The word aerobics comes from two Greek words: aero, meaning "ability to," and bics, meaning "withstand tremendous boredom – Dave Barry

The boredom epidemic

Boredom, as we learned in part one, came into existence in the mid-nineteenth century but…

Orrin Klapp documents an enormous increase in the use of the word boredom between 1931 and 1961, calls attention to "the large vocabulary of English words connoting boredom," and hypothesises that this lexicon "not only registers the prevalence of boredom but helps create it."[1]

Modern-day boredom is another beast entirely. It attacks the young and the old, the rich and the poor, the known and the completely unknown. And it’s getting worse:

Fifty years ago, the onset of boredom might have followed a two-hour stretch of nothing to do. In contrast, boys today can feel bored after thirty seconds with nothing specific to do; the threshold has been drastically lowered.

The choices of adolescents, in particular, are prone to inverse intuition. The adolescent mind is nowadays so hyper-stimulated that the absence of stimulation — boredom — is unsettling, while the chaos of constant connection is soothingly familiar. A languishing teenager feels irritable and instinctively knows how to rev up: go online, turn on the TV, call someone, text. Continuous stimulation and communication comprise the new normal. It is a state of being that conflates sensory pleasure with happiness.[2]

Perhaps here though we “need to draw an important distinction between a constructively bored mind and a negatively numbed mind.”[3] No one can possibly be bored after thirty seconds. What they are doing is anticipating boredom.

[T]echnology contributes directly to boredom by bombarding us with a constant barrage of intense stimuli, habituating our brains to a high level of stimulation. When it is removed, we suffer withdrawal. We are addicted to the artificial human realm we have created with technology. Now we are condemned to maintain it.[4]

“The brain is always adjusting to new stimuli,” says Augustin de la Peña, a psychophysiologist who has studied boredom for 30 years. “Once the brain has seen something new a few times, it no longer finds it interesting. The brain’s ante for stimulation is always being upped, just as a drug addict needs larger and larger doses to get high.”[5]

It’s easy to blame the up and coming generation for the change in the world’s perception of boredom but, before we do, think on this:

It is one of the most oppressive demands of adults that the child should be interested, rather than take time to find what interests him. Boredom is integral to the process of taking one's time.[6]

I’m not saying that that attitude can’t be blamed on technology just not digital technology. The prevalence of labour-saving devices especially from the fifties on has inculcated in us the expectation that we can get what we want at the flick of a switch, be it the clothes washed, the dinner cooked or the kids entertained. Boredom is not the problem; boredom is a symptom of the problem.

Kids throw temper tantrums, write on walls, run around naked. They need to be told these things are wrong under most circumstances. Being unstimulated is wrong. We need constant stimulation. If we don’t get it we might become bored and bored is BAD:

A few years ago, cellphone maker Motorola even began using the word "microboredom" to describe the ever-smaller slices of free time from which new mobile technology offers an escape. "Mobisodes," two-minute long television episodes of everything from Lost to Prison Break made for the cellphone screen, are perfectly tailored for the microbored. Cellphone games are often designed to last just minutes -- simple, snack-sized diversions like Snake, solitaire, and Tetris. Social networks like Twitter and Facebook turn every mundane moment between activities into a chance to broadcast feelings and thoughts; even if it is just to triple-tap a keypad with the words "I am bored."[7]

A boring conference

Might boredom be something you’d actively seek out? If you had an opportunity to be bored would you jump at it? In 2010 many did when they learned of an event called ‘Boring 2010’:

Boring 2010 sprang to life when [James] Ward [who edits a blog called I Like Boring Things.] heard that an event called the Interesting Conference had been cancelled, and he sent out a joke tweet about the need to have a Boring Conference instead. He was taken aback when dozens of people responded enthusiastically.

Boring 2010 sprang to life when [James] Ward [who edits a blog called I Like Boring Things.] heard that an event called the Interesting Conference had been cancelled, and he sent out a joke tweet about the need to have a Boring Conference instead. He was taken aback when dozens of people responded enthusiastically.

Soon, he was hatching plans for the first-ever meet-up of the like-mindedly mundane. The first 50 tickets for Boring 2010 sold in seven minutes.[8]

Some of the talks included: ‘Like Listening to Paint Dry’ during which William Barrett listed the names of every single one of 415 colours listed in a paint catalogue; others discussed ‘The Intangible Beauty of Car Park Roofs’ and "Personal Reflections on the English Breakfast; Ward himself gave a PowerPoint presentation about his ties.

Journalist and author Naomi Alderman spoke about the difficulty of having to observe the Jewish Sabbath as a child. Her talk, ‘What It's Like to Do Almost Nothing Interesting for 25 Hours a Week,’ ended on an unexpected, touching note. "When we learn to tolerate boredom," she said, "we find out who we really are."[9]

I’m not sure I would go to a conference like this but I have listened to a guy describing the joys of watching paint dry . . . or it might have been wood warp.

Another quote from Huxley:

Your true traveller finds boredom rather agreeable than painful. It is the symbol of his liberty – his excessive freedom. He accepts his boredom, when it comes, not merely philosophically, but almost with pleasure.[10]

I don’t usually jump to provide quotes from Yahoo! Answers but when someone asked what the above quote meant this was one of the answers:

What I think it means is that one can find pleasure in boredom because it is a luxury; you can only be bored if you have the time and freedom to do what you please. The corollary is that those who are never bored probably don't get a chance to have any time to themselves or to consider what they want to do with their time: they're too busy doing what they have to do to survive.[11]

What struck me about this is that is very much how boredom was once viewed as evidence that you were someone if you could afford to be bored. The king could be bored and be boring but woe betide you if you let on you were bored in his presence.

Boring art

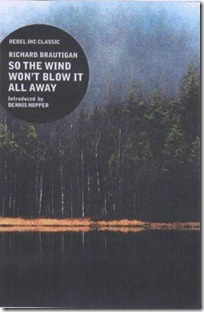

The thing is there is something attractive about boredom. I’m not drawn to boredom as much as I am to sadness but I cannot pretend there is not a strong pull. Here are a few lists of boring books (according to the opinion of the authors of these lists at least): Lee Rourke's top 10 books about boredom, The Best Boring Books, The 15 most boring books, Most Boring Books of All Time (Bleak House makes that one). They are all completely subjective of course.

The thing is there is something attractive about boredom. I’m not drawn to boredom as much as I am to sadness but I cannot pretend there is not a strong pull. Here are a few lists of boring books (according to the opinion of the authors of these lists at least): Lee Rourke's top 10 books about boredom, The Best Boring Books, The 15 most boring books, Most Boring Books of All Time (Bleak House makes that one). They are all completely subjective of course.

Why write a boring book though? I make no apology: every idea I get for a new book is boring. In my third novel almost the entire action takes place in a park and much of that simply sitting on a bench for forty years. I read a review today of With the Flow by J.K. Huysmans which is described as follows:

Huysmans' story is of a government employee battling against, and finally resigning himself to, the all-powerful ebb and flow of social forces. It describes the minutiae of misery and boredom in a day in the life of a man who – for a moment – refuses to go with the flow.[12]

and I would have ordered it there and then if I didn’t have so many unread books already. I like empty photographs and paintings – Hopper is a great favourite. I find them calming. There is enough stuff happening in my head without asking it to compete with busy pictures. I enjoy minimalist music: give me Arvo Pärt’s Für Alina over Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie any day of the week. Andy Warhol said, “I like boring things.”[13] I like boring things too as long as they don’t bore me in a negative way.

[I]n Brian O'Doherty's 1967 Object and Idea [he talks about] "high-boredom and low-boredom art." High-boredom art relies heavily on exhaustible optical effect, such as with op and Pop art. Low boredom art, the realm of artists like Donald Judd and Robert Smithson, does not force itself onto viewers and outside of the gallery. In fact, the sculptor and critic (a.k.a sculptor Patrick Ireland) writes, "It tends to fade into the environment with a modesty so extreme that it is hard not to read it as ostentatious."[14]

Samuel Beckett is boring. He would not deny it if he was alive today. Martin Amis blames him for the modern trend in “unenjoyable” novels:

It all started with Beckett, I think. It was a kind of reasonable response to the horrors of the 20th century – you know, 'No poetry after Auschwitz'.[15]

Ironically perhaps the word ‘boredom’ is not used very often in Beckett’s literary works, the main exception being in Company in which there is a long discussion regarding which position of the body is the least boring. To understand Beckett though you have to understand Beckett’s view as to what the opposite of boredom is. In his study of Proust he wrote this:

Suffering represents the omission of that duty [habit], whether through negligence or inefficiency, and boredom its adequate performance. The pendulum oscillates between these two terms: Suffering – that opens a window in the real and is the main condition of the artistic experience, and Boredom – with its host of top-hatted and hygienic ministers – must be considered as the most tolerable because the most durable of human evils.[16]

For Beckett being bored is the best it gets. Boredom is meaninglessness, ergo life, at its best, is meaningless; the rest is suffering. He wasn’t the first to come up with that idea though. Germaine de Staël is quoted as saying, “One must choose in life between boredom and suffering,” but as she died in 1817, and spoke French, I doubt she used the word ‘boredom’.

[Beckett’s] ‘theory of meaning’ is essentially this: There is no personal meaning, and all other meaning only becomes paler and paler until it is a nothing. What else is there to do than to wait or hope for a new meaning? The problem is that the waiting for meaning, for the moment, is endless. A real understanding of human existence has to be based on a fundamental absence of meaning.[17]

Didi and Gogo wait for Godot to give their lives Meaning-with-a-capital-m and extract as such meaning-with-a-small-m as they can from the process of waiting for him. So many of us look outside ourselves for meaning: to God, to relationships, to jobs, to everyday events, tasks and routines.

HAMM: We're not beginning to... to... mean something?

CLOV: Mean something! You and I, mean something! (Brief laugh.) Ah that's a good one!

Did and Gogo, and Hamm and Clov, don’t lie down to boredom, not without a fight anyway. That struggle is often painful to watch – particularly in Endgame – but that is the point. And throughout both plays there are lulls when it looks like boredom is going to take control – transition vacuums – when, even if they don’t say the words, you know they’re thinking: What are we going to do now? We all hit these after bouts of activity. You spend four years writing a novel and then it’s done and then what are you going to do with your life? The term for this is transition boredom. The cause of the boredom is academic – it could just as easily be impatience – the sensation is always the same. Just like a drowning man will struggle against the waters that are engulfing him so a bored man will struggle to fight boredom – imagine being at a boring lecture: you sit up straight, take notes, try to stop your mind from wandering – but eventually he will enter the second phase:

In this state, all contents disappear, internal and external as well, all reality disappears, all everydayness and the man, according to Heidegger, touches pure existence. For a single moment, boredom reveals the true being, taken outside any categorical, substantial or subjective levels. Everydayness steps asunder, presenting the being itself.[18]

Beckett found Heidegger’s language “too philosophical for”[19] him. He was, after all, by his own admission “not a philosopher”[20] and so I don’t think that where we leave Didi and Gogo, at the end of Waiting for Godot, and Hamm and Clov, at the end of Endgame, is perched on a moment of insight, rather they are – metaphorically at least – unalive (in the sense used by Erich Fromm when he wrote: “[B]oredom is nothing but the experience of a paralysis of our productive powers and the sense of un-aliveness”[21]) not that, when you look at Beckett’s later plays, death necessarily means the end of suffering.

Beckett found Heidegger’s language “too philosophical for”[19] him. He was, after all, by his own admission “not a philosopher”[20] and so I don’t think that where we leave Didi and Gogo, at the end of Waiting for Godot, and Hamm and Clov, at the end of Endgame, is perched on a moment of insight, rather they are – metaphorically at least – unalive (in the sense used by Erich Fromm when he wrote: “[B]oredom is nothing but the experience of a paralysis of our productive powers and the sense of un-aliveness”[21]) not that, when you look at Beckett’s later plays, death necessarily means the end of suffering.

This is not so hard to grasp. People say that they have no lives when obviously they are alive and moaning at us. When we say that what we mean is that we don’t know what to do, or are unable to do, anything without lives which ties in with what Fromm said above. Think about your life as some kind of mechanism that you can hold in your hand. You can pick it up, poke around with it, take it to bits, put it back together again, but it doesn’t mean anything until you figure out what it’s purpose is or assign a purpose to it: an Enigma machine would make a perfectly good doorstop, for example.

I have talked before about how I believe meaning to be the province of the reader (or, in the case of art, the viewer). It is the responsibility of an artist or a writer to create the right conditions to enable the right reader or viewer to make contact with that meaning. Talking mainly about photography Agnė Narušytė had this to say:

The spectator’s role is crucial in the aesthetics of boredom. Only an intentional and competent spectator can penetrate the initial effects of monotony and banality and reach other, more profound, layers of meaning. Firstly, he or she has to read the signs of opposition to the tradition of representation which offers new models for understanding art. The indeterminacy of meaning encourages intuitive perception, involvement in the process of creating meaning, and tarrying in front of the work of art.[22]

A great many artists have exploited this. In fact, in 1949, John Cage made it an imperative:

The responsibility of the artist consists in perfecting his work so that it may become attractively disinteresting.[23] (italics mine)

So, if something is not interesting, if it does not hold our interest, does it mean it’s boring?

Unfortunately, interest is a short-lived phenomenon. It is quickly exhausted. The interesting becomes boring. As soon as it is no longer topical, as soon as the brief, orgasmic instant during which it disguises boredom is over, it too enters the realm of the boring, making way for boredom in all its unpasteurized purity.[24]

Attaining is exciting. Maintaining is boring. Does that mean that “boredom is simply the shed skin of interest?”[25] I think perhaps that novelty is something that needs to be worked through too. Take sexual attraction as a metaphor. When you’re young and horny and all you want to do is have sex with something and pretty much every member of the opposite sex (or the same sex if that’s your predilection), as long as they’re about your age, is a viable candidate and for a while sex is enough, it can fill the void for years, and then one day you take a step back, look at who you’re with, and go, “Eh?” A lot of people might define boring as “no longer novel” and in a world where technology is perpetually offering something newer (and, they tell us, better) I imagine a lot of time we misdiagnose familiarity and think we’re bored when we’re not.

Do you need to be cold to appreciate warmth? Do you need to be lonely to welcome company? Do you need to experience boredom to be able to distinguish between the merely distracting and the truly interesting things in life? Cold is not necessarily bad unless you’re swimming with whales in the Arctic, solitude is not bad unless you’re Robinson Crusoe or Tom Hanks and boredom is not bad unless you’re Kaspar Hauser.

The positive effects of boredom

Colin Bisset draws a distinction between good boredom and bad boredom:

Perfect boredom is the enjoyment of the moment of stasis that comes between slowing down and speeding up – like sitting at a traffic light for a particularly long time. It's at the cusp of action, because however enjoyable it may be, boredom is really not a long-term aspiration.[26]

I like the idea of boredom as a liminal state, a moment of potentiality. It ties in with how I feel about the search for meaning very much. Bisset continues:

Wasn’t Newton sitting underneath an apple tree staring into space, and Archimedes wallowing in the bath, when clarity struck? In my own insignificant way, I think I have always understood that doing nothing is the key to getting somewhere. As a writer, it takes a while to convince others that you are working hard whilst appearing to be lying on the sofa staring at the ceiling, but once this is accomplished it can be very useful, especially if you are enjoying staring at the ceiling and hear, “I’m sorry, he can’t come to the phone at the moment, he’s working” – which suggests a genius on the cusp of a plot breakthrough rather than someone deciding whether to have poached or scrambled eggs for lunch.[27]

Or as Walter Benjamin put it, a little more poetically:

If sleep is the apogee of physical relaxation, boredom is the apogee of mental relaxation. Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience.[28]

Why is this?

In recent years, scientists have begun to identify a neural circuit called the default network, which is turned on when we're not preoccupied with something in our external environment. (That's another way of saying we're bored. Perhaps we're staring out a train window, or driving our car along a familiar route, or reading a tedious text.) At first glance, these boring moments might seem like a great time for the brain to go quiet, to reduce metabolic activity and save some glucose for later. But that isn't what happens. The bored brain is actually incredibly active…[29]

Bored people are more prone to daydreaming and when you daydream your brain goes into problem-solving mode. Research shows that daydreaming is one of the most effective ways to turn on your right brain which is the part responsible for creative insight. Ah, if only it were that simple.

There are those who report positive benefits from allowing themselves to be bored:

Those athletes who run or swim or bike in ultramarathons for eight hours at a time … also testify to what endless repetition can teach in terms of focus and self-discipline. While we are bored, there is time to “strip away our character armour, shed layer after layer of imposed motivations and values and circle closer to our unique essence.”[30] It is a time to stand naked and confront one’s pain without distractions and diversions.[31]

One of the statements Lars Svendsen makes in his excellent book on the subject is:

Boredom is immanence in its purest form. The antidote must be transcendence.[32]

It is a statement that I have struggled to understand. He’s writing that because he’s trying to understand something Roland Barthes wrote, that…

Boredom is not far removed from desire: it is desire seen from the shores of pleasure.[33]

The word ‘pleasure’ has connotations – though to be fair what word hasn’t? – and I find it hard to believe that the purpose of life is simply to experience pleasure but I can’t pretend that what I’m doing this very minute is not pleasurable in its own way. I am trying to turn ignorance into understanding, to go from knowing nothing to  knowing something. That Eureka! moment was so enjoyable that Archimedes streaked (literally) down Syracuse’s high street shouting out, “I’ve found it!” I think that boredom is our natural state and life is all about rising above it: getting out of the tub.

knowing something. That Eureka! moment was so enjoyable that Archimedes streaked (literally) down Syracuse’s high street shouting out, “I’ve found it!” I think that boredom is our natural state and life is all about rising above it: getting out of the tub.

Pleasure is the opposite of pain, even if it’s not necessarily the solution to all kinds of pain. If we’re not experiencing pleasure the fear may well be that we will experience pain. And we may well do:

That we have unprocessed pain inside us, waiting for any empty moment so that it may assert itself and be felt, is not so surprising given that a main imperative of technology is to maximise pleasure, comfort, and security, and to prevent pain. […] Today we go to the pharmacy cabinet to apply technology to the alleviation of any discomfort, no matter how minor. Have a hangover? Take an aspirin. Have a runny nose? Take a cold medicine. Depressed? Have a drink. The underlying assumption is that pain is something that need not be felt.[34] (italics his)

I get a lot of aches and pains. My wife tells me to take a couple of ibuprofen. I do. The pain subsides and I can work. The source of the pain is still there though. The pill is only a palliative. It fixes nothing.

Even the gods get bored…

Did you ever wonder why God created the universe? If you don’t believe in God this is a moot point because who knows why the Big Bang banged but I do remember asking my Dad (when I was interested in such things) why God, who was perfect and therefore complete in himself and in need of no one else, would go to the bother of creating others. There are plenty of scriptures that explain what his purpose was but none that I know of that supports the answer I was given which was: It was God's pleasure that the universe and everything in it be created. Does that mean that God was bored? (Kierkegaard certainly believed so.[35]) If God was, then that implies that boredom is not a bad thing, God being the embodiment of goodness. I don’t know and I don’t really care but what I do know is that as a writer I like the idea of starting with a boring, blank sheet of paper – literally nothing – and, after in this case about 9000 words, having created something. Better yet when the thing created has meaning.

What is the opposite of pleasure? One might have thought ‘pain’ was the obvious answer, but it seems more reasonable to assume, excepting physical pains and pleasures (where most people would simply settle for not hurting as the opposite of pain anyway), that it is boredom “the condition which most thoroughly inverts that more desirable feeling’s modes of existence.”[36]

What do you look for in a mate, whether a marriage mate of just someone to pal around with? You want someone who is like you. I know they say opposites attract but unless you’re magnetic I’m not buying it. I get bored around people who just want to talk about drinking and football and chasing women. Now think on this:

Most people are bored. Why? You asked how to get rid of boredom. Now find out. When you are by yourself for half an hour, you are bored. So you pick up a book, chatter, look at a magazine, go to a cinema, talk, do something. You occupy your mind with something. This is an escape from yourself. You have asked a question. Now, pay attention to what is being said. You get bored because you find yourself with yourself; and you have never found yourself with yourself. Therefore you get bored.[37]

Boredom is the self being stuffed with itself.[38]

It’s an interesting way of looking at boredom. But then again why wouldn’t you be bored with yourself: he’s been everywhere you’ve been, done everything you’ve done, made the same mistakes as you and has learned nothing more than you have from all that. Yeah, I’d be bored with me too. That would be the normal thing to be, the natural thing to do. Now pain is not very nice but it is natural. And your natural response is to get away from it. You fling yourself out of the road or you curl up in a ball or you yank your hand out of the flame. So too with boredom. Boredom is natural but our increasing response to it these days has to be to do something about it. Distractions provide temporary relief – for some reason I can’t help think what the Bible says about the “temporary enjoyment of sin”[39] here – but whatever that temporary relief is, be it a sin or not, it is not the answer to boredom. I believe that meaning is the answer and, as Dorothy Parker put it, curiosity is the means. If we are created in God’s image and out of boredom he created us then it’s only natural for us to want to create things too but we need to be in the right frame of mind, one that has let go of distractions.

If he hadn't been locked up with himself, Martin Luther King would never have written ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail,’ Oscar Wilde wouldn’t have composed his ‘Ballad of Reading Gaol’ and O. Henry wouldn't have turned out his famous short stories (after being sent to prison for embezzlement). Then again, Adolf Hitler wrote Mein Kampf while imprisoned for what he considered to be "political crimes" after his failed Putsch in Munich in November 1923 and Jeffrey Archer wrote the three-volume memoir A Prison Diary, a novel and a collection of short stories. Boredom has a lot to answer for too.

What is the meaning of life? It is one of the great unanswerable questions. After pondering it for years most of us get bored with it and go off and look to solve questions that actually might have answers. Life may not have any Meaning-with-a-capital-m in the grand Beckettian sense but that doesn’t mean there are not lots of other meanings-with-small-ms to be found on the way. I get what-I-call-bored with my writing a lot of the time because it lacks what-I-call-meaning. Boredom is life’s gravity. I cannot fly but I can jump.

***

The title for this article by the way is a quote from Simon Critchley talking about Samuel Beckett’s use of the term “the buzzing” in his play Not I: “This is what I call the tinnitus of existence, the background noise of the world that underlies the diurnal hubbub, returning at nightfall as the body tries to rest.”[40] It seemed appropriate.

The title for this article by the way is a quote from Simon Critchley talking about Samuel Beckett’s use of the term “the buzzing” in his play Not I: “This is what I call the tinnitus of existence, the background noise of the world that underlies the diurnal hubbub, returning at nightfall as the body tries to rest.”[40] It seemed appropriate.

And in case you never worked it out: What goes up a chimney down but not down a chimney up? An umbrella.

FURTHER READING

A Philosophy of Boredom by Lars Svendsen – the complete book is available online

The Boring Institute REFERENCES

[1] Orrin Klapp,

Overload and Boredom: Essays on the Quality of Life in the Information Society, pp.32,33

[2] Adam J. Cox, ‘The Case for Boredom: Stimulation, Civility, and Modern Boyhood’, Atlantis, Spring 2010

[3] Richard Louv, ‘The Benefits of Boredom’, Spark Action

[4] Charles Eisenstein, The Ascent of Humanity

[5] John D. Spalding, ‘Ah, Boredom!’, The Society of Mutual Autopsy, 13 November 2004

[6] Adam Phillips, On Kissing, Tickling and Being Bored: Psychoanalytic Essays on the Unexamined Life, p.69

[7] Carolyn Y. Johnson, ‘The Joy of Boredom’, The Boston Globe, 9 March 2008

[8] Gautam Naik, ‘Boredom Enthusiasts Discover the Pleasures of Understimulation’, The Wall Street Journal, 28 December 2010

[9] Ibid

[10] Aldous Huxley, Along the Road: Notes and Essays of a Tourist, p.17

[11] What is this quote saying? Best Answer

[12] Book Trust

[13] Andy Warhol, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up,p31

[14] A brief history of boredom, activesocialplastic.com, 31 August 2007

[15] Martin Amis, ‘Awards only go to boring books, says Martin Amis’, The Telegraph, 10 July 2011 (The quote is by Theodor Adorno who famously declared that to write poetry after Auschwitz was barbaric and then later recanted what he regarded as a knee-jerk reaction.)

[16] Samuel Beckett, Proust, p.28

[17] Dr Lars Svendsen, A Philosophy of Boredom, p.98

[18] Joanna Hańderek, 'The Problem of Authenticity and Everydayness in Existential Philosophy' in Ed. Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka, Phenomenology and Existentialism in the Twentieth Century: New waves of Philosophical Inspiration, p.194

[19] An interview with Tom Driver in Graver, L. and Ferderman, R., (Eds.) Samuel Beckett: the Critical Heritage, p 219

[20] Ibid

[21] Eric Fromm, The Sane Society, p.179

[22] Agnė Narušytė, The Aesthetics of Boredom: Lithuanian Photography 1980 – 1990, p.17

[23] John Cage, Silence, pp. 64, 88

[24] Henri Lefebvre, Introduction to modernity: twelve preludes, September 1959-May 1961, p.260

[25] Matt Nelson, ‘Good Writing is Boring’, Splice Today, 25 May 2011

[26] Colin Bisset, ‘La Vie D’Ennui’, Philosophy Now, July/August 2011

[27] Ibid

[28] Walter Benjamin, The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov, p.5

[29] Jonah Lehrer, Boredom, scienceblogs.com, 24 March 2009

[30] S Keen, ‘Boredom and How to Beat It’, Psychology Today, May 1977, p.80

[31] Jeffrey A. Kottler, On Being a Therapist, p.171

[32] Dr Lars Svendsen, A Philosophy of Boredom, p.47

[33] Roland Barthes, Das perfekte Verbrechen, p.12

[34] Charles Eisenstein, The Ascent of Humanity

[35] “The gods were bored; therefore they created human beings.” ‘Rotation of Crops’, Either/Or

[36] Joseph Brooker, ‘What Tedium: Boredom in Malone Dies’, Journal of Beckett Studies, Vol. 10, nos. 1-2, p.2

[37] Jiddu Krishnamurti, Krishnamurti on Education, p.59

[38] Walker Percy, Lost in the Cosmos, p.74

[39] Hebrews 11:25

[40] Simon Critchley, Very Little... Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy and Literature, p.xxv

Rhodes was named one of

Rhodes was named one of