The intelligent layman no longer looks to poetry for insights into our times. The only surprise is how poets got away with it for so long. – Tim Love, ‘The Great Poetry Hoax’

On the back of Tim Love's poetry chapbook, Moving Parts, which I bought from HappenStance some months ago and have picked up and put down a number of times over that time, it says of his poems:

His poems challenge perception. Sometimes they aren’t what they seem, but then again, they are. They offer themselves like canvasses in a gallery, the white box of the page inviting the reader in. The process is playful and serious and, like all good art, demands no less than absolute attention.

The average poem is eleven-years-old and earned him nine pounds. Twenty-seven of the twenty-eight poems have been previously published in magazines. It is a good introduction to a literate and thoughtful poet. Some of the poems are straightforward and playful, like the opening poem, ‘Love at first sight’ which, I’m sorry to say, I will now forever associate in my mind with Brotherhood of Man’s ‘Save Your Kisses for Me’ – apologies to all those who are familiar with the song, because it’ll probably be running through your head for the rest of the day; not all first loves are expressions of romantic love. It is a poem that does what all good poets do, it misdirects. I recall another poem once that talked about two brothers I think and it’s only at the end of the piece you realise that the poet is actually going on about a pair of swans. You can read the whole of ‘Love at first sight’ by clicking on the hyperlink if you’ve not already done so but it begins:

You look down. She’s looking at you. You look away. You look again.

She’s still looking. Don’t stare

because she’s beautiful but because

you’re lost in thought. Every moment counts.

The reflection of misplaced lights

reminds you of an art gallery. Don’t touch,

stare.

Art and art in galleries in particular is a recurring theme in this collection; five other poems mention them and if I was searching for an alternative to the word ‘collection’ then it wouldn’t be unreasonable to describe Moving Parts as a gallery of poems. Of course discounting the actual pages none of the parts move, but parts will move you. And parts will move you to put the pamphlet down and go and do something else instead. And that’s fine. I’m sure Tim would say that was fine, but he’d hope that the next time you find yourself wandering through his gallery of poems that you might stop and linger a while in front of the more difficult poems.

Back in 1998 Tim wrote an essay entitled ‘Not so Difficult Poems’ which begins as follows:

First there is a mountain

then there is no mountain

then there is.An academic criticised this as being at best nonsense. In fact it's a reference to an old Chinese text (by Lao Tzu?[1]), pointing out that if you analyse something, you may lose sight of the original object, but later, the object returns richer than before. However, what the text doesn't point out is that before you study a piece you need to realise it is difficult and that it's worth the effort. The critic found these words from a Donovan song difficult because they're deceptive – neither the context nor the content give the readers any hint that work is required. This demonstrates one of the many types of difficulty prevalent today, but not the most difficult to deal with. It's just a matter of finding the "missing key".

The opening poem in the collection lulled me into a false sense of security because I turned the page and found: ‘Iron Birds’ which I struggled with despite the fact it’s only ten lines long. I wandered away. Came back. Tried again. Still locked. Checked my pockets – no key. Mooched off again. Don’t worry, I’ll get back to it later down the page.

I decided to simply plough my way through the collection, just get to the end and see how the overall shape felt, see what themes revealed themselves. Galleries and art crop up in several poems as I’ve said, as do bridges (including the wonderful

I'm happy to going along with Valéry. Though I've read little of his poetry, I've read quite a lot about him and like his attitude.

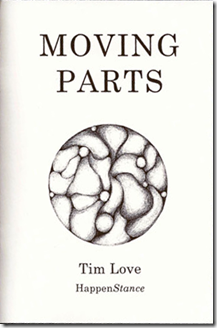

Then I looked a little closer at the image on the cover and wondered what the hell it was supposed to represent. An image of bacteria perhaps? So I asked Tim:

The cover was the first that Helena [Nelson] suggested (from some pictures she already had, I think). She offered some others later, but I preferred the first. It shows parts on the move, and has an organic/artificial/lab mix that suits the book's material.

Language, of course, fascinates Tim. Can’t imagine a writer not captivated by language. One of the most striking poems in the collection is ‘The Fall’ where he tracks the transformation of language over the past 6000 years:

Spanish and Portuguese split 600 years ago,

Sanskrit and Greek 4000 years before,

So there must once have been

a common tongue, a first kiss

Now American and English have split and…

a fire engine that used to hee-haw

like a seaside donkey goes wow wow wow

“Words are too significant,” writes Tim, in ‘Misreading the signs,’ “too few, unable to describe without pointing or denying, / their meaning flicked like abacus beads as we scan.” The poem is set in an art gallery and Tim is obviously asking us to compare how we look at art and how we look at poetry. This is something Tim addresses in one of his essays, ‘Attention, Agility and Poetic Effects’:

Reading often doesn't proceed linearly through the text. Even in prose there's typically 10% of saccades (eye-movements) backwards. In poetry this percentage is likely to be higher. In particular ambiguity and confusion will provoke backtracking or regression to lower layers. The amount of backtracking needed will influence the reading strategy.

I hadn’t really thought about it until I read it here but I do find myself flitting back and forth over poems in the same way I do works of art for example, to backtrack to ‘The Fall’, when I read “London leaves fall / yellow as cabs” I found myself diving back to the line “American and English split months ago” because, as everyone knows, London’s taxis are black. This is an obvious connection but it highlights the fact that these poems work in layers.

In ‘Action at a distance’ Tim writes: “words aren’t the world / but they take us where we want to be.” In just the same way as Newton’s flawed mathematics “got us to the moon and back” these flawed tools serve us but only up to a point and that point is where our imagination steps in and ably demonstrated by his son blowing “gunsmoke from his fingertip” and then playing dead.

In an article about aging written about a year ago Tim writes:

I'm not very autobiographical and have never depended on intense inspiration or imagination. I think I've become more efficient at finding and exploiting material. Who knows, I might even be improving with age...

I might have disputed that until I learned that he has two boys, Sam and Luca, so the daughter in the opening poem and ‘Mark’ in ‘Taking Mark this time’ are creations, although I have little doubt that he remembered his own children when writing the poems.

…as I chase the night into

the cul-de-sac of dawn, cities closing the distances between them,

one or other claiming every village like young lovers, greedy

I carry him still sleeping to his bed, his doll eyes

Briefly opening. He’s only four, only everything.

But just as birth opens the collection old age and death are not far away from the dying swan in ‘Touch’

Further on, the lockmaster told me it was no use

phoning anyone; if I could touch it,

it would be dead by morning.

via “the toothless sucking / [on] moon-flavoured sweets” in ‘Estuary’ to “the darkness flapping / so close to you, so huge” in ‘Crows’ nests’, the final poem in the collection.

Tim’s fascination with art is obvious. There are references to Van Gogh, Munch, Turner, Mondrian and Vermeer, in fact his poem ‘Misreading the signs’ is set in Amsterdam where the poet shelters from the rain in a gallery (presumably the Rijksmuseum) where he finds himself transfixed by Vermeer’s Woman with a Water Jug:

Causality becomes patter, a loss

of narrative where viewpoints fail to accumulate – Vermeer’s

yellow moment expands to fill a postcard, calendar or jigsaw.

Now I have to wonder if one of the signs that Tim is misreading here is the name of the painting, because Woman with a Water Jug (on the right) was the first Vermeer to arrive in America circa 1887 and currently resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. There is a painting in the Rijksmuseum which also depicts a woman with a water jug but it’s called The Kitchen Maid (on the left).

He doesn’t make the same mistake (assuming this was a mistake) in ‘He understands but he doesn’t love’ – the only piece in which was previously unpublished – which opens:

So here I am, in the famous Chinese Room.

If you’re thinking of galleries or palaces

you don’t understand.

I thought I was being clever here assuming the setting was the room designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh in the Ingram Street Tea Rooms, Glasgow. That said, examples of Mackintosh's room design, furniture and fittings are now on display at Glasgow's Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, effectively replicating the room, although that all happened probably years after this poem was written, I would imagine. I was, however, wrong. In an entry on his blog Tim writes:

The title's a quote about Picasso (by a fellow artist, I think).[2] The Chinese room is a thought experiment by philosopher John Searle. A person in a room receives slips of paper through a slot. The paper has squiggles on it. The person looks these squiggles up in a book which has instructions on what to scribble on a piece of paper that's pushed back through the slot.

Unbeknownst to the person the squiggles are Chinese and the notes being passed out are reasonable responses to the received messages. The people outside think that the person in the room understands Chinese. Does s/he? Does "the room" understand? If not, what does? How can you tell? How much do you understand of what you say?

And then, as in any other gallery, I found myself back in front of that painting, or, in my case, that poem:

Iron Birds

You lay out words to tempt them,

another poem about poetry.

Rhyme radio valves with light bulbs.

Rewrite airstrips with painted decoys.

Ancestors can't save you. Burn your foodstores.

Murder the medicine men. Empty your shelves.

You have seen them flying overhead.

They will come again. You will write about

how their vapour trails are like the broadening,

fading scratches on your lover's back.

My wife has an expression that I’ve adopted since it’s a good turn of phrase: the ‘decoder ring poem’. I’ve written about them before; they’re poems where there is a missing element and it’s impossible to make complete sense out a poem without being in possession of that ‘key’ or ‘code’. Some poems are like Fort Knox; every line holds secrets if only you can find yourself on the same wavelength of the poet. I’d like to meet the person who sat down and read Tim’s poem, ‘Closure’, which is not in this collection, and got it first, second or even third time. Have a crack at it and then look at his notes.

In his article ‘Attention, Agility and Poetic Effects’, which I quoted from above, Tim goes on to mention:

A literary work has many features, some of which might be considered as "layers". For example, Roman Ingarden developed Aristotle's concept that a literary work of art has at least four layers[3], starting with sound, then sense. Perceived properties (like beauty, difficulty, etc) can slide from one level to another. In an experiment by Song and Schwarz where people were shown recipes in different fonts[4], a recipe in a font that's hard to read was thought to be harder to execute than the same recipe in an easy font. Similarly, speed of reading (controlled by layout) can affect the perceived speed of the narrated events, and a surprising layout can be synchronised with a narrative surprise.

[…]

Upper layers can have emergent features absent from lower ones (emotions only exist at higher levels) or can have effects that contradict those of lower layers (a story full of jokes can be sad). Interpretation is not a straightforward progression from lowest to highest level. A higher level interpretation can provoke a re-interpretation of a lower level.

All of the above suddenly makes reading a poem feel like a very difficult thing indeed. In his article entitled ‘My system’ Tim outlines what he expects from a reader. It’ll take up too much space to address all of them but these two jumped out at me:

- When someone reads a text they will try to make sense of it using explicit or implicit instructions about how to combine the text's components. Readers will bring their knowledge to the text, but the context within which they meet the text matters too.

- The reader experience takes priority over the author's. If the author decides to give two characters the same name because they had the same name in real life, that's not helpful. If a poem came into being as an exercise in syllabics, but the reader gets nothing from the syllabics except puzzlement re the line-breaks, that's not helpful.

Let’s go back to ‘Iron Birds’. This is what I got out of it:

The title reminds me of the expression the native Americans used to use to describe trains, ‘iron horse’ and I suppose had there been planes in their day that’s what they would have called them. I’m not sure if I made this connection before I read the words ‘ancestors’ and ‘medicine men’ but it’s there now. When you talk about laying out words to tempt them I remember the old joke about an Irish woman trying to feed a helicopter bread. The birds symbolise the passengers, the so-called ‘jet set’ if that expression still exists. No one reads poems on planes. And they are even less likely to read ‘modern’ poetry where people think it’s okay to ‘rhyme radio valves with light bulbs’. What is poetry to these ‘birds’? Airstrips are where planes land (fall to earth literally and metaphorically) but why the decoys, to distract them, to force them to crash? Is that what happens to people who try to read ‘difficult poetry’? Do they get ‘fed’ with decoys and not real food? If the birds are the readers then the ‘you’ who sees them must be the writers. Are writers cruel? If they hurt their lovers they are. How are the scratches inflicted? Because they are selfish and only write what makes them happy? The great writers that have gone before us, their reputations can’t excuse us. We need to destroy the crap we have been writing that we say has power but, like the medicine men of old, our words only have any power if people believe in them and not always then.

I sent that to Tim and he directed me to his post Notes about ‘Iron Birds’ where he wrote:

[W]hen technologically advanced cultures visit more primitive, isolated ones, they often give presents. After the visitors leave, a religion might develop in the hope of getting more presents, based on rituals – building imitation landing strips and planes, or imitating the behaviour of people with walkie-talkies, etc. The title alludes to the primitives' impression of planes. Some isolated poetry writers are being compared to Cargo Culters. The poem begins:

You lay out words to tempt them,

another poem about poetry.Later they're mockingly told to "Murder the medicine men. Empty your shelves." (medicine men are the wise men, the lecturers; shelves can have both food and books). At the end the hopeful visions of vapour trails are compared to scratch marks fading on a lover's body.

I personally think the poem would have been better served with the title ‘Cargo Cult’. That is the missing key. Personally I think a poem that doesn’t contain all the necessary elements for a reader to work it out on his or her own is a bad poem. For me, ‘Iron Birds’ is a bad poem because it fails to meet my needs and expectations. Tim writes:

The variation between readers can be attenuated by writers. For example, a writer can hint at something in a way that few people might notice. Later the writer can be more explicit for the readers who didn't get it the first time.

For me he didn’t do enough here. I wasn’t alone. In her review of the collection, although not talking about this particular poem, Sue Butler writes:

When friends take me to an exhibition of abstract paintings, I stand in front of each one whispering to myself, Don’t look for narrative. Don’t look for narrative, hoping that eventually I will see something I recognise.

[…]

To my frustration, I can hear things rattling throughout this pamphlet that I can’t fully understand or grasp firmly enough to fully appreciate. I’ve hammered and hammered on the glass but I just can’t open up a crack.

In poetry though we are told to make every word count and so there is rarely an opportunity to open up a text later on, especially not one only ten lines long. In this poem there is no later. I sent a copy to a fellow poet in New York and asked him to see what he made of it and he did no better than I did but I like the way he put it:

I'm more, I don't know, annoyed after being told what it's about than I was before when I did (and KNEW I was failing) the best read I could.

That’s it. Exactly! I also knew I was failing as I was reading it. Well said, that man. I don’t mind failing in front of a piece of abstract art because I’m not an artist, but I mind failing in front of a poem.

Back in 1997 Tim did something quite brave. He reviewed his own collection which, at the time he had intended to call Misreading the Signs – he couldn’t remember when I asked him why the name change. And the review is not all gushy and glowing either. A wise man, to get in there first before the critics. Whereas I honed in on ‘Iron Birds’ he picks on the next poem in the collection, ‘Giraffe’, saying:

‘Giraffe’ [uses] imagery at the expense of sense, symptomatic of a more general conflict between feeling and intellect that is not always well resolved.

I am not sure I would have been brave/stupid enough to include that poem. I struggled with ‘Iron Birds’ but at twice the length I gave up on ‘Giraffe’ completely. (In an e-mail to me Tim described the piece as a “‘Martian Poetry’ metaphor-fest.”)

These two or three poems aside I actually enjoyed this collection. I had to spend far more time with it than I am used to. That is not a criticism of the poetry but a confession on my part: I don’t often read or even try and read chapbooks like this because they require and deserve more time that I find I can spare. I need to do something about that; I really do.

I like Tim Love. I have no particular reason for liking him – our paths cross rarely, we pass the time of day and then trundle on our way – but he’s someone I find I can relate to. I was never employed full time as a computer programmer but I did work as a database designer for several years. He’s also been writing for about the same time as me. His first poem was published in 1972 in a school magazine, the same year as me; Tim is two years older than me. His first collection wasn’t published until 2010; mine was the same. He also writes the kind of articles I aspire to and publishes them on a variety of sites, Litrefs, Litrefs Reviews and Litrefs Articles but also check out the list at www2.eng.cam. Seriously, if you’re an inexperienced poet and are fed up dumping raw emotion on the page and calling it poetry this is the guy you should be reading. I would have given my eye teeth when I was nineteen to have access to the kind of articles he writes. Probably the main reason I like him is that, when he was younger, he looked like my one-time best friend, Tom. Stupid reason to like anyone but there you go.

Moving Parts is available from HappenStance for £4.00 + postage but if you want to sample more of his poetry for free just click on the following links:

- ‘The New World’ (with notes)

- ‘Fossil Exhibition’ (included in Moving Parts)

He has also produced some small videos to accompany some of his poetry which you can view here.

***

His poetry and prose has appeared in many magazines. He won Short Fiction's inaugural competition in 2007. More detailed information can be found here.

REFERENCES

[1] The proverb goes: “At first, I saw mountains as mountains and rivers as rivers. Then, I saw mountains were not mountains and rivers were not rivers. Finally, I see mountains again as mountains, and rivers again as rivers” and is credited to Hsin Hsin Ming

[2] A Japanese artist, Riichiro Kawashima, once asked Henri Matisse what he thought of Picasso. Matisse answered, "He is capricious and unpredictable. But he understands things."

[3] According to Ingarden, every literary work is composed of four heterogeneous strata:

- Word sounds and phonetic formations of higher order (including the typical rhythms and melodies associated with phrases, sentences and paragraphs of various kinds);

- Meaning units (formed by conjoining the sounds employed in a language with ideal concepts; these also range from the individual meanings of words to the higher-order meanings of phrases, sentences, paragraphs, etc.)

- Schematized aspects (these are the visual, auditory, or other ‘aspects’ via which the characters and places represented in the work may be ‘quasi-sensorially’ apprehended)

- Represented entities (the objects, events, states of affairs, etc. represented in the literary work and forming its characters, plot, etc.).

[4] Hyunjin Song and Norbert Schwarz, ‘If It’s Hard to Read, It’s Hard to Do: Processing Fluency Affects Effort Prediction and Motivation’, Association for Psychological Science, Vol. 19, No. 10

Because I'm not a poet, I feel ill-qualified to comment here, but what strikes me now most firmly is the idea of being prepared to read into difficult writing. It's rather, as you describe, like looking at an abstract painting and tryng hard not to look for narrative.

ReplyDeleteI'm always looking for narrative but it need not be complete. For me I like to resonate to images and scenes. If I can imagine something in my mind's eye, however incomplete, that's almost enough.

I'm not a great reader of poetry. I only ever got far enough in my poetry writing days to pour that raw emotion out on the page.

I tend to prefer prose because it's okay to use more words.

To me poetry is demanding, however well and clearly expressed. When I read a poem I expect to be in for a struggle, much as you describe. The struggle to find meaning.

Thanks for a terrific post, Jim.

Who said you have to be a poet to read poetry, Lis? I sometimes feel that that’s the case though, the only people who appreciate poetry are the ones who write it and that’s certainly not the case with prose. I struggle with poetry all the time despite the fact that I’ve been writing it for forty years. It’s why I take the time to research things like flarf because I want to understand the mindset of the people who write that way but, more importantly, I want to understand how to read it. If I’m not supposed to look for some kind of narrative in a poem then what is left to me? We humans are hard-wired to look for meaning in everything which is why people see the Virgin Mary in all these wonderful places.

ReplyDeleteI think I probably tried to cram too much into this article. I used Tim’s booklet as an excuse to write it but I was more interested in making people aware of Tim’s existence online. His articles on writing (poetry and short stories mainly) are nothing less than a treasure trove and I would have been over the moon to have been handed them when I was eighteen or nineteen and beginning to get serious about my writing. Too many good poets get stuck at the emotion-dump stage of writing; they think that is what poetry is. And it can be so much more. Technique is not a dirty word. Technique enhances.

You've really piqued my interest in Tim's poetry with this one, Jim. I am going to get this book. No shadow of doubt. I'm not 100% convinced that at the end of the day I'm going to get from it all that I'm hoping for, but I might. He seems likely to go off on some exploration I would not have thought of as a subject for a poem - and that's enough for me. For starters, anyway.

ReplyDeleteIn your defence, Dave, I’m not sure there’s anything you wouldn’t have a crack at writing a poem about judging by your recent efforts. I think, for me, the most important thing about Tim’s poetry and its variety is that Tim is someone one can learn from. And I’m always keep to learn. I believe very strongly that if poets want poetry to survive they need to be willing to share what they know. Some will be unresponsive and be perfectly happy to dump raw emotion on a page and call it poetry and that’s fine but then there will be people like I was when I was eighteen or nineteen, desperately interested in the technique of poetry but unable to access much information on how I could be writing. The only magazine at the time was the wonderful Poetry Information which is where I first read essays on poets like William Carlos Williams and Basil Bunting; I didn’t even know these men existed. And don’t get me started on women poets I didn’t know existed. I honestly don’t think I read a single poem written by a woman while I was at school. Thank God for the Internet.

ReplyDeleteI'm a fan of "The Truth About Lies" and feel honoured to be mentioned here.

ReplyDeleteI have trouble big-time understanding some poetry - see my write-up of The Best British Poetry 2011 for example. But I have trouble with prose too. Is "even the dogs" easy or Beckett's "How It Is"? What about Borges? I think my prose (I've a booklet coming out soon) can be at least as baffling as my poetry.

Poetry perhaps brings into starker focus what it means to "understand". Do you understand "Do not go gentle ..."? Do you understand a melody (some poems are melodies)? Do you understand "Name of the Rose" or did you just like it, not realising how much you'd missed (with some poems there's no surface to like if you don't understand the depths)? If you like Escher, Magritte, etc, do you have to be able to articulate your understanding of them? Explain why van Gogh's "Sunflowers" is better than a photo of the same scene.

For her "Perfect Blue" book, Kona MacPhee wrote some bonus material about each poem. I've written about a few of the poems online. I intended to write about a few more.

You make valid points, Tim. I’ve always been a little embarrassed by my love of Magritte’s art – I am a long-time fan – because I don’t understand it on any kind of intellectual level nor, to be fair, do I try to (with the possible exception of The Treachery of Images). I think what frustrates me about my understanding of understanding is that I feel it needs to be complete, that it has moved on from knowledge. I know about Eintein’s mass–energy equivalence but I don’t understand it; I couldn’t explain the formula or build on and I most certainly don’t have the wisdom to use my knowledge in the right way.

ReplyDeleteI fully understand that it is up me to complete a piece of writing. I accept that. But I’d like to think that my additions are those the writer would have expected me to make and I’ve not forced the writing out of shape to conform to my own ideas. I struggle endlessly with Beckett’s later prose works but knowing as much as I do about the man and also being familiar with his creative arc, from being a mini-Joyce right down to being lost for words in ‘What Is the Word’, I am willing to make more of an effort. I know that there is reasoning behind what he is doing even if I can’t quite reach it.

And I felt exactly the same about ‘Iron Birds’. I knew there was something missing that would unlock the piece. And there was. It was just the wrong poem for me or I was the wrong reader for it. Do you have to have studied Dante inside and out to get all of Beckett’s constant nods? No, but a knowledge of Dante will certainly enhance one’s appreciation of Beckett. That is where I think ‘Iron Birds’ falls down, because too much depends on that key, for me certainly. Larkin’s ‘Mr. Bleaney’ works without knowing anything about its author or the fact that it was written in Hull and there is also the point that sometimes knowing too much about an author or the circumstances surrounding the writing can actual ruin a piece.

I have the Kona MacPhee book by the way. She is on my list of poets to highlight and I’m overdue getting to her but, hell, you waited long enough.

Though I don't write poetry, I enjoy reading it. I love the images brought to life in a poem. Many poets can express so much in few words.

ReplyDeleteI haven't finished your review yet and I am already running late but I will be back, wanted to thank you for the part on "saccades" as I was having to take tylenol when I read from all the squinting, and now just moving my eyes back and forth real fast makes the in between words just like a motion picture.

ReplyDeleteI can't believe i used to read by squinting. Thank you Jim!

As the cost of RAM and disk storage has decreased, there has been a growing trend among software developers to disregard the size of applications. Some people refer to this trend as creeping featuritis. If creeping featuritis is the symptom, bloatware is the disease. I tend to think about these huge novels that people write like this, Rachna, they just write and write and write and never think about the poor people who have to read what they’ve written. I remember the composer Holst saying that a composer’s best friend was an eraser so this is a mentality that doesn’t just apply to writers. And there are poets out there too who write fifty lines when twenty would do. I started programming with a ZX Spectrum and the total memory was 48 kilobytes but it’s amazing what you can do with 48K and a bit of imagination. I think of poems that way. Just because I have a blank page there’s no need to fill it.

ReplyDeleteAnd, who, the whole saccades thing was completely new to me. I’m afraid I am no scientist. But I like the idea that people don’t read in straight lines. I find that interesting.

Four things jump out at me on reading your book review today. (1) your mention of what “jumps out” at you in poetry; (2) some readers’ acknowledged “need for narrative” in a poem, (3) the idea that people need to understand (“get”) what they’re reading/seeing; and (4) the perception that people “look for meaning in everything”. Interesting to me were the thoughts that arose about one's approach to, expectation of, and resonation with certain poems/fiction/art. (Wow Jim, 55 embedded links! Kept me busy for a while.)

ReplyDeleteThanks for the intro to Tim Love’s articles. I’m devouring them as I write. Already I’ve found some insight into wonderings arising from your review: namely:

Frustration at the difficulty some poems present:

Tim’s take on it: “Obscurity may sometimes shield the charlatan but without it we might lose a valuable opportunity to transcend words, a loss we can't afford.”

On meaning in a poem: “It doesn't need to have meaning to be beautiful.” [I would add, “or be understood to resonate or have poetic impact.” I'm thinking Wallace Stevens here, whose metaphores "jump out at me", whose meaning I can't grasp, but keep going back. And I can't articulate why, except by using the terms "vibration" and "connection".]

Thanks, Jim and Tim. A true pleasure and great find today.

oops. That should have read "or be understood or resonate to have poetic impact." How multitasking can cause fumblings. :)

ReplyDeleteI confess I have not given your post the attention it deserves, so my comment is perhaps a little premature. I did find your analogy of abstract art/some poetry quite telling. I think I tend to approach both in the same undisciplined way: I am moved by the dynamics and colour, swept along by line, and sometimes I feel I grasp some deeper/higher meaning, while at other times I try to simply absorb and mull.

ReplyDeleteOn a different matter, yours was the first blog I read, ever. I was posting s piece about Alan Bennett and found your excellent posts about him. From there I found Dave King and numerous others.

I feel a little awed and thrilled when you leave a comment on my blog - as I never anticipate such a visitor.

Thanks, Isabel

Fifty-five links, eh? You really didn’t have to click on every on, Annie. I tend to be a bit heavy-handed with hyperlinks. When I wrote all those Wikipedia articles it got me in the habit and I like the idea that I don’t have to explain everything in the body of the article itself; they’re long enough as it is besides a lot of my articles are intended as jumping-off points and this is typical of that style. I’m only introducing you to Tim’s world. If he touches a chord with you the links are there to save you have to wade through Google looking for stuff about him; I’ve done that for you.

ReplyDeleteI have mixed feelings about this article. I personally think I’ve crammed too much into it for a single article and I should have done here what I did with Marion McCready, a two-parter, but this is how all my notes came together and so that’s what I posted.

The subject of difficult poetry deserves its own post and I’ve been thinking about doing one for a while. I’d like to come to its defence but in my heart of hearts I find that I can’t. No one has yet been able to sell me on it and I don’t trust things that can’t be explained. In the old days when you went into a shop the salesman knew the specs of the product and so could talk with confidence about its pros and cons; they were users themselves. Nowadays I’m always half-convinced that they’re making stuff up, saying whatever they think I want to hear so that I’ll buy the damn thing and go away. What few defences of difficult poetry (or poets) that I’ve read have always made me doubt the expertise of the person doing the defending, as if they’re struggling for words and often compensate by using too many making me feel as if they’re trying to bamboozle me and I wonder what their agenda is: why are they trying to sell me broken goods?

Every poem should come with a warning – ‘Some assembly required’ – because that’s the nature of the beast but IKEA wouldn’t sell a fraction of the furniture it does now if there weren’t instructions in the boxes and we were left to guess what went where. That’s how I feel about most so-called difficult poetry and how do you tell the difference between ‘difficult’ and ‘bad’?

Meaning is a huge topic. It comes in two flavours as far as poems go: denotation and connotation. Denotation is when you mean what you say, literally. Connotation is created when you mean something else, something that might be initially hidden. And it isn’t an either/or situation, especially in poetry. The issue for me is how much to assume our reader has available to enable them to decode what has been encoded. Show a photo of Marilyn Munroe to a kid these days and they’ll denote ‘woman’ or maybe ‘lady’ whereas you or I will also connote ‘sex symbol’ and at a deeper level we see her as a symbol of the myth of Hollywood. I would have no problems referencing Munroe in a story or a poem and expect the majority of my readers to connect at some level with why I’ve used her. Mentioning Melchizedek would be another thing completely: Noah, Moses, Jesus, Adam, Abraham, yes, but not Melchizedek. For most people that would come under the heading Esoterica. And the same with cargo cults. But this is a topic for another time I think.

I hope you told Dave King and Elisabeth Hanscombe that you were awed and thrilled by their comments too. There’s nothing special about me, Isabel. I’m like most people. I capitalise on what I’ve learned and shy away from subjects that will expose my many, many, many weaknesses and limitations. As far as abstract art goes I just think the museum scene in L A Story puts the whole thing into perspective; there’s a similar scene in Woody Allen’s Play It Again Sam.

ReplyDeleteGlad you enjoyed the Alan Bennett articles. I think he’s fairly well known these days but not so much his early work. This is something that troubles me about television, the fact that great works get shown once or twice and then forgotten. Episodes of Dad’s Army get repeated ad infinitum ad nauseum but what about the early plays of Dennis Potter, Harold Pinter and Alan Bennett? One of my earliest blog posts was about this: What God knows about TV drama.

I, too had great difficulty accessing good - especially current - poetry all through my teens. And that despite of going to a Grammar School, where you might have thought they'd have been abreast of affairs. But no, the winds of Eliot and co had not blown through their corridors. Somehow an essay or two on Pound came into my hands and that was the first I knew of contemporary poetry. And now you mention it - no female poets at all!

ReplyDeleteEvery now and then I stumble across school sites, Dave, where they list what they’re studying and it’s clear that things are changing. The music courses include popular music for example whereas all we covered was the history of classical music and even there once we got into the 20th century things tailed off with the Second Viennese School. I remember my teacher mentioning in passing and with some disdain a work that only had one chord in it (which I assume was Terry Riley’s In C and her definition is a gross oversimplification) but we never got to hear it and God alone knows that she would have made out of John Cage’s 4’33” of not playing a musical instrument.

ReplyDeleteAs far as modern poetry goes we did get a very brief introduction to Lawrence Ferlinghetti. A student teacher (who looked for like Ginsberg than Ferlinghetti I have to say) tried to get us to discuss one of his poems with little success but he was only there for one period and then it was back to the usual.

Well. I wasn't going to comment here, but I've read your review three times now, and found there was something to say after all. No doubt I'll sound like a broken record.

ReplyDeleteThere are two problems with puzzle-box (decoder ring) poems: 1. They're often obscure for the sake of being obscure, which is no good thing in poetry; it leads to the sort of overly-intellectual head-game poetry that a lot of contemporary poets think is what they ought to be doing, whether they like it or not. 2. Once you've figured out the gimmick and decoded the poem, what more is there? why go back and re-read the poem again? Once you've figured it out, it's done.

I completely agree that poems have layers: layers of experience, of meaning. Where I disagree is that these are somehow programmable (I use that word deliberately) by the poet. It's not only that the reader might discover meanings that the poet wasn't aware of, it's that the poet might also have put in meanings to be discovered later. If the poet allows for something other than left-brain control, sometimes archetypes are found in the poem that some other part of his mind put in there. Those are sometimes what gives real depth and resonance to the poem. It's why we go back to re-read Rilke, etc. We always find more layers.

A lot of poets also seem to believe in this contemporary myth, that poets write for other poets, and not for other readers. That only encourages puzzle-box writing. it's one reason poetry has become over-intellectual, and left the blood behind (thanks to Ken Armstrong for the analogy). Technique and craft are not dirty words, no—except when they dominate the writing, and dictate it. Technical writing exercises are like five-finger piano exercises: not music in themselves. What craft does do is allow us to analyze and articulate our understanding of writing, and how it works. (Or art, or music.) That's purpose of art theory: being able to articulate what we can find in the art. So I don't buy the idea that technique exists for its own purpose: that's just more head-games. Technique exists to serve the poem, not control the poem. Theory is great at describing what the poem does, but not very good at dictating what the poem ought to have done. Technique is wonderful—as long as it is kept in balance with actually having something to say.

And there are understandings of art and life that are not on the intellectual level, that are just as valid as the intellectual response. I keep coming back, here, to the problem that this sort of poetry is written by people who live in their heads, and often forget they have bodies. As just one example out of many, Francis Bacon's art wasn't intended to provoke an intellectual response, but a gut reaction. A lot of critics have a hard time with Bacon because they can't intellectually explain it away.

Whatever it is I wish I could bottle and market it, Ken. Carrie is doing her final proofread of Milligan and Murphy this week and then it’s off to the printer. Every now and then she’ll stop and read a bit of me back to me as if to reassure me that I can actually write. And that’s nice. What I like even more if when she titters while reading and I can’t resist asking what it is she’s found so funny. I was asked in an interview recently if I could have written one book which one would I have chosen and Billy Liar was the obvious choice. It works as a play, a book, a film, a musical and a TV series.

ReplyDeleteAnd, Art, I agree that this is something that poets of all levels need to consider seriously. Technically proficient poets are often deliberately obscure, inexperienced poets are frequently obscure by accident. The result is the same, a reader who is left with missing (possibly essential) elements. I do not believe that the intention of the poet in either case is for their reader to find the key and, once found, game over. Once you have the key you proceed into the poem as per normal; you wind it up with the poetic key and the poem-machine does its stuff. I have no problem with their being a key and often the key to unlocking my poems is in the title, an excellent place to hide a key and underused by most poets including me.

Where I have a problem is where specialist knowledge is required to unlock a poem. My wife has a poem called ‘Orbs’ which was read to a bunch of scientists if memory serves right (she’s having her nap so I can’t check) and they got it immediately; it’s as clear as mud to me. Is it a bad poem? No – it does what it was designed to do, and well – but its audience is limited and she accepts that. It’s the same with poems written for individuals. Other people can get something from them but it will never alter the fact that the poem was not written for them.

I get the point you’re making with Bacon. The literary equivalent would, of course, be Beckett’s Not I which is designed to “work on the nerves of the audience, not its intellect.”

"You look down. She's looking at you."

ReplyDeleteThat's a good line for a swan. Or a pair of swans.

If Tim republishes his book I have a better cover for him. I shall put it on my blog in a while.

I assume by now, Gwilym, you’ve read the whole poem and see that it’s nothing to do with swans. Nice photo though. That said, I can’t really imagine a swan taking a bad photo. Unless it was dead or something horrible like that.

ReplyDeleteJim, I knew instantly that it wasn't about swans. That was your incredible muse effect! You had me immediately reaching for my photo album. George Szirtes does it for me too. He's another special muse for me. Peter Finch also.

ReplyDeleteJust read Art's comment, which to me is such a terrific explanation of the uses of craft, technique and theory - tools and not the finish product or the reason for being.

ReplyDeleteThanks Jim for providing Art with the inspiration to write this.

It's a bit difficult for me to comment on this topic without looking as if I'm defending my stuff. So here goes!

ReplyDeleteThe publisher asked for "Iron Birds" (she'd seen it published), so I sent it in my first pamphlet submission. The piece wasn't meant to be a puzzle, or even obscure. It was supposed to be a poem comparing "poetry about poetry" (or even puzzle poems) with Cargo Cults. It was written in 1992 and published pre-2000, I think. My guess is that since then (because of satellite dishes and changes in US military strategy), Cargo Cults and awareness of them have faded. In general I didn't want to revise published poems for the pamphlet. Perhaps in this case I should have. Perhaps there should have been notes in the book, but notes about this poem are online for those who need them.

I often moan about obscurity. But many poems that used to seem obscure to me no longer seem so, (or like fog in a painting, I no longer see it as something that obscures the "real" work). I'm also much less wedded to the "poetry as communication" idea than I used to me.

Art wrote: There are two problems with puzzle-box (decoder ring) poems: 1. They're often obscure for the sake of being obscure. [...] 2. Once you've figured out the gimmick and decoded the poem, what more is there? why go back and re-read the poem again? Once you've figured it out, it's done.

To which I'd reply: 1. Obscurity (like euphony, humour, melody, etc) is an effect that can be employed for several purposes. 2. The gimmick is part of the poem, not a wrapper to be thrown away after use. Like a joke or a math proof it may merit re-reading.

Puzzle/Riddle poems have a long tradition. They were quite popular with Anglo-Saxons, I think. For some of the poems, finding the key is a major part of the value of the poem. For others, the key is a minor aspect of the poem, though some readers are easily distracted by such things and give up once they've found "the key". Sometimes the poem's not a puzzle after all. You're sent a jewel box. It's nice, but the bloody thing's locked. You shake it. You don't hear a rattle. You slide a pen-knife under the lid and twist. The lock breaks, but so does the box. There's nothing inside. Shame about the box.

I don’t think you have any reason to defend yourself or your editor, Tim. The poem was obviously one she connected with whereas I did not. It’s one poem in the whole book that didn’t work for me (two if you count ‘Giraffe’) and that’s fine. Yes, you could have added a footnote or revised the poem but you chose not to and that’s fine too. I decided to highlight the poem partly as an excuse to draw people’s attention to your essays and your general views on poetry. I don’t think it was worth making too much of a fuss about.

ReplyDeleteDebates will rage long after we’re all gone as to just how obscure a poem ought to be. And there is no right answer. Some people seem to be comfortable with a vague comprehension of a poem, others, like me, not so much. So I steer away from that kind of poetry just as I avoid music that doesn’t do it for me. There is more than enough music and poetry out there to keep me entertained for the rest of my life. As I’ve said before I do seem to have a greater tolerance for difficult art and music than I do for poetry.

Puzzles are all fine and well as long as all the clues are there. I object to crime writers who bring in a piece of evidence in the drawing room that the readers have not been privy to. I don’t think that’s fair. The reader should have all the clues, the red herrings, the MacGuffins, available to him so that he can go back and say, “Damn it! I should have got it on page 73,” and there’s a delight in knowing you’ve been hoodwinked. The first poem in your book does that. There are clues before the end of the poem’s big reveal and there will be those readers who work it out before the last line and feel smug because they did. But, as I’ve said, what I feel is wrong with ‘Iron Birds’ is that the vital clue is missing and if one has never heard of cargo cults one is at a distinct disadvantage. Now, the real test is: Can the poem still work without that information? An example: Film by Samuel Beckett takes its inspiration from the 18th century Idealist Irish philosopher George Berkeley. Knowing that is a help in understanding the film but it is not essential.

If a poem is a machine does it need all its parts to work? No. I had a mate who fixed my TV for me back in the 1980s and, once he had finished, he handed me a few components and said, “Don’t leave it unattended.” But it still showed programmes, changed channels and had a volume that worked so I never worried what the parts he removed were supposed to do. I suppose they did something. Is a knowledge of cargo cults a key element in ‘Iron Birds’? I personally think so. I don’t think it works properly without it. But I don’t think that ‘cargo cults’ is the answer to the poem. It’s not a puzzle to be solved, not in that way.

Like Dave, my interest has been provoked by commentary and sample here. My only quibble with your otherwise informative and incisive post is its provision of not one but two ear-worms. Donovan I can tolerate, Brotherhood of Man not.

ReplyDeleteBut what a pleasing jolt at the end of it all to see my interview offered as further reading.

I did apologise in the post, Dick but it was the first example that jumped to my mind and it does work in exactly the same way as the poem, it’s not until the very end we know we’ve been had. The Donovan song I can’t place but I was never a huge fan despite the fact he was born in Maryhill which is only a short car ride from where I live. I know his famous singles and that’s it.

ReplyDeleteGlad your link popped up at the bottom. I have to say I do like those little LinkWithin icons. I don’t know how much they’ve encouraged readers to check my other posts but as soon as I saw them on some other blog I thought: They’re for me.

Excellent review and this looks like the kind of 'difficult poetry' that it's worth reading, it seems as though there is a lot of substance to it. (Iron Birds certainly speaks to me already having read the notes as well.)

ReplyDeleteThanks by the way for your comment 'the future is the future' on my Over Forty Shades blog. While to a certain extent I entirely agree, I think that futures that are radically different are worth writing about partly because hopefully they make interesting readng and partly because they can deal with issues in an enlightening and thought provoking way. Not that I'm wanting there to make great claims for my own writing...

I agree, Dave. The same goes for poems that overuse metaphors. It amazes me that Dick Jones can write the kind of poems he does and make them work. Few could.

ReplyDeleteAnd, Crafty Green Poet, actually most of the poetry in this collection isn’t terribly difficult although it’s all layered and so I have no doubt that superficial me missed a lot of it. As far as the comment on your blog goes, you’re welcome. I’d comment more but I just don’t have the time. In fact today I’ve just skimmed about thirty blogs and only left two or three to read later because I simply don’t have the time.

The point I was trying to make about novels set in the future is really to make sure that they’re grounded in the present. I’ve just finished reading a collection of short stories and two of them were set after some kind of apocalypse and my favourite was actually quite a light-hearted, continental take on the old British TV series, Survivors: no rape gangs or cannibals or road warriors, just the last of humanity sitting around, fishing, drinking wine and enjoying good conversation. I have no doubt that things would have been horrible in the cities but that’s what was so nice about this setting. A bit different.