She wants to be flowers, but you make her owls. You must not complain, then, if she goes hunting. – Alan Garner, The Owl Service

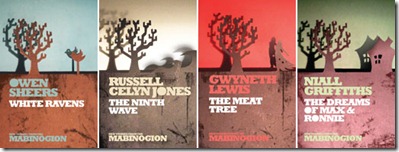

I have never written any science fiction. I love the genre – everything from Douglas Adams to J G Ballard and in between – but every idea I’ve ever had I’ve quashed because it was derivative. I have a first chapter of a novel lying around somewhere and that’s my lot. There really is nothing new under the sun. Everything derives from something else and Gwyneth Lewis’s novel The Meat Tree is no different. It derives from The Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion, Math, son of Mathonwy, a work that is itself highly derivative. Derivative is not necessarily a bad thing. It depends how the elements are combined. A good example would be the TV series Firefly which literally was cowboys in outer space but it worked. The idea was not new; in fact that’s how Gene Roddenberry first pitched Star Trek to the studio, as a “Wagon Train to the stars” and actual Wild West storylines appear in the original series (‘Spectre of the Gun’), The Next Generation (‘A Fistful of Datas’) and Enterprise (‘North Star’).

Lewis’s attempt at combining mythology and future technology is an interesting approach as was her decision to write the entire novel in dialogue. If we’re going to be pedantic the log entries are monologues but the fact is that the whole book is spoken or thought. Of course that’s not new – The Generals by Per Wahlöö is a novel entirely in dialogue, presented as the transcript of the sixteen days of a court martial (though including much of the incidental chitchat as well as the official proceedings) – and it does create its own problems but it also makes the book a quicker read than you think it’s going to be; I read it in a day over three sittings.

The Mabinogi of Math is one of the best known of the eleven tales. It is also one of the more complex. Very briefly, here’s the story:

Math is the king of Gwynedd, served by his footholder Goewin, and his nephews Gwydion, Gilfaethwy, and Euyd. Gilfaethwy and Gwydion contrive to start a war with the southern kingdom of Dyfed so that Gilfaethwy can rape Goewin, and fool Math into leaving the kingdom to lead the army. While gone, Gilfaethwy has his way, and Gwydion steals the pigs of Pryderi. Math, upon learning of the deceptions, punishes the two brothers by using his magic wand to turn them into a series of animals and forcing them to mate with each other. He then takes their offspring to raise them himself. He also seeks for a new footholder, and Gwydion suggests his sister Aranrhod; Math tests her virginity by having her step over his magic wand, at which point she gives birth to Lleu and Dylan. Math then works with Gwydion to counteract Aranrhod's curse laid upon Lleu by creating a wife for the boy out of flowers. Math then drops out of the story, but Lleu becomes the new king of Gwynedd; as Lleu is the son of Gwydion's sister, and Gwydion is the son of Math's sister, and Gwydion is an unsuitable king of Gwynedd, it is logical that Lleu is then made king of Gwynedd. – Jones Celtic Encyclopaedia

Confused? Yeah, me too and I’ve read the book. It’s the names more than anything. Anyway this was Lewis’s starting point but not ours. We only have two characters to worry about: Campion, the outgoing Inspector of Wrecks and his young, female Apprentice, Nona. This is the first time the two have worked together. (Nona: the Fate who spins the thread of life; Campion: a wildflower – not sure how much to read into these.)

Whereas Starfleet captains had to dictate their logs in this future they get to think them:

Synapse Log 28 Jan 2210, 09:00

Inspector of Wrecks

Is that working no, I wonder? I hate these thought recorders. They’re good in very confined spaces, where you don’t want to overhear the idiotic things your colleagues say to their families back on Mars, but I think they’re overrated. But, there we are, I’m Old School. The trick is to keep the unconscious out of it as much as possible and pretend like you’re talking to yourself.

[…]

Apprentice

We’re not one day in and I’m already tired of hearing about the Department of Wrecks in the Good Old Days. When flotsam came in from as far as the Sculptor galaxy or the Microscopium Void. When he had a full team and they got to work on really interesting cultures. Not like this speck from God knows where, just me and him – the one man in the service who has absolutely no imagination.

One of the big problems with all science fiction – and Star Trek: Voyager is especially guilty in this regard – is the amount of exposition and technobabble the writers feel they need to include to help you feel comfortable in the particular universe they’ve created. Thankfully Lewis doesn’t lay it on thick. She treats her readers with a bit of respect and doesn’t feel the need to explain more than she absolutely has to. The grizzled-veteran/rookie-master/apprentice trope is as old as the hills especially where the veteran is on his last mission (think Se7en, Chasing Ghosts, Spy Game or even Men in Black if it comes to that) but that’s fine. (The Star Trek: The Next Generation episode ‘Sarek’ would probably qualify here, Picard

Okay, so we know this is going to be a two-hander (as in DS9’s ‘The Ascent’) set in the confines of a derelict spacecraft (so many but Enterprise: ‘Oasis’ is a good one) in other words a crucible, a contained space in which the two protagonists are going to be tested (e.g. Star Trek’s ‘The Galileo Seven’). What they find is a ghost ship: no crew, not even little piles of white dust where the crewmembers used to be as in the Star Trek episode ‘The Omega Glory’. In other words, the classic locked room mystery, the staple of shows like Jonathan Creek. (The DS9 episode ‘A Man Alone’ is a locked room mystery.)

Synapse Log 29 Jan 2210, 20:30

Inspector of Works

I never expected to see one of these early Earth exploration vessels and in such a perfect state of preservation. It’s like something in a museum. Even the hammocks are intact, as if someone just got up out of them and left them warm.

Missie’s been moaning about having to decipher the ship’s log, it’s a history lesson for her. It’ll do her good to see how space travellers in the past had to work, how uncomfortable it was.

Something’s not right, though. It’s all too perfect.

She

My print reading’s crap but I managed to decipher that the vessel had a crew of three. One woman, two men. That must have been challenging in the days before phero-dampeners. Hard enough working with a man when we’re both shielded from each other’s body chemistry. Two men and one woman, must have been a recipe for disaster. What did they get up to?

He

Where are the bodies? Not even three piles of dust for us to analyse. No sign of forced exit, no breach in the spacecraft’s hull. Nothing for us to go on.

Well, not exactly nothing. There are the VR couches:

Joint Thought Channel 29 Jan 2210, 09:00

Apprentice

VR?

Inspector of Wrecks

Virtual Reality. Before you swallowed the nano-synaptic dream tablets for training and recreation.

Campion decides since the logs contain nothing significant their only option is to explore the virtual world the crew inhabited to try to learn what they can. He explains how it will work to the girl:

Joint Thought Channel 30 Jan 2210, 09:00

Inspector of Wrecks

These old VR helmets can be quite uncomfortable. But it’s more than that. We’re used to VR forming itself automatically to our frontal-lobe profiles, so that it responds to our particular fantasy life. But when the technology started, they still had one person author the programme, so that being inside you’re more a witness than co-creator. You have to take one of the available roles, but the parameters are set by the Mastermind. So the progression of the plot can feel very uncomfortable, especially if you’re not used to it. And until we find out what kind of author we’re dealing with it’s hard to know what it will be like.

Instinctively they go for gender-specific roles: she assumes the role of Goewin, the footholder to King Math, and Campion chooses Gwydion, a magician. But why of all things are they in a Celtic fantasy world? Campion says that they were once all the rage that it was once fashionable to imagine oneself as a Welsh wizard or a Celtic maiden. This I found a bit hard to swallow but then if you’d told me in the mid-nineties that Caribbean pirates and boy wizards would be all the rage in a few years’ time I wouldn’t have believed you so why not a sudden interest in all things Celtic? Still I would have preferred if she’d simplified the names.

From here on in the couple spend more and more time in the virtual world. They don’t stay with the same roles in fact for most of the time Nona prefers to inhabit male personæ. This is quite different from the holonovels in Star Trek. In this virtual environment they have very little leeway. If a character has to go from A to B that’s what they have to do. They can go by the scenic route but they nevertheless have to go.

There is no way even taking into account the space I allow for a review that I can explain this plot – nor would you thank me for it – but let me explain how the tale starts off in more detail than Jones Celtic Encyclopaedia does. Why does Math need a footholder? Are his feet cold? (I’m thinking here about King David and Abishag – see 1 King 1:1-4.) No, that’s not it. He needs to rest his feet in the lap of a virgin or he will die. Presumably he has been cursed but it’s never explained. That is simply how it is. There is a loophole, however, he can walk about normally only during a time of war.

So what do you do if you’re in love with a woman who spends her days with an old guy’s feet in her lap? It’s sure to make courting her a bit awkward. That’s the problem facing Math's nephew Gilfaethwy who has fallen in love with Goewin. The solution is a simple enough one: start a war. That’s where his brother, Gwydion, comes into the picture. Gwydion tells his uncle about animals that were new to Wales called pigs and how he could get them from their owner, Pryderi of Dyfed. Long story short – they end up going to war over them. This leaves Goewin’s lap unattended and, if I can draw another biblical comparison, Gilfaethwy does to Goewin what David’s son Amnon did to Tamar: he rapes her. Which means that Nona gets to experience the whole thing.

When they return this time they both take male roles, the two brothers, Gilfaethwy and Gwydion, to see what Math’s punishment will be when he returns to find out that his footholder is no longer a virgin. As punishment he banishes his nephews, turning them into a breeding pair of deer for a year, then a pair of wild boars for the next year and wolves the year after that. In each of the three instances Campion is transformed into the female of the species and ends up being impregnated by Nona who is the male:

Apprentice

Forget about weirdness. This feels so right. I'm swimming a stream which goes through her back, into her body and I feel inside…

Inspector of Wrecks

Mind of a man in a stinking animal…

Apprentice

Mind of the body, as the lichen lays in the moss and the tree sucks sweet water up, like a tide…

Inspector of Wrecks

Passive, like soil, no will of my own…

Apprentice

Till it explodes. And I’m falling, light-liquid, falling back down from a red doe’s haunches.

Inspector of Wrecks

Oh, the shame.

Apprentice

To be complete as an animal, nothing is better. To smell of come.

Inspector of Wrecks

With my brother!

Apprentice

What have I done?

When the calf is born Math transforms it into a boy and the same happens the next two times so by the end of three virtual years the two brothers have produced three children, Hyddwn, Hychddwn, and Bleiddwn. Much to Campion’s surprise he finds he quite enjoys experiencing life as a female even if that female is an animal:

He

What’s amazing … in all this, is that the sensations of being a mother were so much more sophisticated than they should be, given the primitive VR equipment we were wearing. I can’t understand it. How did I know to lick the fawn’s faeces and urine in order to hide his scent? It’s as if instinct was wired into the game in a way I can’t explain.

[…]

I was horrified when Math turned the boy into a human child. That made it real, somehow. While we were in the forest, we were just animals. I was glad when Math sent the boy away to be baptised and fostered.

I wanted nothing to do with the creature.

In Deep Space 9 security chief Odo, of course, transforms often into a whole menagerie of animals.

Campion and Nona continue to play the game and, as they do, they begin to lose themselves to the various roles they inhabit. Day after day goes by and they still seem no closer to finding out what happened to the original crew. Little by little things start to change and the truth becomes clearer. Are they both too far gone by this point to save themselves?

Of course there’s plenty of instances in Star Trek where people have become possessed and/or obsessed (‘The Game’ for example) but the episode that closest to this book is ‘Masks’:

Through Data, Picard learns that a being called Masaka is waking, and that the only one that can control her is one called Korgano. One of Data's personalities states that Masaka will only appear once her temple has been built, and provides Picard with a pictogram that can create that temple. Inside the temple, they find the symbols that refer to Masaka and Korgano. Data shortly arrives … wearing a mask he had created earlier with Masaka's symbol on it, and refers to himself as Masaka. Picard has the crew search the database from the structure to recreate a mask representing Korgano, and Picard wears it to confront Data. – Wikipedia

That is basically what’s happening to Campion and Nona although in their case they inhabit ever-changing roles. This reminded me very strongly of Alan Garner’s novel The Owl Service (or at least the TV dramatisation) which was also based on this same branch of the Mabinogi although he concentrates on a later section. In that book three children find a set of plates with an owl pattern on it and begin to take on three of the key roles: Blodeuwedd, a woman created from flowers, her husband, Lleu Llaw Gyffes and Gronw Pebr with whom she has an affair. These personæ are also the last that Campion and Nona inhabit and it’s at this stage in the story they realise what’s going on and it turns out that Campion does have an imagination after all, just maybe not quite as vivid a one as Nona’s and that’s all I’m saying about that.

The big question is: Does Lewis manage to pull it off?

On the whole, yes. For a lot of the time they sound like a couple of TV presenters explaining things for the benefit of the audience at home (which is exactly what they are doing) and it inevitably suffers from being too talky – Lewis has no choice to tell rather than show – but I still got caught up in what was happening and wanted to know how things were going to be resolved. It does take a while to get to where it needs to go which is where the version by Garner wins out because he skips all the stuff at the beginning and cuts to the chase. The two books actually will probably be about the same length. Lewis’s feels longer but a good chunk of those 240 pages is taken up by white space. Garner uses the extra space to beef up on character development.

As a standalone science fiction novel (measured up against something like Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris) it’s not a classic; it feels like a novelisation of an episode of The Outer Limits and I’m talking about the nineties relaunch not the sixties originals: perfectly watchable, reasonably high production values, ties everything up neatly at the end but missing something.

As an adaptation of the source material and an introduction to it the book does a pretty decent job and I would think those who have to study the original text would find this a most pleasant way to start to get to grips with the text because that’s what Campion especially is trying to do and he takes us along with him.

***

In 2002 she published her first non-fiction book, Sunbathing in the Rain: A Cheerful Book on Depression, which chronicles her ongoing battle with depression and alcoholism. This is also the subject of collection of poems Keeping Mum - Voices from Therapy. Having agreed to change their lifestyles for their own good, Lewis and her husband bought the small yacht Jameeleh, and having taught themselves to sail set out to cross the Atlantic Ocean to Africa. The journey inspired her 2005 book Two in a Boat – The True Story of a Marital Rite of Passage.

Lewis composed the poetry that adorns the front of the Wales Millennium Centre in huge lettering: Creu Gwir fel Gwydr o Ffwrnais Awen / In these Stones Horizons Sing. Lewis became the inaugural National Poet of Wales in 2005, handing the mantle over to Gwyn Thomas in 2006. She is also a librettist, and has written two chamber operas for children and an oratorio, The Most Beautiful Man from the Sea.

In 2010 Lewis was given a Society of Authors Cholmondeley Award recognizing a body of work and achievement of distinction. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, a Vice President of the Poetry Society and an Honorary Fellow of Cardiff University.

Niall Griffiths

Niall Griffiths