Intuition is the clear conception of the whole at once – Johann Kaspar Lavater

One poet who has strong opinions on the place of intuition in poetry is Jorie Graham who, in interview, had this to say about the role of intuition and how to read a poem:

Our educational philosophies at present are so desperately specialised, so goal-oriented, we have forgotten that when we teach children we are not teaching content, or even "methods for learning," but rather that we are helping a child's intuition and emotions learn to operate in tandem with his or her conceptual intellect--stoking curiosity, that miraculous power that brings desire to bear on the mind. You can do this through any subject matter. And you effect different variations of that synthesis, that awakening, via different disciplines and fields of knowledge, to be sure. When you give a child poems (remembering, once the silence closes back over the end of the poem, not to ask "what does this mean?" but rather, "what did you feel?" or "what did you see?"), you are opening up different parts of his or her reading apparatus than fiction or drama or journalism open up. In fact, at present, only some forms of advanced science – particle physics for example – allow a young mind to experience the paradox, ambiguity, irrational thought, associative "leaping" any good poem teaches us to think and feel in. It opens those synapses in the brain. It always has. Once open, such minds can think differently in any field.[1]

And in another interview with Thomas Gardner:

JG: I’m often asked, in a kind of aggressive way, why the surfaces have to be so difficult in these poems. Or why I so admire surfaces like The Waste Land’s, or Berryman’s, or Ashbery’s. I think it’s because a resistant or partially occluded surface compels us to read with a different part of our reading apparatus, a different part of our sensibility. It compels us to use our intuition in reading, frustrates other kinds of reading, the irritable-reaching-after kind. I agree with Stevens’s dictum: “the poem must resist the intelligence almost successfully.”

TG: You’re asking us to read differently?

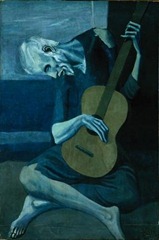

JG: Pollock’s larger murals provide a good example of the process. Because they are painted in such great detail, if you stand far back enough to “see” the whole painting – its wings as it were – you can’t see the actual painting. But the minute you get close enough to see the painting, the dripwork, you can no longer see the whole canvas. Or not with frontal vision. But you can pick up the rest of the painting with peripheral vision – which is, of course, a more “intuitive” part of the seeing apparatus. I think he was doing this consciously – that he was trying to compel us to stand at that difficult juncture of whole and partial visions, subjectivity and objectivity if you will – or at least view-from-above and view-from-middle – historical distance and the present moment – and use our whole seeing mechanism... As with Pollock’s surface, poems with resistant surfaces frustrate frontal vision long enough to compel the awakening of the rest of the reading sensibility – intuition, the body. To my mind (to my hope) that creates a more whole reader, the dissociated sensibility restored to wholeness by the act of reading. Perhaps you could even say the male and female both suddenly awake in you...

TG: There’s some risk in that for the reader, isn’t there?

JG: Yes, because the whole culture requires us to shut that other part down in order to survive – the intuitive, the female, whatever you want to call it. So that it seems to me a very useful political act to write poems in which the resistance of the surface compels that other aspect of our sensibility awake.[2]

The quote from Wallace Stevens is from a poem, the whole of which reads:

Man Carrying Thing

The poem must resist the intelligence

Almost successfully. Illustration:

A brune [brown] figure in winter evening resists

Identity. The thing he carries resists

The most necessitous sense. Accept them, then,

As secondary (parts not quite perceived

Of the obvious whole, uncertain particles

Of the certain solid, the primary free from doubt,

Things floating like the first hundred flakes of snow

Out of a storm we must endure all night,

Out of a storm of secondary things),

A horror of thoughts that suddenly are real.

We must endure our thoughts all night, until

The bright obvious stands motionless in cold.

The 1927 Nobel Prize laureate Henri Bergson argues that knowledge of the world is cultivated more through the intuition than through rational, analytical investigation. “From intuition one can pass to analysis,” Bergson writes, “but not from analysis to intuition.”[4] I suppose it makes sense. If a poem is created by the conscious mind’s acting on something the unconscious provides – call it a writing prompt if you will – then it would seem reasonable that to decode a poem you also need to allow the unconscious its time with the words so the idea of reading a poem and getting it there and then is rendered impossible. Is that what Stevens means when he writes in that final stanza:

We must endure our thoughts all night, until

The bright obvious stands motionless in cold.

that we literally need to sleep on it, to allow our unconscious time alone with the words? In the wonderfully named ‘Holiday in Reality’ Stevens includes these lines:

to be real each had

To find for himself for his earth, his sky, his sea.

And the words for them…

We all have to make every poem we read our own, in fact we are incapable of not making every poem we read our own; we are co-creators or, at the very least, we are the finishers and polishers. We make them shine. In an essay comparing Shakespeare and Stevens, Dan Schneider noted this:

Great poems work intuitively, more often than not, to convince the undermind that what it says is something the undermind has always known. It allows the reader to feel, briefly, that they have co-authored the poem. But when a poem is obviously another’s thought it is much more difficult to get the reader lulled & gulled into that co-participation, & thereby a sense of possession of the work – to be willing to defend it.[5]

This is, of course, in line with Samuel Johnson’s adage: "A writer only begins a book. A reader finishes it." If that is true for novels then it is doubly so for poems.

Stevens wrote the poem in 1945, in direct response to his Ceylon correspondent Leonard van Geyzel's request that he explain "the genuine difficulty that arises out of the enigmatic quality that is so essential a part of the satisfaction that a good poem gives."[6]

It is noteworthy that he adds in the modifier ‘almost’ because, in doing so, what he is saying that intelligence should be resisted, yes, but not defeated. “Resistance is the opposite of escape,”[7] wrote Stevens in ‘The Irrational Element in Poetry’, and in the same essay:

One is always writing about two things at the same time in poetry and it is this that produces the tension characteristic of poetry. One is the true subject and the other is the poetry of the subject. […] In a poet who makes the true subject paramount and who merely embellishes it, the subject is constant and the development orderly. This is true in the case of Proust and Joyce, for example, in modern prose.

The nature of poetry is something that preoccupied Stevens more than most poets. In the twenty second section of ‘The Man With the Blue Guitar’ Stevens shifts the perception of his poem to the subject of poetry:

Poetry is the subject of the poem,

From this the poem issues and

To this returns. Between the two,

Between issue and return, there is

An absence in reality,

Things as they are. Or so we say.

But are these separate? Is it

An absence for the poem, which acquires

Its true appearances there, sun's green,

Cloud's red, earth feeling, sky that thinks?

From these it takes. Perhaps it gives,

In the universal intercourse.

What he is proposing is that ‘poetry’ and ‘poems’ are two different things. In his essay ‘Frost and Wallace Stevens’ Todd Lieber has a crack at paraphrasing Stevens’ opening lines:

[T]he poetry of the subject, whatever the subject might be, is the true concern of the poem. Within the poem itself there is “an absence in reality” because the poem is not dealing with things as they are but with their potential usefulness as instruments of discovery. But is the poetry of things really separable from the things themselves? Is it accurate to say that the poem withdraws from reality when it in fact asserts the reality of the poetry of things? In the interaction of imagination and reality the poem draws on things as they are; perhaps it also gives to them new forms and shapes, new structures of intelligibility.[8]

In poetry Stevens can give reality certain qualities that are otherwise absent, like a thinking sky, and earth that feels and a green sun which brings us, logically, to Robert Lowell’s dictum: “A poem is an event, not the record of an event.”

Description is revelation. It is not

The thing described, nor false facsimile.

So wrote Wallace Stevens in ‘Description Without Place’. The thing about words, which is why we need to take great care in their selection, is that they do do more than merely describe. Works evoke. They provoke. They are never up to the challenge. They are always, always, always inadequate. A poem is a crippled thing really. It needs us desperately. We have to get involved.

The limitations of words are revealed in his poem, ‘On the Road’ which begins with:

It was when I said,

"There is no such thing as the truth,"

That the grapes seemed fatter.

The fox ran out of his hole.

You. . . You said,

"There are many truths,

But they are not parts of a truth."

Then the tree, at night, began to change,

and then a couple of stanzas later adds…

"Words are not forms of a single word.

In the sum of the parts, there are only the parts. The world must be measured by eye";

I, as you can tell from the title of this blog, have long had a love-hate relationship with the notion of truth. I don’t believe in truth-with-a-capital-t except as an ideal and, as such, I don’t believe in a word-with-a-capital-w, a Logos, if you will, that can unlock the Truth even though that is exactly what the Bible talks about, a Word through which all things (and therefore all truths) came into existence. And yet truth still captivates me. If I had hold of it I’m sure it would feel lacklustre. Like the girl you’ve always lusted after, when you finally do get your grubby little paws on her she’s just a girl; she doesn’t have anything different to any other girl.

Truth is best kept at a discreet distance, something to be glimpsed peripherally. In ‘Landscape with Boat’ Stevens muses a little more on the nature of (poetic?) truth:

It was not as if the truth lay where he thought,

Like a phantom, in an uncreated night.

It was easier to think it lay there. If

It was nowhere else, it was there and because

It was nowhere else, its place had to be supposed,

Itself had to be supposed, a thing supposed

In a place supposed, a thing he reached

In a place that he reached, by rejecting what he saw

And denying what he heard. He would arrive.

He had only not to live, to walk in the dark,

To be projected by one void into

Another.

In my poem ‘Broken Things’ – the one I wrote for my wife – I write:

Some things don't

need a how

or a why.

It feels like a platitude. It’s meant to. But it is also me owning up to my limitations. I don’t know why I love my wife. That I cannot articulate the reason does not invalidate the feeling. On the surface the poems of Wallace Stevens that I’ve highlighted here look like intellectual exercises, things to puzzle out. Well, in a way they are but who says that all the puzzling and working out has to be done consciously?

There are clearly limits to reading and writing. There comes a point in every text that one has to move beyond the words themselves. “There is a point at which intelligence destroys poetry,”[9] Stevens wrote in a letter to Ronald Lane Latimer in 1936. I think he is right if one qualifies that statement and reads ‘intelligence’ solely as ‘conscious reasoning’. He also wrote, to Hi Simons in 1940, “once a poem has been explained it has been destroyed.”[10] The poems that mean the most to me are poems that I have allowed to affect me over time. Yes, poems like ‘Mr Bleaney’ provided me with an aha moment but that wasn’t the end of things. Really that was the beginning because it made me realise there was something there to pursue further.

What I’ve realised from what little research I’ve done so far is that Wallace Stevens is a poet I need to investigate further and his Collected Poems is now in my Amazon shopping basket.

Which bring me, finally, to something called intellectual intuition. A contradiction in terms? Perhaps. It’s all a matter of perspective. Are left and right contradictory? Are male and female contradictory? They can be but they don’t have to be. They can be complimentary. In his short article on intellectual intuition psychotherapist Mel Schwartz notes that…

There is a spirit of masculine energy in intelligence, whereas intuition is thought to be a feminine attribute. This divide becomes furthered even more with the fragmenting of the brain's functions into left and right hemispheres.[11]

He is also of the opinion that “intellect and intuition as differing aspects of the same process. When we incline heavily toward one at the cost of the other, we limit our field of vision.”[12] Needless to say his is not the only opinion. The philosopher Schelling called intellectual intuition "the organ of all the transcendental thoughts" whereas Frithjof Schuon said:

In principle, every man is capable of intellection, for the simple reason that man is man; but in fact, intellectual intuition—the “eye of the heart”—is hidden under a sheet of ice, so to speak, because of the degeneration of the human species. So we may say that pure intellection is a gift and not a generally human faculty.[13]

Of course once we bring eastern philosophy and new age thinking into play the whole thing gets very, very confusing although some of the terminology is wonderful: noetic experiences, transrational thinking, paranoesis, emphatic knowledge. I make no bones about it, the more I read the more confused I got and if anyone out there understands this stuff (Art, I’m talking to you) please don’t try and explain it to me; it makes my head hurt. That said I kept coming back to what Schuon said. In an unaccredited article on the subject of intellection in the Gallup Management Journal the author had this to say:

The theme of Intellection does not dictate what you are thinking about; it simply describes that you like to think. You are the kind of person who enjoys your time alone because it is your time for musing and reflection. You are introspective. In a sense you are your own best companion, as you pose yourself questions and try out answers on yourself to see how they sound. This introspection may lead you to a slight sense of discontent as you compare what you are actually doing with all the thoughts and ideas that your mind conceives. Or this introspection may tend toward more pragmatic matters such as the events of the day or a conversation that you plan to have later. Wherever it leads you, this mental hum is one of the constants of your life.[14]

and I don’t know about you but that pretty much describes me: I like to think. I’m not always consciously thinking about something, I’m just thinking. When Schuon uses the term ‘intellection’, and other thinkers do this too so he’s not alone, it appears that he’s using the term as a synonym for intellectual intuition. I’ve decided how, as a poet, I think. I have no idea if anyone else thinks like me – it’s not as if we can measure this – and the term ‘holistic thinking’ makes sense to me. Now, I have no idea if I’ve heard that expression before or if I just invented it but the fact is that it was too good an expression not to have been thought up and defined before me. And it has:

One of the most common distinctions in the literature on cognitive style is between analytic and holistic styles. Analytic thinking involves understanding a system by thinking about its parts and how they work together to produce larger-scale effects. Holistic thinking involves understanding a system by sensing its large-scale patterns and reacting to them.[15]

I would call that seeing the bigger picture. He continues:

Holistic people often excel in social situations requiring sensitivity, intuition and tact. Their ability to get a general feeling about a situation may open their minds to subtle nuances of complex situations. Using computer jargon, a holistic person might be regarded as a parallel processor. That would be the case if a correct response evolves out of widespread simultaneous activity instead of resulting from a controlled, step by step process.[16]

Everything boils down to semantics I find. And this is where words let us down again and again and again. In 1988 I wrote the following poem. It’s not the greatest poem I’ve ever written but its inclusion here makes an important point:

Changeling

It is true that every

seven years we change.

Turning fourteen I started

thinking poetry.

I am now twenty-nine and

safe for six more years.

15 December 1988

I know what I meant when I said I started “thinking poetry” when I was fourteen. I still think poetry. Between August 1991 and April 1994 I didn’t think poetry. I thought like I assumed other people thought, like my dad thought. Who knows how anyone else thinks but I was convinced within myself that I had lost a level of thinking that I had had access to before. Some people might like to mysticise that but just because it was a mystery to me why it was going on (or not going on as the case may be) doesn’t mean there wasn’t a good reason why I was able to think poetry in the first place. I just don’t want to pull it to pieces in case I can’t put it back together again.

I don't know

how clocks work

or time works

or hearts work.

And I don’t know how I work but I work and I’m glad that I do.

REFERENCES

[1] ‘The Glorious Thing’, Jorie Graham and Mark Wunderlich in Conversation, American Poet, Fall 1996

[2] ‘Jorie Graham & Thomas Gardner in Conversation’, Regions of Unlikeness: Explaining Contemporary Poetry.

[3] What Stevens originally jotted down in his collection of aphorisms ran quite simply: "Poetry must resist the intelligence successfully." The modifier, 'almost', was clearly an afterthought. (see Bart Eeckhout, Wallace Stevens and the Limits of Reading and Writing, p.27)

[4] Henri Bergson, An Introduction to Metaphysics.

[5] Dan Schneider, Shakespeare, Stevens, & The Problem With Greatness

[6] Bart Eeckhout, Wallace Stevens and the Limits of Reading and Writing, p.27

[7] Kermode, Frank and Joan Richardson, eds., Stevens: Collected Poetry and Prose, p.785

[8] Todd Lieber ‘Frost and Wallace Stevens’ in Edwin Harrison Cady, Louis J. Budd, eds., On Frost, pp.104,105

[9] Holly Stevens, ed., Letters of Wallace Stevens, p.305

[10] Holly Stevens, ed., Letters of Wallace Stevens, p.346

[11] Mel Schwartz, Intellectual Intuition

[12] Mel Schwartz, Intellectual Intuition

[13] This is taken from a transcript of a 1995 interview.

[14] ‘Intellection’, GALLUP Management Journal, 12 September 2002

[15] Dr. Russell A. Dewey, ‘Cognitive Styles’, Psychology: An Introduction, Psych Web

[16] Dr. Russell A. Dewey, ‘Cognitive Styles’, Psychology: An Introduction, Psych Web

[17] Jan Smuts, Holism and Evolution

“From intuition one can pass to analysis,” Bergson writes, “but not from analysis to intuition." Bergson is right—which is why one cannot write creatively based on theory. Theory (in literature, if not in science)is always secondary—a mere response to created works. Our current infatuation with theory is how we end up with stupidities like "uncreative writing" and "conceptual writing."

ReplyDeleteI agree with Joseph's comment here. The very idea of "intellectual intuition" is absurd, but it's what I have come to expect from poets who get too bound up in theory. As for Jorie Graham, I'd respect her opinion more if I thought her poems lived up to her ideas about poetry, but I don't think that they do.

ReplyDeleteI've resisted commenting at all here as I don't want to be the wet blanket. But Joseph is correct to quote Bergson, and to point out why these oh do logical discussions about intuition oft run aground precisely because it's the rational mind trying to container intuition, which it can't. If it could, we'd all be Great Poets, but we're not.

When other writers deal with this topic I'm left baffled, especially when a poet decides to write a poem that's a test-case, an enactment of the conflict. I like reading about Stevens' poems more than I like his poems, though sections of his work sound cute. Graham likewise, though less so.

ReplyDeleteIn practise, don't throw away notebooks and early drafts. You may need to backtrack to them - they may hold the intuitive element that re-writes flatten out.

Re Abstract Art, this was in a recent New Scientist - Get the picture? Art in the brain of the beholder

I expect theories often sprout from intuitive thinking, Joseph. Companies like Google encourage this kind of approach. Only a very stupid joiner would turn up for work armed with only a hammer. I feel that way about writing and I will use all the tools at my disposal. I may not know the names for all of them but that’s neither here nor there as long as I get the job done to my satisfaction. Writing articles like this are fun but I don’t take them too seriously. I never think what I’m doing when I write a poem; I’m too busy writing the damn thing to care if I’m thinking or feeling or intuiting or whatever.

ReplyDeleteAs I say in the article, Art, “Everything boils down to semantics.” I like thinking about this kind of stuff for a couple of days every now and then but although there is technique to poetry I don’t like treating it like a science. It is a thing of wonder and I’d hate for it to lose its wonder. I had a friend once who wrote a poem about a guy pulling a flower to pieces to see how it worked. A flower is not a clock through and putting one back together is not an option once you’ve disassembled it.

And, Tim, there is more than enough here to baffle the best of us. I have both Stevens and Graham on my Amazon wish list. I’ve read enough of each of them to think I might enjoy their collected poems but I’m in no rush for anyone to buy me them. I recently finished a poem that’s been lying in draft for months and a damn good poem it turned out to be too. Why didn’t I see how to end it when I first wrote those opening lines I have no idea. There’s a time for everything and a part of me likes the randomness of the creative process. You pass a house every day of your life on the way to school and then work and then one day something catches your eye and there you have a poem. Why then? Who cares. You can’t control it. You simply have to be prepared for it and respond to the moment.

I’m not a big rewriter though. I tidy up poems but it’s very rare for me to spend a long time rewriting. I did with my last poem and it all turned out well so I don’t set hard and fast rules. I don’t think you can, not if you’re a real poet.

I hate the lenses that take pictures like the one scene seen in your first image. It reminds me of of the images taken by sophisticated cameras cleverly posited with perfectly shaped reflective spheres. It allows cameras to be at all kinds of crazy out of direct lines of sight angles. Like the the convex mirrors to look around corners in hallways leading to surgery.

ReplyDeleteThanks to algorithms not much more complicated than progressive multi-application and di-vision the nonsense distorted image taken with a camera that can be behind two walls. As long as the line of sight has a free path, the cameras vision can walk around multiple 179 degree corners as long as ball bearings are placed as containers telling the line where the 181 degrees are that it cannot go.

I couldn't wrap my head around the rest of what you saying.

well, you know what I mean, always taking the shorter number of degrees in the angle of a circle because anything close to 180 it doesn't even need the reflective sphere and if the angle is only say 350 degrees going clock wise, we both know it isn't going to take the impossible route, it is going to go ten degrees counter clock wise and end up focused on the same point as the objective while the diocese marvels that it is some sort of Hg boson thinking it went the long way around, not thinking it would just walk backwards through Heaven's exit.

ReplyDeleteEven though it told everyone the way it was doing it.

I actually quite like fisheye lenses, who. I’ve always wanted one but I could never justify the cost for the odd photo that might be useable. As for the stuff you couldn't get your head around, I’m sure you’re at the front of a long queue and I’m not far behind you. There’s fun to be had looking at how people try to analyse poetry. I see nothing wrong with it—nothing is unexplainable—but as soon as one man puts forth a theory there will be another ten who want to disagree with him. And all ten will have good points to make. Words are so not up to the task but they’re all we have so we muddle through.

ReplyDelete"Blessings, Stevens" wrote the Welsh poet R S Thomas in admiration of Stevens' skills in one of his own later poems.

ReplyDeleteStevens. The very name like the words - it flows. A cool massage of the mind. It's a wonderful thing.

I’ve come to Stevens late, Gwilliam, but I like what I’ve read so far. I didn’t really set out to research him but that’s where this article led me and I’m quite happy that it did.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you work too, Jim. Man, you've given me a lot to ponder!

ReplyDeleteI've read Stevens on and off for years but it's only been in the last few months that something has finally clicked for me with his poems and I'm enjoying them so much now. Reading them aloud makes quite a difference for me, same with Pound but I'm still not much of a fan of his work.

ReplyDeleteOh, Milo, if you only knew how I struggled. I have a folder on my desktop with articles on cognitive poetics and I simply cannot get my head around what they’re saying. I don’t like to think of myself as a stupid guy but I am sure that there are easier ways to explain a lot of this stuff.

ReplyDeleteAnd, Marion, I’m still not a fan of Pound—apart from his two-line ‘Metro’ poem which is wonderful. As far as the Stevens goes I’ve just ordered a collection of his poems. This one has one of his plays included too.