involved in his story. How accurately he has interpreted that data is anyone’s guess. Historical accuracy aside what I can say is that this is a well-written, very readable novel – in his afterword he is keen to emphasise that it “is fiction, though it bears some of the trappings and effects of literary scholarship” – and, bearing in mind we all know how the book is going to end (and if we didn’t the blurb on the back of the book tells us), he also manages to build up a reasonable amount of tension and anticipation in the final few pages.

***

10 comments:

I don't usually read long novels, but did enjoy Anna Karenina, apart from some of the long-winded descriptions of agricultural life in Russia.

What can I say, Joe, other than this is definitely not as long as Anna Karenina. It’s probably not as good if Anna Karenina’s all it’s cracked up to be. But for what it is it does a decent job in very much the same way as Warwick Collins’ book The Sonnets is a light introduction to Shakespeare’s sonnets. From there you break out the real textbooks.

Jim - First, I just have to tell you how much I like it when you say someone is "dotty." This must be a British or Scotch phrase. It's not used so much on this side of the pond, but I love it. "Clear from the off," is pretty good too.

I enjoyed this review. I've read a bit of Tolstoy and have been fascinated by his moral writings. I hope he appreciated being excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church. It would be interesting to see what, if anything, he wrote about that event.

Were you confused by Parini's lack of explanation as to the reasons, or is there an unclear justification in your mind? Google stuff says he was a Christian anarchist and someone without any belief in immortality. He saw Christ as simply a man and made it clear that he rejected the authority of the church. After he wrote The Kreutzer Sonata , where the main character strangles and stabs to death his wife because he believes she is having an affair, he was accused of preaching immorality. The Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod wrote to the tsar, and this was the beginning of the process that led ultimately to his excommunication. His novel Resurrection also had strong criticism of church ritual. (I left quotes out because I jumbled the Google information into a mess).

I wonder how you react to Tolstoy's statement, "The one thing that is necessary, in life as in art, is to tell the truth."

I do agree that Sofya seems most interesting and I like the idea of their angry passion. I'm with her, though, in being upset by the detailed descriptions of dalliances on the eve of a wedding. Sounds like pretty clumsy foreplay.

Good review. It makes me want to read more Tolstoy (his moral stuff).

BTW, I appreciate your comment on my poetic attempts. I agree that 'loopy' is not the best way to describe legs intertwining. Would it be better to say 'looped?' As I reread my daily April outpourings, I'm vexed at how much they remind me of what I wrote in High School. I was enticed by ReadWritePoetry's challenge, even though I would never venture to submit anything. I have new-found respect for all accomplished poets now (including you). IT'S HARD!

I don't want to read it. There. I've said it. I feel compelled to apologise now but that would make my opinion seem trite and not thought out, which it isn't and is, but my reasons are too long winded and ill worded - real Russian names of thoughts - to place legibly.

I thank you for review though and for saving me some life.

I’m glad my idiosyncratic speech patterns amuse you, Kass. I pretty much write as I speak. I like to add a bit of colour especially when describing something that could otherwise be a bit dry.

I’m fairly clear what Tolstoy’s beliefs were and the reason for his excommunication. Parini's book is a novel and so skirts over so much material. If anything that’s my main objection to it, the fact that to appreciate the finer detail I had to do my own research. But I see this all the time in historical work. You have to trim the fat, decide what your book/film is really about and focus on that, providing a simplified version of the truth rather than try and fit everything in an overwhelm your reader.

As for Tolstoy’s statement I agree that we should all aspire to the truth but we should be realistic when it comes to our abilities. Truths are not cold facts and the simple – okay, not very simple – truth is that everything I do is a consequence of everything I have done before. We’re constantly course correcting, a degree here, a degree there. Truth is also an assemblage, something we construct over years. The best we can end up with is something that resembles the truth in just the same way a photograph resembles the sitter, an aspect of the sitter at least, at that point in time. In that respect truth is like memory. There are old truths in fact probably the only way to identify any truth is after the fact which is why the sculptor or the painter steps back from his work from time to time because when he is involved in it he is too close to the truth to see it for what it is.

As for you poem, you’ll have to decide. My gut feeling is that if you need other people to tell you that ‘looped’ is okay then it probably isn’t. I simply told you how ‘loopy’ affected me. You can’t please all of the people all of the time. The problem here is that you’re describing something that’s been written about so many times before, ‘entwine’ being the verb of choice in the past, but ‘entwine’ is veering towards cliché now so you really have to think of something fresh.

And, Rachel, that’s the whole purpose of reviews, to save you time. There are so many books that I’ve avoided based on reviews. But it’s also reviews that help me make up my mind to buy others. Had I not been sent this book I wouldn’t have bought it. That’s not what you say in a review because it suggests there’s something wrong about it. There isn’t. It’s just not what I prefer to spend my spare pennies on. I remember when I was about nineteen being in Smiths in Glasgow and spending three hours there and buying nothing because I couldn’t choose. I was terrified I would waste my money which is one of the main reasons I rarely buy full-priced books anymore. But then when I was rich I never thought twice about it.

Jim, I'm much the same when it comes to allocating my dosh but I don't feel bad about deciding not to read something. Gone are the days when, like Austen, one could literally read every book being published. I don't have enough lifespan to read the books I want to read, without trying to cram in ones which don't appeal.

But I did enjoy your review.

I have to say, for me it's Pasternak. I've read Doestoevsky, Chekov, some Tolstoy stories, some Solzhenitsyn (the shorter works; his book of prose-poems is quite good), and bits of other Russian writers, including "Eugene Onegin," but what does it for me is Pasternak.

Interestingly, what really got me to understand Pasternak was Thomas Merton's very long essay on him in his book, "Disputed Questions." That made me go back and re-read "Dr. Zhivago" from a poet's viewpoint, and that really turned my head.

Interestingly, Rainer Maria Rilke and Nikox Kazantzakis, two of the past century's geat mystic poets, both visited Russia around the turn of the last century, and both said they were strongly influenced by what they experienced in Russia, and both claimed a lifelong influence thereafter.

As a composer, I allow that I probably fall into the French-Russian-Japanese experimental lineage far more than any other Euro lineage, in terms of who's influenced me.

My husband just came by as I was reading you post - re-reading your post, Jim - and he asked, as if he didn't already know, 'Have you read Anna Karenina?'

'In my spare time I said.'

No, I haven't read the book.

'You should' he said. 'It's a great book.' Mu husband has read them all including War and Peace.

I've read excerpts but never managed the lot. The Russian literature I've read extends to Gogol's Overcoat - brilliant, Solzehnitzen-One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and Dostoyevski's Crime and Punishment - when I was young.

Recently I've heard an audio recording of The Brothers Karamazov. And of course there's Chekhov.

I'm ashamed to say I haven't read more, but I find I can't get into Russian literature so much these days.

This is an intriguing review, Jim but I find I still do not warm to the man, Tolstoy, not so much his writing - but the man I imagine from history.

I know it's perilous to judge the past from the present.

Still I'm very keen to see this film , as much for Helen Mirren and Christopher Plummer as for anything else and I'm grateful that you've offered additional insights.

Thanks, Jim.

Yes, I’m like Lis, Rachel, I feel I should apologise for the fact that I have read so few books and from a fairly narrow range of authors. I so wish I was like Art who can read at speed and remember. I simply can’t devour books and as soon as I find myself skipping paragraphs I call it a day. The book I’m reading just now is 444 pages long and I am finding it a real slog. I would honestly hack it to pieces if I’d been her editor. I’m really not a life-is-the-journey kind of guy. I want things in nice tidy boxes and I want my books to get to the point so I can get on with my life or maybe another book.

I know nothing of Pasternak, Art. I don’t think I’ve even seen Doctor Zhivago although I think I have the soundtrack kicking around. Rilke is another one, like I was just saying to Rachel, I can’t think of a thing by him. I’m pretty sure I’ve scanned a poem or two in passing but nothing has stuck so it’s as if I’ve never read him at all. And I think I should have. I keep imagining some mystical entity scowling and going, “Nope, can’t be a real writer if ‘e don’t know Rilke.”

I have a great fondness for all kind of Russian music. I persist with efforts to come to terms with modern European music but it’s a whole wee world of its own that feels like it got stuck in the sixties. I’m listening to some of Tubin’s symphonies today. I got a free CD with a magazine a few years go which featured three Estonian composers – Tubin, Tormis and Tüür – and I’ve kept an eye of for work by them since; Lepo Sumera and Arvo Pärt I already knew about. Needless to say there’s not a lot of their stuff kicking around at the kind of prices I like to pay.

And, Elisabeth, I’m like you, even though he was regarded as a quasi-Christ figure during his lifetime and Christ knows we all have a past we’d like to sweep under the carpet, I still found myself a bit annoyed by him. I felt he was a bit “righteous over much [and] over wise” to quote from Ecclesiastes 7:16. And he was miserable. At least the Tolstoy in the book is. I suspect that Plummer will play a more human Tolstoy and I too look forward to locating a copy of the film one day. I wonder had Jesus lived to be a doddery old man whether his disciples would have taken charge of him the way that Tolstoy’s felt the need to.

Thanks for adding your write up to the Book Review Blog Carnival!

Post a Comment