The obvious way in which ideas imprison us is where people try to impose their own ideas on us. The word ‘idea’ is a hard one to pin down. A convenient synonym for it would be ‘thought’ – ‘I’ve had an idea’ and ‘I’ve had a thought’ being acceptable alternatives to each other. I see an idea more as a series of thoughts that reach a conclusion, something like an equation. The difference is that the steps don’t necessarily need to be logical and the answer doesn’t have to make sense. An idea is like a theory, something that needs testing, whereas an ideal is more like an axiom, a general statement accepted without proof. Some ideals can be proved and so are more akin to theorems.

The earth is flat. That was a neat idea someone once had and it gained some popularity especially when some smart-alec pointed out that the Bible said that God dwelt about the “circle” of the Earth. Ah ha! A circle is flat ergo the Earth is flat. Er, no. The Hebrew word, chûgh, can also be rendered as "sphere" apparently. In The American Pageant Thomas Bailey asserts that "The superstitious sailors [of Columbus' crew] ... grew increasingly mutinous ... because they were fearful of sailing over the edge of the world"; however, no known historical account substantiates this. His proposition is highly unlikely because, sailors were probably among the first to notice the curvature of Earth from everyday observations, for example seeing how mountains vanish below the horizon on sailing far from shore. The crew of the Santa María’s main concern would more likely have been whether or not they would run out of

There have been plenty of good ideas. The wheel was a pretty good idea and it’s been the fulcrum of thousands of other good ideas like roller skates, bikes and go-carts.

An idea is like a route. There are plenty of ways to get from A to B. Most people opt for the direct route these days but the scenic route has a lot going for it. And then there’s the route avoiding low bridges. You can drive, cycle, skate or walk, fly if it’s far enough away, or get someone to give you a piggyback. All these ideas have something going for them. And some may be ideal: they may suit the traveller’s needs to perfection.

People have ideas about writing: stories should have beginnings, middles and endings; poems need to rhyme and an actor really oughtn’t address the audience directly. Ideas are not rules. Yet many people think that the natural progression from idea is to rule. In some cases it is. Newton had an idea that apples fell to a ground because they were obeying an unknown rule so he worked it out. And now everyone accepts that apples, saucepans and little old ladies career earthward at a rate of 32.2 feet per second per second, the law of gravity says so. So where do laws fit into the scheme of things?

Hypothesis

Tentative explanation

Theory

Verifiable explanation

Theorem

Demonstrable explanation

Law

Definite explanation

There is a popular school of thought that purports that laws are meant to be broken. That is why someone came up with the idea of escape velocity and worked out an equation to take it right through to a theorem. (Actually it’s a speed and not a velocity, so there.)

Once an object has achieved escape velocity it hasn’t actually broken the laws of gravity; it’s circumvented them. Laws only apply under certain conditions. They have limits. If Newton’s apples had decided to head up instead of down at 25,000 mph he might never have discovered gravity at all.

What’s the difference between a rule and a law? Like ‘thought’ and ‘idea’ we think we can interchange them at will. Here are some rules that aren’t laws:

1. To join two independent clauses, use a comma followed by a conjunction, a semicolon alone, or a semicolon followed by a sentence modifier.

2. Use commas to bracket non-restrictive phrases, which are not essential to the sentence's meaning.

3. Do not use commas to bracket phrases that are essential to a sentence's meaning.

4. When beginning a sentence with an introductory phrase or an introductory (dependent) clause, include a comma.

5. To indicate possession, end a singular noun with an apostrophe followed by an "s". Otherwise, the noun's form seems plural.

6. Use proper punctuation to integrate a quotation into a sentence. If the introductory material is an independent clause, add the quotation after a colon. If the introductory material ends in "thinks," "saying," or some other verb indicating expression, use a comma.

7. Make the subject and verb agree with each other, not with a word that comes between them.

8. Be sure that a pronoun, a participial phrase, or an appositive refers clearly to the proper subject.

9. Use parallel construction to make a strong point and create a smooth flow.

10. Use the active voice unless you specifically need to use the passive.

11. Omit unnecessary words.

On the whole they’re not very good rules, are they? Because they’re not clear, there’s wiggle-room. Who decides whether a word is unnecessary or not? When exactly might one need to use a passive voice?

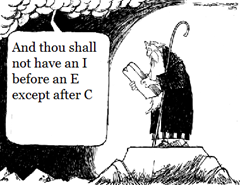

The problem with English is that it’s not Maths. No sooner have you made up a rule like

than you have to start listing exceptions:

beige, caffeine, casein, cleidoic, codeine, conscience, deify, deity, deil (Scots, devil), deign, disseize, dreidel, eider, eight, either, feign, feint, feisty, foreign, forfeit, freight, geisha, gleisation, gneiss, greige, greisen, heifer, heigh-ho, height, heinous, heir, heist, inveigle, keister (slang, buttocks), leisure, leitmotiv, monteith, neigh, neighbour, neither, obeisance, peignoir, prescient, rein, science, seiche, seidel, seine, seismic, seize, sheik, sheila (Australian slang for "girl", not capitalized), society, sovereign, specie, species, surfeit, teiid, veil, vein, weight, weir, weird

Because of this people have suggested a few qualifications to this particular rule:

- The rule only applies to digraphs, so words like "deity" and "science" don't count.

- The rule "i before e except after c" should be extended to include "except when said 'ay' as in 'neighbour' and 'weigh'".

- The rule only applies to digraphs that have the /i:/ ('ee') pronunciation, as in 'piece'. (Note the conflict between this and the previous item.)

- The rule doesn't apply to words that are recent imports from foreign languages, such as "gneiss", "dreidel", and "enceinte".

- The rule doesn't apply to the large number of plurals of words ending in "cy" ("fallacies", "frequencies", "vacancies", ... ) because in the UK – in traditional RP – "cies" is pronounced with the "i" of "pin", even though it is pronounced with the "ee" of "feed" by most World-English speakers and by younger UK speakers.

which is all well and good but in all seriousness who is going to remember them?

So, we start to see the problem with English. If its rules for spelling and grammar are so shaky then once we move onto forms of written and spoken English it’s pretty obvious that we’re going to encounter similar obstacles. For example: what is a poem? Okay, okay, let’s make life easier: what is a sonnet? A sonnet is a type of poem with fourteen lines and a prescribed rhyme scheme. Here are a few examples:

| abab cdcd efef gg | |

| abab abab or abba abba + cde cde or cdc cdc | |

| abab abab cd cd cd | |

| abab bcbc cdcd ee | |

| aBaB ccDD eFFe GG (uppercase masculine rhymes, lowercase feminine) |

Then of course there was Francesco Berni's caudate sonnet which has fourteen lines plus a coda and Gerard Manley Hopkins' curtal sonnet which somehow managed to limp home with only 10½ lines; it consists of precisely ¾ of the structure of a Petrarchan sonnet shrunk proportionally.

England Expects...

dead flowers

soldiers

opium words

incensed like lambs

they to war go

acting out

pubic farm girls

innate tensions

clinging corpses

hold guns like dolls

dirty bandages

bloody bits of men

bone white cross

wreath

forever

2 May 1977

It has its flaws – hell, I was only seventeen when I wrote it – but the idea behind it is sound, to mix up images, girls playing with dolls that have missing limbs and men being blown apart in a war. There are times when things need to be stated explicitly but not always. The important thing about this poem is that I decided beforehand what the rules were going to be before I wrote it. The problem is that I never wrote them down so I couldn’t tell you what they were. Or why. (Oh, look, a sentence without a noun or a verb.) Here’s one where I do remember the rules:

True Love II

My father had a heart transplant.

Years ago, before I was born,

doctors took

out his broken heart

and gave him a machine instead.

The strange thing about this machine

was it was

powered by sadness.

Of course he was always just "Dad",

but, when I discovered the truth,

at first I

hated the sadness

then I became thankful for it

because as long as I could see

him be sad

he would be with me.

And so I made it my job to

make him the saddest dad in the

whole wide world.

What else could I do?

21 July 2003

The poem consists of five stanzas each containing four lines of 8-8-3-5 syllables. The first lines of sentences are flush left and the rest indented. This structure wasn’t one I decided on a whim. It doesn’t have a name. I will probably never use it again. If I do it will be because the poem falls naturally into that shape. Of course it started out with each line containing eight syllables. The reason for splitting the final line was to give ‘What else could I do?’ its own line to provide emphasis. Having done that with one stanza my “rule” says I have to do it with every other one.

I don’t think anyone reading modern poetry needs to have it pointed out that you don’t stop reading at the end of a line. The breaks in the lines for me primarily are there to emphasise the underlining shape of the piece. The punctuation is there to tell you when to pause and breathe. I don’t format every poem this way but I find this helpful where the sentences are a bit on the long side, as a visual aid.

There are no universal rules for formatting poetry. A part of me wishes there were because I look at some poems and wonder why on earth the poet has arranged the piece the way he has. No doubt, like me, he thought it was a good idea at the time and it made sense to him at the time but what about thirty-three years later as in the case of ‘England Expects...’? All we have is what’s left on the paper, no memories, no working notes, no nothing.

Here’s a poem by Michael Spring from his collection, Blue Crow:

stone

I have held on

to your passport. No, it doesn’t

give me a sense you’re still

alive -- inside the passport

your face is more ghost

than flesh

this is your stone

face, you had said. It’s like this

with all photos of you --

picture after picture

a stone wall

but I’m not stopped --

memories of you move me --

I know what was behind --

your face --

I hold the passport, travelling

through stone

I picked this poem pretty much at random out of a pile of poetry books I happen to have sitting beside me. He won the 2004 Robert Graves Award so I have no doubt that he can write a decent poem or two. The thing I don’t get about this piece is why he’s chosen to use the formatting he has. Is there an underlying logic at work here that I can’t see or has he just arranged the piece this way because it felt right?

I tend to come down a bit hard on ‘it felt right’ which I concede is a little narrow-minded of me but I can’t help it. This is because to a certain extent I’m imprisoned by my idea of what good poetry should be. I wouldn’t say I was close-minded, that’s going too far, but I’m not as open-minded as I’d like to me. Those who read this blog on a regular basis will realise that I regularly expose myself to all kinds of writing hoping that, as if by osmosis, I start to get where these other writers are coming from. Mostly I don’t.

I don’t know about you but once I have an idea in my head it can be hard to shake it. I do recognise that I’ve an unfortunately blinkered view of poetry. You could say that I’ve no one to blame but myself but I don’t think that’s strictly true. I’ve read a lot over the years but there’s a lot of stuff I don’t understand. What I do understand it that a poem is a form for containing poetry. Poetry is something else. Prose can contain poetry.

I know there are plenty of people who can move between instruments from all kinds of families with ease – and I hate them – but I’m very much a one-trick pony and have learned to live with it. Poetically I can manage two or three but I’m only really good at the one. Perhaps one day the voice of the poet inside me will break.

The Weakest Link

A long time ago

someone bound me

to the pillar of reason.

It might even have been me:

I can't remember now.

But don't think me tamed

after all these years.

When was the last time

you looked at my eyes ?

When was the last time

you really looked

at my eyes ?

Even the finest chains rust in time.

6 August 1989

I can't get away from the idea that the idea of having an idea is something which you understand - or think you understand - perfectly well. You know what you mean by it, and can dish out examples until the cows come home, but every definition you come up with falls short. My dictionary doesn't get much beyond saying it's an opinion or a suggestion! To me it's closely associated with the Eureka! moment. Thought is obviously a close match.

ReplyDeleteI agree with your thoughts on Blue Crow. The formatting (and lineation particularly)make no sense to me.

I can only think that the poem 'stone' is supposed to look like a face chiselled out of rock, and that we're supposed to be seeing it in profile.

ReplyDeleteIt's a good poem though.

gwilym

This is something that I’ve become increasingly conscious of over the years, Dave, the fact that we all make assumptions when it comes to meaning. I mean, seriously, who out there doesn’t have an idea what the word ‘idea’ means? And yet how did we arrive at our understanding of that word? Someone explained it to us no doubt and then over the years we saw it used and gradually developed a rounded out view of the word. But what if everyone has simply copied what’s gone before them and they got it wrong somewhere along the line? A bit like Chinese Whispers.

ReplyDeleteAnd, Gwilym - nope, can’t see it. Never even thought to look for it.

This is an issue I’ve had for a very long time. I’m not being difficult when I raise it. I genuinely want to understand why other poets write the way they do. How else am I going to grow as a poet? I have no problem with the words in ‘stone’ but I don’t get its structure. Basically I ignore it. It doesn’t take away from the poem but then neither does it add anything. Not for me. That’s why I’m keen to hear if anyone out there can see what I’m clearly missing.

I think if you it you have to have a reason. I do it infrequently. In fact, hardly ever. I did it in a poem about Simon Rattle conducting a symphony - and it worked. But, like you I don't know why so many do it when it's obviously not part of the poem's message. I know that Dylan Thomas did it to see if he could do it (it was in the days before computers and so not so easy). He did a series of poems in strange shapes like diamonds and Xs and so on. But he did tell Vernon Watkins, in a ltter I believe, that he was only experimenting. He soon dropped his experiments and went back to normal. I have a 550pp bokk by the new American laureate in front of me. I've just reviewed it at PiR. He doesn't do it either. So, basically I'm with you. Don't do unless you have to. But if you do there better be a bloody good reason.

ReplyDeleteOne of the issues I have, Gwilym, is that a lot of people get offended when I ask them to explain why they’ve made the choices they have. As if they’re beyond questioning. I make a point of sharing the whys and hows of my craft. But I can only talk about why I do things and sometimes so many years have passed since I wrote the poems that I have no idea what I was aiming for. What I do know is that I’d always had a reason for doing something. In some cases I have been trying something new just for the heck of it but that’s rare.

ReplyDeleteI did think about trying to track down Spring to ask him but I wasn’t trying to make an example of him. In all seriousness I simply picked up the first couple of books that came to hand and flicked through them. The bottom line is that a reader almost never has access to the author. They have the book in their hands and that’s it; they have to sink or swim based purely on what’s there.

My use of line breaks these days is primarily to underline structure. They don’t add anything as far as meaning goes or very little. I don’t think what I do is perfect and I’ve been thinking of adding in spaces in the lines to indicate missing beats but I’m not sure yet. If I do it then I’d want it to add to the poem in some way but the most important thing is that the line breaks don’t take away from the piece.

Most people don't try very hard to get out of the mental boxes they find themselves stuck inside. I give you a lot of credit for always wanting to get outside the box, even if you yourself don't believe you succeed very often. At least you keep trying. Most don't bother.

ReplyDeleteWe're very different in our approach, of course. I'm very much of the "it felt right" to arrange a poem that way school, as you know. I don't plan, and I don't often go back and analyze whatever plan had emerged. "stone" looks just fine to me. It reminds me of a pared-down Theodore Roethke, or Robert Duncan, or some of Jean Valentine.

Sometimes the indentations in such a poem are sub-thoughts, sub-paragraphs even, the digressions that take the scenic route to get from A to B. Whitman often wrote using levels of indentation in his list-poems, so you could tell by which level you're on which is a sub-clause and which is the main argument.

Not every poet can, or even wants to, talk about the whys and hows of their craft. There's a certain fear that over-discussing the mechanics of craft will kill the inspiration. Which I think for some poets is legitimate. For others, poets who write mostly from the head anyway, talking about craft is fine, because that's mostly what their poetry is about. When I wrote my poem "a shaman's critique of pure poetry" I was making the point—using both syntax and arrangement on the page as a way of demonstrating the point not just talking ABOUT it—that poetry needs to be somatic, embodied, physical, not just mental. If you don't think the arrangement on the page matters, then why not just write prose? (With some poets, frankly, it's hard to tell, anyway.) The great Chicago architect Louis Sullivan coined the phrase, "Form follows function." For me, the form of the poem closely follows the function of the poem, and while I might experiment with form I don't ever give it primary value when writing. Form is the scaffolding; it has no meaning separable from its supportive position.

Speaking of mental boxes, one I find most poets get stuck in sooner or later is the idea that poetry needs to be more like prose. The questions about arrangement on the page, frankly, fall into that category.

ReplyDeleteThere's a problem when a poet grows up on prose, is taught the rules of prose (and or prosody), but only reads poetry. Our training is often towards prose-based ideas about literature. It even goes to the absurd length of expecting poets to also be able to write a novel, or vice versa. Literature is literature, the argument goes, and you can say the same things in any form. But if you can say the same things in any form, why bother choosing one form over another? Which is the better container for what you want to say?

Nearly all poetry is elaborate saddlery that never touched a real horse. When you find a poet that gives you the horse, you grab on for as long as the ride lasts. Most poetry doesn't give you the ride. You read it once, smile or shrug, and never come back to it.

Time after time I witness poets being unable to comprehend the idea that the reason they think poetry needs to follow the rules of prose grammar and syntax (like using full sentences and punctuation, for example) is ONLY because all the grammar rules they were taught in grade school were prose-based rules. Nobody teaches prosody, everybody learns prose.

The whole fashion for "plain language" in poetry is a prose bias. Thank the gods for exemplars like Dylan Thomas and Hopkins who demonstrated that complexity can also be musical, and beautiful. Frankly most poems I see these days is just prose broken up into lines; what it lacks is the poetry.

At one point does there stop being a point to a form, and it just becomes habitual. I see plenty of poets write in more or less the same form all the time. It's habitual for them. (It's excusable perhaps with haiku and its related forms.) The same number of lines; always a couplet, almost never a big block; the same length of thought. It begins to have a certain preciousness after awhile.

ReplyDeleteif you really want to break out of the ideas which imprison you, you can't do it by thinking about it. Albert Einstein himself once quipped: "We can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them." That's as true for creativity as it is for politics.

To break out of the ideas which imprison you, you have to do it by letting in the wildness, the archetypal opposites. If you're mostly an Apollonian poet, which most are these days, you have to get over your fear of the Dionysian, and let it in. Poetry is inherently a Dionysian art, and for the past several decades it's felt very straightjacketed by the intellectual, Apollonian ideas about poetry that have become dominant.

I can fully understand a poet not wanting to talk about a work in progress, Art, but once it’s finished and published – set in stone if you will – then where’s the harm? You raise a lot of valid points about the state of poetry today but it’s easy to trace the root of the problem. You said it yourself, no one teaches prosody. I was never taught how to write a poem. I was barely taught how to read a poem. Is it any wonder than I write the way I do? I’ve had to pick up what I could where I could. When I left school I used to get poetry books out of the library but they were just anthologies. Where were all the books on How to Write a Poem in 10 easy Lessons?

ReplyDeleteNow what do I have to pass onto those younger poets I meet? Not nearly as much as I should. And that bothers me. There is the argument that I’ve never had to unlearn things in order to discover my own voice and that is a plus but I think my own voice would have broken through regardless.

There’s room for all kinds of approaches to poetry in this world and I’m not trying to set down rules for anyone other than myself. But I do think you need rules. When Schoenberg developed the twelve-tone system he also set down his set of rules for implementing it. To the best of my knowledge no one has come up with an alternate system. When I first discovered it I wrote a set of five pieces using tone rows but I’ve no idea if I did it right. I took what I read in books and did what made sense to me. Granted the books I was using were very basic and I’ve since seen others which would have been much more of a help but I don’t see that happening with poetry. The How to books on poetry all concentrate on old-fashioned forms because they have rules and it’s easy to teach rules. Most modern poets haven’t torn up the rule book – they never knew there was one.

I don’t think it strange that as a person who’d only written poetry for twenty years I sat down one day and wrote two novels nor did I find it strange about five years later when I sat down and wrote a play. Could I not have expressed the ideas I had in poetry? Not in the kind of poetry I’m capable of writing. Williams wrote a poem five books long but I haven’t written a poem longer than a page since I was a teenager.

The reason I like poems punctuated in the same way as prose is that everyone knows the rules. They know to pause when they get to a comma and to stop when they get to a period. I hate the poetry of Cummings not because it’s bad poetry - because it’s anything but - but because I don’t know what set of rules he’s using. I would have no problem learning them. I would have no problem with any author of prose or poetry writing in a completely new system as long as they set out the rules before I started to read their work. Is that not a reasonable thing to ask? Why should I have to work it out for myself only to find out that there were no rules, they just did what they did because it felt right at the time? Or that the rules change from poem to poem.

The written word is encoding. We need to decode. You can’t break a code until you work out the rules.

Jim, there's another aspect to this that we haven't come to yet and that is the ethics of the thing. In the book of which I spoke, it's 550pp by Merwin, each poem diectly follows the next, only a 2 or 3 line gap, there's no trick as with Heaney of a 4 line poem and then 90% of a blank page and then another 4 line poemand so on, and perhaps a 14 line poem thrown in now and again. And so these poems that you are talking about that very often are little more than so-called breathing gaps in unimaginative text might they not be pulling the wool over our eyes a little bit? If I can fill a page of text with 20 words scattered about why should I go to the trouble of writing 40 lines of poetry? And why should anyone go to the expense of buying it?

ReplyDeletebest,

gwilym

gwilym, your objections to white space and formatting are an accountant's objections, not a poet's. They don't stack up for precisely the reasons that Apollinaire was moved to write a poem about rain in lines across the page that looked like falling rain. If you're going to argue for only full pages being worth the reading, then I suggest you steer clear of haiku anthologies. Besides, those are often the publisher's choices, not always the poet's; some Collected Poems therefore have more than one short poem per page.

ReplyDeleteAs for the length of the poem itself, that's another false argument. Issa could get more into 17 syllables of haiku than most contemporary poets can get into a full page, including Heaney at his slackest (and I like Heaney, so that's not a dismissal, just an observation that even good poets write crap at times). Poetry has always been about compression, and the details, and tight focus, and heightened speech—which sometimes calls for shorter forms.

If a poem doesn't pull me into an experience then it doesn't matter how long it is, or how many pages it takes up. There is no inherent advantage to a sonnet over a haiku, just because it takes up more of the page. That's a ridiculous way to judge a poem's worth.

Jim, there are indeed many ways to do poetry in this world. But your underlying assumption, and it's an incorrect one I believe, is that every one of those ways of making poetry has a rule-set. Or that each rule-set can be explained. I see you clinging to rule-sets as very much an idea that imprisons you, to use your own analogies. I don't claim that there are no rule-sets; for some things there are very clear ones; but for others there is no usefulness is knowing the rules, because they don't serve us well.

ReplyDeleteThat was the point of the Einstein quote. If you keep looking for rule-sets, you'll certainly find them, but they won't help you learn how to write a poem without using rule-sets.

Another assumption you make which I question is that poems are ever finished. I think it was Paul Valery who once said, "A poem is never finished, only abandoned." That rings true to my own experience. Explaining a finished poem might not be something that can be done, if the poem isn't really finished.

And the assumption underlying that is that poets ought to have to explain anything. There's no rule that I'm aware of that requires me to teach younger poets how to write poems. In fact, when asked I usually tell to go read lots of good poetry, and learn by reading, imitating, reading more, then writing. I see no reason for poets, whether or not I like their work, to have to explain or justify themselves, or explain their poems. Craft lessons all too often degrade into defensive justifications; I don't argue with you there. But I don't see why it's a problem. We're not talking engineering here, after all.

This is what I meant by letting in the wildness: I mean, abandon the idea that everything has to have rules, or should. Just cut loose. (Of course if one wishes to portray cutting loose as another rule-set, that's fine, as long as one still cuts loose.)

Actually there are several post-Schoenberg rule-sets for composition. Yes, they're all based on the same basic principals, but there's a reason Webern sounds so different than Babbitt.

ReplyDeleteAnd furthermore, Schoenmberg was not innovating: his work was the end of Romantic chromaticism, not the beginning of what came after. Actually his most innovative work was the sprechstimme period, not the serial period. He was still an incredible tight-ass about following his rules, and his compositions are all Romantic in essence, not truly Modern. He was the end of a progression, not the beginning of one.

I would have no problem with any author of prose or poetry writing in a completely new system as long as they set out the rules before I started to read their work. Is that not a reasonable thing to ask? Why should I have to work it out for myself only to find out that there were no rules, they just did what they did because it felt right at the time? Or that the rules change from poem to poem.

ReplyDeleteThe fact that this really seems to bother you so much (assuming we're not all being rhetorical for the sake of discussion here) tells me more about you as a reader than about you read. :) Again, I think you're stuck on the systems and not on the content.

Actually, I don't think any writer is required to do any such explanation. Sometimes the fun is figuring out that there are no rules, or if there are just what they are. I read Joyce's Ulysses before I read any of the "explanations" of it, and I had a fine time reading it, thanks. Ditto Beckett. Any reader can find something in a great work of writing, based in part on their experience and their previous reading.

Requiring the writer to have explanatory texts, or gods forbid footnotes, is the mark of a poem or play that cannot stand on its own two feet, on its own merit. Intellectual understanding of every nuance is not necessary for the pleasure of reading. Requiring the writer to have written a manifesto stating their intentions clearly is even worse. Where's the pleasure of discovery on the reader's part? Where's the joy of flying out in the open air, free as the wind, not knowing where you'll land? In short, where's the adventure in reading? And if there's no adventure, no joy in discovery, then school textbooks have the same literary merit as great poems; which is to say, none.

I'm going to be lazy and say I agree with everything Art said seeing how he said it so well :)

ReplyDeleteArt, they may be an accountants objections but that doesn't make them invalid. I could go to the extreme and say here's a poetry book with one word on each page, or here's a poetry book with one letter on each page or here's a poetry book with nothing in it - only full of blank pages. What I'm getting at is where to draw the line if indeed a line has to be drawn. And the line will be drawn by the reader who the purchase the books and not by the poet or his publisher. Poetry, if it is to survive, has to provide value for money as well as all the other things. Gimmicks and tricks will of course come and go according to the fashion.

ReplyDeleteBut I'm not saying for one moment that all poetry has to start hard to the left margin (or the right margin in the case of Arabic etc.) but it has been proven over the centuries that that is the best layout for the reader, and for the poet who wishes to get his message across.

ReplyDeleteGwilym, I have to go with Art here. To my mind a poem is a standalone piece of work. I rarely write more than one a day and it gets presented to my wife on a single sheet of A4 paper irrespective of its size. I take my time arranging it on the page and I also choose a font to go with the piece. In my own collection I never considered for a second trying to cram in as many poems as possible.

ReplyDeleteArt, no, I don’t assume that every poet has a set of rules. I know full well that most just dump the words on the page whatever way they come out and never give them a second thought: if it looks like a poem then it must be a poem. What I’d like to see is some of these poems asking the questions: Why do I do the things I do the way I do them? Is there a better way to write a poem?

As to whether a poem is finished or abandoned it’s just semantics. There comes a time when a poet stops working on a piece and tries to get it published so it’s clearly finished enough. If he goes back and reworks it then fine – Stravinsky pottered around with The Rite of Spring all his life but does that mean that what they heard on that first night wasn’t finished? Hell, it still gets recorded in that form.

As for whether older poets should share what they know, again there is no rule that says we should. Indeed I could easily take the attitude that I struggled and so everyone else should. But I don’t. No matter what kind of poetry you write there are techniques. You can’t deny that. In fact I imagine you think a lot of the time that I need to unfasten my top button and you’d be right. That can also be taught.

I take your point about Schoenberg but at the end of the day he was the one who put down the twelve-tone system on paper even if he was quite academic about it and left it to others to make the most of it.

As regards your last point, up a point I agree but there’s a fine line between giving your reader something to get his teeth into and making life difficult for him. Maybe I’m a lazy reader but when I see a poem sprawled all over the page I don’t think, Hm, I wonder what I’m supposed to get from this? No, I think, Christ! Look at that mess. I’m used to reading music according to the European tradition. I don’t need a glossary explaining all the terms and symbols. But I’ve just found a snippet of Hans-Christoph Steiner's score for Solitude online and it’s very pretty but meaningless to me. No doubt the piece came with notes.

I’m not saying that every book of poetry should come with a similar set of decoding/interpreting instructions but there are some where a few notes would not go amiss. Case in point Beckett’s late prose. I have read them and I’ve read about them and nowhere have I found the kind of answer I need. I persist only because it’s Beckett. Had All Strange Away or How it Is been written by someone unknown to me I’d probably never have finished reading them.

The bottom line is that you ask why and I ask why not? All I can say from a personal point of view is that I’m very grateful for those authors who’ve got off their high horses and sat down with me for a few minutes and said, “Look, this is what I’ve done, this is how I did it, this why I did it and this is what I expect you to do with it.”

And, lastly, Marion, since we’re being lazy – thank you.

Jim, I hope I haven't given the impressions that poems have to be "crammed on the page" because that's the worst thing that could happen to them. What I'm getting at is something like in this Bukowski book I have beside me. It goes like this: the poem IRON finishes third of the way down the page like this:

ReplyDeleteold habits often die

as slowly

as do old men.

EXTRATERRESTRIAL VISITOR

it was a hot afternoon in July.

her daughter was at the swimming

pool.

her son was at the roller rink

...

(and then ET VISITOR a third way down the next page where SMALL TALK starts:

SMALL TALK

I left the barstool to go

to the men's room

___________

I can't see that as cramming. OK maybe not standalone either. But it's OK. I like it. I feel I'm getting more Buck for my pound and what's wrong with that in today's cut-throat publishing world.

It did come across a bit like that, Gwilym, but at the end of the day it’s personal preference. Some people are content with art in books, other feel you need to go to art galleries. I think presentation is important which is why I’m not opposed to a bit of white space. I could live with two small poems on a page if they were well-spaced.

ReplyDeleteI shall avoid entering the smoke-filled room that accommodates the debate following this excellent post.

ReplyDeleteInstead, I'll just state that I really enjoyed the three poems you used as illustration, including the piece of juvenilia, which demonstrates a confident voice even so early. One day, maybe after I have taken sufficient alcohol, I shall share some of my premature poetic effusions. At least I can laugh about them now!

The whole rules of language thing is a fairly recent development - it seems to parallel the rise in literary criticism and laterly lit theory; with the rules comes the notion of language as some sort of science, and now the study of it utilises its own meta language: a linguistics of linguistics. But surely the whole point of having rules is that they only exist by virtue that they have an alternative binary. Viz, what are rules for if not to break?

ReplyDeleteAs for the prose/grammar debate. I use punctuation in poetry because I like the syntax; I like to play within a slef-constructed set of constraints. Conversely, I use very little punctuation for dialogue in novels. There's a difference, I think, between speech and the written word. Ah, I hear you say, but poetry is meant to be spoken, written to be heard. And yes. But poetry, for me, is about form - even if that comes through the attempt at an omittance of form. Dialogue speech portrays the haphazard, un-thought-out. But I'd never limit myself to one idea, set myself in stone with one set of concrete thoughts.

Ah, Dick, I remember the confidence I had back then. I’d breenge into anything without much thought, even a poem. You should put up one or two early pieces. I think it’s good to show younger poets that you don’t just start off writing great poetry. I look back on some poems I wrote years ago and I remember just how pleased I was with them and they’re awful. But they were an improvement on what I had been writing. And that’s the main thing.

ReplyDeleteAnd, Rachel, of course language is a science but it’s also an art; that’s where a sentence differs from an equation. There’s only one way for 2+2 to equal 4 but there are lots of ways for a chicken to cross the road. I’m not sure that it’s as simple as breaking rules. From what I can see most people have come along and rewriten the rules. If there were not rules, even loose ones, we wouldn’t be able to identify an Imagist poem or a Beat poet.

I think the expression you use – “set of constraints” – is a good one. The word ‘rules’ can get people hackles up. And you’ve obviously not read my blog long enough – I would never say, “Ah, but poetry is meant to be spoken, written to be heard.” My poetry is not written to be read aloud. Of course it can be but that’s not something I’m interested in and the visual element is an important one. If, by the way, when you say, “I use very little punctuation for dialogue in novels,” I hope you don’t mean you don’t skip out on quotes. I’ve read a few books of late with no quotes and I cannot stand them. I cannot for the life of me see what there is to be gained by omitting them.

All fair points, Jim, all fair points. As far as I'm concerned there are an almost infinite number of ways to get to Rome, and most of them no better than any other. There are the paths and methods we might individually prefer, but when we all arrive, most of that preference falls away.

ReplyDeleteIf I overstated my position it was to make the case that there ARE many roads to Rome. Yes, I know we're very different kinds of writers, you and I, and I certainly think your way produces good poems. At the same time, I've often been criticized by rule-based poets (such as neoformalists) for the fact that I don't use their rule-sets to write—even when they like the finished/abandoned result.

(BTW, I agree to a point that the distinction between finished and abandoned is semantics, at least in terms of practical results, i.e. what gets released to the public—but we're writers, so choosing the exact word matters very much indeed. And so dismissing it as a semantic distinction, well, seems off-point.)

To follow up on something that Rachel Fenton said: One of the main reasons there is so much emphasis on the rules these days, Rachel, is that craft is ALL that can be taught. You can't teach a poet what to write about, you can only teach them how to write about it to the best of their ability, using their best craft. All that any workshop or school or teaching situation can teach a writer is the mechanics of craft. They can't teach the hunger to write; you have to bring that to the room yourself.

Jim, I absolutely agree that it's a wonderful thing when a poet talks about their process, about their poetry, about how they did it. I love reading poets' essays about poetry, about translation, about what they like to read, what writers they admire. I regularly collect and read poets' books of essays, reviews, and criticism.

But short of following their recommendations to go read poets they admire, there's almost nothing I can DO with any of that. Teaching me about the WHY of a poem is always more interesting to me than the HOW of a poem, but most poets only tell us about the HOW; very few have ever spoken about the WHY. Mostly the why is just assumed, gods help us we're all addicted, it's why we're all here. LOL

Again, all that can really be taught is the craft. As much as I enjoy reading poets' talking about what they do when they write, the WHY of it is still usually elided.

People tell me I'm actually a good poetry teacher myself, and that I have honed skills at critiquing. I don't know, I never do anything but be honest and give them my best response. So who knows.

As to juvenilia, I have to agree on all counts. It is indeed instructive to see how a writer evolves, and grows, and how that deepens their writing. For my own part, I have binders and notebooks full of horribly bad adolescent self-absorbed angst-filled poetry—just like anybody else who didn't pitch it when they had the chance. Now I'm glad I saved it, because it's hilarious to go back and re-read some of that tripe, and know that I've occasionally done better. Most of it's unpublishable, but maybe it could serve as an example, as you say. That's an interesting idea for a future forum, perhaps. We could all bring our teenage crap to the table, and enjoy laughing at ourselves. LOL

ReplyDeleteWhy argue with a paradox?

ReplyDeleteThe thing about going to Rome, Art, and I’m as guilty as the next man when it comes to this, is that we tend to stick to familiar routes. I’m not saying I could write a poem in my sleep – I certainly never have – but when I do get an idea I generally deal with it in the same way with similar results, similar but never the same. There are some bands when you listen to them you feels like you’re hearing their hit single played over and over again just with different lyrics. I don’t get that feeling but, to keep with my illustration, the lead singer is always the same.

ReplyDeleteIf the whole world adhered to my philosophy of poetry I think we’d be in a mess. That doesn’t mean I shouldn’t keep doing what I’m doing because it obviously works for me. But I have no desire to badger people into following my way and I’m sorry that some poets have badgered you for your approach. That doesn’t mean I won’t criticise your poetry and I did with your latest piece. My criticisms were valid and I’m entitled to my opinion but, at the end of the day, that’s all it is. I’ve long had a person credo: I’ll not carry a donkey for anyone based, of course, of the Aesop’s fable about the two men taking a donkey to market who listen to everyone’s advice and end up carrying the donkey on a pole rather than the donkey carrying them. No matter what either of us do we’ll end up upsetting someone so why upset ourselves as well?

I would have thought that most of us at some time though had tried to answer that question: why do I write poetry? I most certainly have. And I keep getting different answers too. People are always willing to recommend their heroes but your heroes are unlikely to be my heroes nevertheless we keep fire burning hoping that someone else will connect with them the way we have. And I’m happy to look at anyone but most of the time I do I wonder what I’m supposed to be seeing. It’s like listening to Wagner’s Ring cycle – excuse me, just why is this not hell? And yet others, Stephen Fry most recently, have sung his praises. I don’t get him and I could list of all the big name poets that I don’t get too. I assure you there’s far more poetry that I can’t relate to than music. And as a poet that bothers me. But just telling me to read such-and-such isn’t going to help.

As far as critiquing goes you might notice that I do very few reviews of poetry books on my site. There’s a damn good reason for that. And when I do I’ve had to devote a disproportionate amount of time to them. I find them very hard. I’m simply not knowledgeable enough and I’m terrified that I make a fool of myself by saying that’s something’s crap when it’s actually a work of genius. My poetic taste buds are not very sensitive. No more than my literal ones. My wife likes a glass of wine of an evening and occasionally will ask me to taste one. I think they all taste exactly the same – crap. Give me a banana milk shake any day. It’s also why I’ve not written articles about for example the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets because I don’t get them and when I start to read about them I just get tired. If Christianity can be boiled down to a few aphorisms then why does a school of poetry have to make life so hard for everyone?

I’m not bored with how I write but I still want to learn, to experiment, to try new approaches. I know I’m going to be like Stravinsky when he first discovered jazz – I’ll get all excited and have a go and make a mess and probably go back to my old ways but maybe a bit of the new approach will stick and get absorbed into my style and become my style.

As for the juvenilia, yes, why didn’t we pitch it? I’ve moved house so many times and thrown out plenty of stuff that I shouldn’t have but never the poems. I don’t look at them very often but when I do I don’t always groan with embarrassment. And I can see the potential, me finding my own voice. I may post some sometime but the main problem is that the better ones are a bit on the long side. I was not always as concise as I am these days.

Rachel, because we love to argue. People have been trying to solve unsolvable problems for centuries. It’s not pointless. Much can be learned in the process. By not answering the question on the table other questions, unasked, can often be answered. I saw a documentary a wee while back in which about 80 poets were all asked the one question – What is poetry? – and the difference in the answers was amazing. Did we come to a consensus at the end? What do you think?

ReplyDeleteI loved this post Jim, even as there's not a great deal I can say about it, other than that it made me want to copy some of the points of grammar you make for future reference.

ReplyDeleteMostly I rely on my intuition with grammar. I never managed to take in the rules the nuns taught us at school.

I'm not a poet, but I've often thought I'd like to learn the rules of poetry and then I might feel free to try to write poetry and then break those rules. As it is, all I know is that something resonates for me along the way and I enjoy it, or something does not.

One other thought: the poet, Ruth Padel who ran a workshop at the conference, which I recently attended, talked about the way we like poems to come to us as readers in an open ended way, to allow for a personal response, rather than to experience the poem as if a man 'has put his hand into our pocket'.

An interesting thought.

I once knew a poet online who was a deterministic sort. He was convinced that his poem failed unless the reader got exactly the meaning he had intended, as though the poem was a form of telepathic transmission or pure communication. Some of his poems were pretty good, but he was so intolerant of ambiguity and the reader's personal response, what they bring to the poem from their own experience, that he alienated most people with his abrasive attitude. Yet he seemed to respect me, for reasons I never quite understood. I did try to explain to him why ambiguity was a good thing in poetry, how it brings resonance and layered meanings, enriches the poem and the experience of reading the poem; but he was closed to any such ideas. It had to be his single meaning intended in his transmission, or none.

ReplyDeleteThis is one of the most extreme cases of an idea imprisoning the artist I've ever run into. It ended up being self-limiting, and for all I know he writes no more poems and teaches philosophy somewhere. He was inflexible to the extreme. There wasn't much joy in the writing, more an engineering sort of approach, and a demand for perfection. It killed all the fun, all the pleasure in reading the poems. And I think in the end it killed the creativity, and the urge to write.

I've known for many years why I write, why I make music, why I make visual art. I'm lucky in that I can practice crop rotation when one of these doesn't want to be happening. I recently started writing some poems out of my recent medical hell, after not writing a thing for many, many months. Last summer and fall the poems I wrote were lyrics for the musical composition I was working on, which was premiered last winter. This past February and March I was on the road, in the mountains and by the ocean in winter, making some of the best photographs I've made so far.

The Zen answer is, "There is no why. You just do it." That's true, as well as a little glibly funny.

The psychological/spiritual answer is, If I don't make something every day, I tend to go crazy. There's always been a huge pressure in my mind and self, that comes from within, like an underground raging river, that comes out through me and must be expressed; it's this pressure that drives me creatively. I'm lazy at heart, and if I didn't feel this huge pressure bursting out, I probably wouldn't do much more than the average casual amateur. It's creative force that must be expressed. The flip side is that I can tap into almost at will, so I almost never feel blocked.

In other words, making art is as fundamental as breathing. I have to do it, or I go crazy and die, like nitrogen narcosis. And it keeps me alive. Some days it's literally kept me alive, by giving me the sole reason to bother getting through the day. So it's also "therapeutic," although that's glib psychobabble that's cheap and diminishes the reality of it too much.

And just because I want to. I like it.

Up to a point I consider myself quite lucky, Lis, in that, for one year at least (Primary 6), I had a teacher who was obsessed with grammar. I can remember no other time in my life where we spent as much time or indeed any time pulling sentences to pieces. Where I think I was unlucky is that I never truly appreciated that this was going to be and once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and so perhaps didn’t make as much of it as I should. Nowadays I doubt they do much further that explaining the definitions of a noun, verb and adjective and telling you that a sentence should start with a capital letter and end with a period – if you can be bothered.

ReplyDeleteI think if anything has come out of this post it’s the fact that poetry can have as many or as few rules as you want so it’s not a matter or learning the rules – there are no Ten Commandments of Poetry – there are as many approaches to poetry as there are breeds of dog. I mean, what is a dog? We all know what a dog is but how many of us could list the basic requirements for being classified as a dog? But we all know one when we see one.

For all my talk of rules I still believe that poetry is still something that you need a feel for to be any good at it. Techniques can enhance natural ability. It’s like a pianist. There are many technically proficient piano players out there who have no heart. Just playing all the right notes in the right order isn’t enough, nor is getting all the words in the right order or even the best words in the best order. Poetry’s not about that.

I can really relate to the guy you’re talking about there, Art, because it took me a long time to get over the fact that people weren’t getting my poetry when, as far as I was concerned, it was transparently obvious. It wasn’t till I came up with my iceberg metaphor that it started to make sense to me – they were only getting to see the tip of the poem and that’s all any of us see. It’s hard when you start off with a false premise. I was brought up to believe that my life should revolve around something called ‘the truth’ and all that has ever done is cause me upset because I’ve only ever been able to pay lip service to it. I tried to tell the truth in my poems and failed miserably. Now I have embraced the lie things work out so much better.

ReplyDeleteI’m rather jealous that you have so many outlets. I’ve dabbled in all of them over the years but little by little I started to realise that these weren’t natural modes of expression for me. Like I was saying to Lis just now about the technically proficient pianists I could and did become adept at other forms of artistic expression and they were fun to play around with but whenever I had something serious to express I always fell back on my words.

Why do I write? Because it’s part of my nature. I don’t wander round the house singing or start dancing spontaneously. There’s no real comfort in them. That doesn’t mean I’ve not cranked up the volume and tried to match Meatloaf and I have been known to dance a wee jig with the bird much to his consternation but if you caught me doing that I’d be embarrassed: words don’t embarrass me. Words bring me comfort, the act of translating how I feel into these glyphs is so pleasurable and when you do it on a keyboard it’s neat and tidy too. And I love neat and tidy. No mess to have to clear up.

I would like to exchange links with your site www.blogger.com

ReplyDeleteIs this possible?

Well Anonymous I'd be willing to think about it if you actually told me who your are.

ReplyDelete