Dear Mrs. Crosby,

I don't know who I am.

Yours sincerely,

Charles Bukowski

That opening quote probably needs some explaining. It was the response Bukowski sent to the editor of Black Sun Press following her request for a short autobiographical sketch. That was in 1946 so he would be in his mid-twenties and not well known, still to become famous, let alone infamous and perhaps even notorious before being consumed by a myth of his own making. Since his death in 1994 only the myth remains. Most myths have elements of truth in them and you would think considering that it is such a modern myth that it would be relatively easy to separate fact from fiction; all it would take would be some careful research and asking the right questions of the right people, the majority of whom are still alive. One cannot fault Howard Sounes on the first point. He spent two years talking to everyone who would talk to him and it looks like all the major players were happy to sit and converse at length.

All of what is presented as evidence, however, is anecdotal or circumstantial. It has to be. Unlike other biographers, like Neeli Cherkovski, Howard Sounes never knew Bukowski personally; he’s not even an American. To be fair he has done a sterling job in researching his subject. He devotes 44 pages to listing exactly where he got every scrap of information, those at least that aren’t explicitly referenced within the text itself. I’m not convinced that he necessarily asked the right questions or asked enough questions but if you’re like me and know nothing about Charles Bukowski then I believe this to be a solid piece of work. After finishing the biography I made a point of watching the excellent documentary Born into This which this time was the result of seven years worth of research and I have to tell you the book stands up well against the film; they actually complement each other well, although witnessing some of the things the book only describes certainly puts them into perspective; I’ll come back to you on that.

Many writers mine their lives, there’s nothing special there, but Bukowski more than most. With the exception of his last book, Pulp, all his novels comprise an extended autobiography, and Sounes wisely uses them as a template for his own biography but even they do not tell the whole story. Despite what his publisher, John Martin, has to say about him:

He hated any kind of dishonesty. He hated deceit.

Bukowski’s versions of events are not as accurate as one might imagine especially considering the unflattering, embarrassing and downright disturbing things about himself he did choose to include. He may be the protagonist of his books but he’s no one’s hero. The way Bukowski put it himself, ninety-three percent of what he wrote was accurate and seven percent was “improved upon”. The simple fact is that anyone who came in contact with him ran the risk of being fictionalised and rarely discreetly. When he was working on the book that would become Women Bukowski met Linda Lee Beighle who became the basis of the character, Sara:

‘I was basically one of his guinea pigs,’ she says, ‘one of those he researched like a curiosity.’

There is a scene in the film Factotum (based primarily on Hank’s second novel of the same name) where his alter ego, Hank Chinaski, gets fired for not pulling his weight and he fires back at his boss:

I've given you my time, which is all I have to give — it's all any man has to give.

It’s straight out of the book and has become something of a credo. A man’s time on this earth is limited. You can’t reclaim a wasted second of it. In a letter to his publisher in 1987 he talked about “coming in from the factory with your hands and your body and your mind ripped and days stolen from you...” – italics mine

This refusal to conform to the capitalist convention of an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay, also the refusal to try and ‘get on’ in life, makes Bukowski a radical American writer.

He wasn’t interested in living the so-called American dream. The irony is that once success came to him in later life he could tick all the boxes with ease.

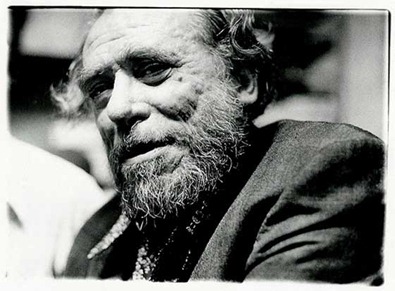

Let’s take his face. There we do get a simple explanation: as a youth he suffered for years with acne vulgaris, the worst case the doctors at the gleaming new Los Angeles County hospital had seen:

The acne was not simple spots, but a pestilence of boils ‘the size of apples’ he said. They erupted on every surface, and in every crevice, of his head and upper body: they were on his eyelids, on his nose, behind his ears and in the hair follicles on his head. They were even inside his mouth.

To see the physical effects all you have to do is take a look at a photograph of his pockmarked face like the one below taken by Hugh Candyside:

The second think that was wrong with the actors is that none had his beer gut. Dillon did bulk up to play the role but not enough. The question as to whether Bukowski was an alcoholic is addressed in the biography. Sounes provides the evidence and you can draw your own conclusions. He certainly states his own opinion unequivocally. Hank did not think he was though. Neither did his second wife, Linda Lee:

Linda Lee told [Sounes] that Bukowski was a ‘smart drunk’, making a distinction in her mind between people who are incapacitated by booze and those, like Bukowski, who drink to excess and yet still do their work. ‘Hank remained prolific ... I don’t call that alcoholism. I think alcoholism is when you drink and you can’t do anything anymore.’

Whatever name you give to it what is very clear is that alcohol was a crutch he leaned on heavily for most of his life. After falling ill with TB he did give up drink (and from all accounts with little difficulty) for many months and never returned to his binge drinking after that. I’m sure there are some who would argue that a true alcoholic wouldn’t be able to do that. I’m not going to argue the point.

What’s the first thing you think of when I mention the name ‘Oliver Reed’? I asked my wife the other day and her one word response was: “Drunk.” It was the first thing I thought too, which was why I asked. When we talked about it a bit more the visual memory that the name had triggered was his appearance on Aspel and Company in 1986 when the actor embarrassed himself in front of an audience of millions. Not the only time but clearly the most memorable. Years later when asked by Paul O’Grady about the incident, Michael Aspel had this to say:

Half of the time badly behaved guests are good telly. And you know when Oliver Reed got drunk... I mean I was delighted. People said 'Aspel was furious'. I was thrilled! You don't expect him to come on and behave like... a bank manager; if he had it would be disappointing. But we knew he was sloshed because he'd taken fifteen stops... and a couple of pints of gin and tonic. So when he lurched on I thought 'This is great!'

It’s a fact. I wonder how much screen time has been taken up over the years repeating that clip. Bukowski for the main part steered clear of chat shows, however, in 1978 he appeared on the French show Apostrophes and in the end needed to be shown off.

Wisely he stayed clear of them after that but he did not stop public readings and the word spread. Hank was a surprisingly nervous man behind all the bluster and believed he needed drink to enable him to give his readings. Often he would polish off a couple of bottles of wine while actually giving the reading and needless to say there was always someone in the audience ready to feed him lines and work him into a state. So the same kind of people went to see him read as go to wait for race car drivers to crash. Charles Bukowski was a car crash waiting to happen. Sounes describes a reading at Baudelaire’s nightclub in Santa Barbara in 1970:

[S]ubtlety was lost on this crowd. They expected an exhibition from the dirty old man: sex poems, drinking poems and scatology.

[...]

It seemed like they wanted him to insult them. ‘You disgusting creatures,’ he said obligingly. ‘You make me sick.’ They laughed like hyenas at that.

How does a man get to that stage? You probably expect him to have had a miserable childhood and you’d be right. Sadly the only three people who could talk about what when on when he was a kid growing up are all gone and we’re left with his own account, primarily in the book Ham on Rye plus what he told his friends and in interviews. The degree of Hank’s honesty is something Sounes brings into question though:

[W]hile he could be extraordinarily honest as a writer, a close examination of the facts of Bukowski’s life leads one to question whether, to make himself more picaresque for the reader, he didn’t ‘improve upon’ a great deal more of his life story than he said.

The family moved to 2122 Longwood Avenue in Los Angeles, a nicer home than the ones he had been used to, and his parents used to clean the place from top to bottom every weekend. Hank’s job was to mow the lawn, a job no doubt many of his peers would also have been tasked with. This should not have been a big job as the lawns were quite small but his father insisted that when his son had finished not “one hair” was to be sticking up, an impossible task. If he failed, which he invariably did, a beating followed in the bathroom with a razor strap:

The weekend manicuring of the lawn, and the inevitable punishments that followed for his failure to do the job properly, and for many other reasons too, became part of the routine of childhood. It was one of the reasons Bukowski came to talk so slowly – he learned to think before speaking in case he upset his father.

You would think with the kind of childhood he experienced the boy would have been perpetually running away but this was not the case. He did spend a lot of time in his bedroom – it was the only time he felt safe – and his earliest stories were inspired by the sounds of aeroplanes “droning overhead on their way to Los Angeles airport.” He stayed with them, graduated high school, and then started to look for work. When not actively engaged in that pursuit, he could be found in the Los Angeles Public Library on West 5th Street where, if any moment in his life could be described in such terms, he had an epiphany, my word, not his nor Sounes’; Bukowski likened the

Ask the Dust is written in a strikingly spare and lucid style with short paragraphs and short chapters, but it was the subject matter that was, at least initially, more interesting to Bukowski. The hero, Arturo Bandini, is a twenty-year-old would-be writer, the son of immigrant parents, who feels cut off from society. He wants to write about life and love, but has little experience of either so he goes to live in a flophouse at a place called Bunker Hill where he meets and falls in love with a beautiful girl.

He didn’t jump immediately into Bandini’s shoes, although he did make “a perfunctory attempt to live the conventional life his parents expected” but as he let them down at every opportunity it seemed it was only a matter of time before he answered the call of destiny or if not destiny exactly then at least inevitability. And so began the Barfly years, a long apprenticeship in which he only worked enough to enable him to write; at times he subsisted on one candy bar a day.

That was all a man needed: hope. It was a lack of hope that discouraged a man. I remembered my New Orleans days, living on two-five cent candy bars a day for weeks at a time in order to have leisure to write. But starvation, unfortunately, didn't improve art. It only hindered it. A man's soul was rooted in his stomach. A man could write much better after eating a porterhouse steak and drinking a pint of whiskey than he could ever write after eating a nickel candy bar. The myth of the starving artist was a hoax. – from Factotum

He did his duty when the time came and registered for the draft for World War II even writing “to his father that he was willing to serve. He passed the physical examination, but after a routine psychiatric test he was excused military service for mental reasons and classified 4-F or as he put it, ‘psycho’.” The specific reason given on his draft card was actually “extreme sensitivity” a quality that might stand a would-be writer in good stead but not one that would sit too well on the shoulders of the man he would present himself to have been at this time. Looks can be deceiving and just because Bukowski looked like a hobo didn’t make him one. Among other truths Sounes reveals

He did drink. That much is true, witnessed, documented, filmed. In fact the first word Bukowski’s daughter, Marina, learned to read was "liquor" since Hank spent so much of his leisure time in a drunken stupor. And, of course, as the years go by and he starts to live his life more and more in the public domain, facts do start to take over from fiction. But it really is, for me anyway, the earlier years in his life that are the most interesting, seeing him develop and yet in thirty-odd pages we’re already into the 1950s. It feels rushed. But did Sounes just cover the bullet points or did he say all he could reliably say? I’m not sure.

He also womanised. Or at least he would have you believe that. The fact was that the women only came with fame and, like any man, for a while he was like a kid in a candy store:

how come you’re not unlisted?

for a man of 55 who didn’t get laiduntil he was 23

and not very often until he was 50

I think I should stay listed

via Pacific Telephone

until I get as much as

the average man has had.

There are two things one should bear in mind when thinking about this biography, firstly, has the author done a good job? I would say he has having read as much as I’ve had time to from other sources. Some reviewers believe that it will stand as the definitive biography. Having not read any other I can’t say yay or nay to that but I honestly feel that 250 pages is a tad on the short side. My three biographies of Beckett fall between 600 and 850 pages and if Bukowski was such a great writer then surely more could have been said and maybe will be. That was the main objection others raised to the book. The second thing you might want to bear in mind is that although the book is well written, the subject matter may not be to everyone’s tastes. There is much unpleasantness in Bukowski’s life and there is little he shies away from discussing whether it be accidentally sodomising a male friend (apparently you had to be there) to kicking his current girlfriend during a TV interview, both under the influence of alcohol. It’s actually surprising that during his life he wasn’t more violent, considering his childhood, but he talked a good fight more often than not.

One thing that did please me about Sounes is that he quotes extensively from Bukowski’s own writing and primarily from his poetry. Until recently I didn’t even know he was a poet but the fact is he wrote more in a year – not one particular year, any year – than most of us produce in a lifetime. He was phenomenally prolific. Needless to say a lot of what he wrote was bad but that never stopped him. In the early days he never kept carbons of his work, he just sent the stuff out religiously and if it got published it got published and if it came back it came back. Probably more than any other writer he kept his eyes firmly fixed on what he was doing and took little interest in what he had done. Even when the money started trickling in he didn’t step back a gear, if anything he became almost frantic, terrified that it would dry up.

I was prepared not to like him. I expected not to like him. The thing was, like Tony Hancock (another famous drunk if you’re unaware of him), he was surprisingly well-liked and I think the unpleasantness can be blown out of proportion. When watching the documentary he broke into tears twice, once when reading an old poem about an old love he pined after for years, and once at his wedding; his vulnerability comes out when you see him at one point rushing to a window to see if ‘Cupcakes’, his then girlfriend (there were a good many), was coming in; he’s also visibly disturbed when visiting his childhood home.

I’m not fond of drunks. That’s putting it mildly. I’ve had bad experiences and that’s all I’m going to say about that. So I don’t romanticise the alcoholic writer. I do acknowledge that there are reasons behind all things and a man is not a caricature although some provide caricaturists with better material than others. Bukowski cared deeply for his daughter – I’ve read and viewed nothing that suggests he mistreated or neglected her in any way and she speaks fondly of him – he was a cat person and collected strays (not sure how much I want to read into that); his preference in music was for classical, particularly Mozart, “or ‘The Bee’ as he affectionately called Beethoven” and he would often listen to a classical radio station into the early hours of the morning.

He drank but “had little time for drugs”; he could be misogynistic but as soon as he got a woman pregnant the first thing he did was propose; to put things in perspective he was really more of a misanthrope than a misogynist; “when he was sober, Bukowski was quiet and polite, even deferential [but] when he got drunk – especially in sophisticated company, which made him uneasy – he became Bukowski the bad: mischievous, argumentative, even violent;” he gambled – he once totted up that he’d frittered away $10,000 – but he was also extraordinarily careful with his money. He is far more interesting than even he would have you believe.

I’ve not said much about Bukowski’s writing in this review. The main reason for this is that I was also sent a substantial volume of his poetry and I’ll talk about that when I review it in a wee while. The bottom line after spending the best part of a week getting to know this guy is that I’m looking forward to reading more. That I didn’t expect; not for one minute.

***

Since then he has written biographies of Bob Dylan, Bukowski (two books, there is a companion book to Locked in the Arms of a Crazy Life called Bukowski in Pictures), a history of golf from the 1950s called The Wicked Game and a cultural history of the 1970s, Seventies: The Sights, Sounds and Ideas of a Brilliant Decade. He is currently researching a book entitled Heist, about the 2006 Tonbridge Securitas robbery and a biography of Sir Paul McCartney.

As always, Jim, comprehensive, accurate and incredibly well-made piece. People tend to miss the depth in Bukowhiskey's poems. "The Genius Of The Crowd" and "To the whore who stole my poems" contain an understanding deeper than his cultural context. People also tend to forget how funny he was. How are things in Scotland? Is there a thaw yet?

ReplyDeleteJim, I don't know much about Bukowski but your review fills me with sadness for a man who clearly had enormous talent but a talent that it seems emerged out of his pain.

ReplyDeletePerhaps that's the way it is for all of us - our most creative moments come from suffering.

I suspect Bukowski was set up, first by his parents and then by the media and the world at large to perform.

I've seen this happen before: the vulnerable, shy one who takes to being rude and abusive in order to satisfy the vicarious pleasures of those in the audience who enjoy the lifting of their otherwise repressed feelings.

I should not try to make sense of a person from one short review, however well researched. But you write so well, Jim snd so evicatively it sets my heart racing.

I don't think that I am in fact commenting here on the actual man Bukowski, whom people have turned into a myth.

Yet I see something familiar here and it fills me with a sort of sadness and anger that we judge the socially unacceptable behaviors of our celebrities harshly and at the same time we expect so much from them.

Thanks for this Jim, as ever it's a terrific and powerful review and I'm pleased, however much I am saddened, to meet a version of this man through your review.

I look forward now to reading more of his poetry. Thanks.

Look forward to your piece on the poetry. McGuire is always quoting his poems, isn't he?

ReplyDeletex

I didn't know anything about this guy before I started reading (until I saw the Mickey Rourke clip and went, aah!)but I was completely engrossed the whole way through this! I'm very interested to know about his poems now and what you make of them, too.

ReplyDeleteI think both your points and Elisabeths are interesting when you touch upon his character but I'm not sure I want to try to get my head around him just yet.

Really good review. Thanks.

I agree, Paul, and I was very taken by how insightful and perceptive his poetry was. When Canongate sent me the biography to review they also included a thick (500-odd pages) collection of his poetry which I’ve reviewed separately. I think I may put that up on Thursday and we’ll just have a Bukowski week and be done with it.

ReplyDeleteElisabeth, there was a lot about Bukowski that I couldn’t relate to but there was also a sense of there-but-for-the-grace-of-God. I have never been much of a drinker – I can get drunk on wine gums – but I also recognise that I could have become one; there is a family history. I think that’s why I’ve resisted going down that route because I think it’s one I could have slipped down easily. Fortunately I cannot function under the influence. I’ve tried to write drunk and I can’t do it.

I do find my best work taps into negative emotions – no one would ever call me ‘the happy poet’ – and so I can see what a rich vein that would have been for Bukowski. And it is tempting when the work is flowing to go with that flow. I’m not saying I’ve deliberately tried to stay miserable but I’ve not always been in a rush to climb out of that misery. The question was, was Bukowski miserable? I think his childhood was, most certainly, and miserable things happened to him as an adult but I think he was more insecure than anything else. I’m sure he believed that drink was his rabbit’s foot for a long time but, as he proved in later life, he could write perfectly well sober. And his life did become more secure, both financially and emotionally, in his fifties but I expect there was always the fear that it would go away.

What I found sad was the fact that he allowed himself to be turned into a performing monkey. There was a side of him that clearly hated being in front of an audience (or even a crowd at a party) and he had to get extra-extra drunk to cope. So why, especially once he was earning enough from book sales alone, did he persist? Nothing is clear-cut.

You have had the benefit of a short review. I have had the benefit of a short biography. I think we’re both still quite disadvantaged. What I’m not sure is if we’re ever going to get a better bio. I have three biographies of Beckett and yet I still feel that so much about him I’ve observed out of the corner of my eye.

And, the-two-Rachels, I was just like you. I’ve really had my eyes opened. As I said to Paul, I’ll post the review of the poems on Thursday. As for McGuire, I’m working on an article about him just now. He’s just sent his Q+A back and one of the questions was about Bukowski so I’ll be interested to see what he has to say about him. I am in the middle of a book review so I’ve not looked but I think it’ll be a good article.

Jim, i just wish you'd read Bukowski before reading the biography. I read him before knowing anything about him; opening a crazy bright flower, indeed.

ReplyDeleteI quote him once on the inside page of my book. Don't think I've mentioned him.

Good review. What book of poetry are you reading?

I can't get over how much Bukowski reminds me of actor Jason Robards. Too bad they're both dead. Too bad they both had a drinking problem.

ReplyDeleteThe Apostrophe bit is indeed great television. It's always worth it to see the French get riled. Especially interesting was Bukowski's justification for his fondness of whores and young girls in short dresses. His slurred justification of the nature of this obsession as being a pure form of truth was recited as only a self-deceiving, highly intellectual drunk misogynist could do.

And yet Bukowski claimed he hated deception. I think the most deceitful people are those who claim they hate deception.

What a distinction to be called "dramatically ugly!" The words acne vulgaris and pustular acne have long fascinated me as have the faces that wear this badge of pain. Some famous men with acne scars: James Olmos, James Woods, Dennis Farina, Tommy Lee Jones, Laurence Fishbourne, Ray Liotta, Bill Murray and Abraham Lincoln. Why is it less honorable for women to be noted for this?

I find this man and this review extrememly interesting. Have you ever thought of writing a stage or screenplay, Jim?

I saw the quote on the inside of your collection, McGuire, which is why I asked you about him. The poetry collection is a new one: The Pleasure of the Damned: Poems, 1951 – 1993. I’ll post my review on Thursday.

ReplyDeleteAnd, Kass, yes, I see where you’re coming from here. There’s a perfect example in the poetry review where Bukowski makes up a quote to stick on the back of one of his books. As for his looks, I see that too. I’ve never known a woman with scars like that, on or off screen. Men do seem to be able to get away with it though. It gives their faces character. No one wants a woman whose face has ‘character’, not until she’s ancient and then ‘character’ is okay. It’s just the world’s double standards.

Not sure how this review piqued your interest in my experience as a playwright but since you asked, yes, I’ve written three plays in my life. You can read about them here. If you click on the links there are excerpts from two of them.

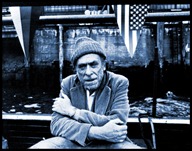

Another amazing post. That first B&W pic of Bob Lind is great. And I would have most likely answered "drunk" when asked about Oliver Reed, as well!

ReplyDeleteI know, Willow, it's a real shame when you see someone like Reed on TV. What annoys me more is the fact that people deliberately turn a camera on them. When Reed was to appear on The Tube they stuck a camera in his dressing room apparently. What is that all about?

ReplyDeleteFor a while I didn't think this was going to be for me. I couldn't get hold of the guy at all or get interested in him. Not the fault of your review, but a basic incompatibility, I was thinking. It changed a bit when you got on to his childhood. He began to come into focus, then.

ReplyDeleteI think I was much the same, Dave. I’m not very tolerant when it comes to drunks. As you can imagine Scotland is not the best place to live if you want to avoid them. I think it’s a control thing. I’m the same with drugs; the idea of not being fully in control bothers me. I’m also not a fun drunk. I need no help being depressed so why take a substance to help me down that road? But as I read more about Bukowski before he went on that bender that would last the rest of his life I couldn’t help but feel for the guy. I guess we all think we’ve had it rough until we read about someone who actually did. We all cope with our pasts in different ways. Interestingly he doesn’t seem to have drunk to forget, which is what one might imagine would motivate him to stay drunk, rather it seems he drank to be able to face the past, be it the past of his childhood or the past of last night’s blow out. Or is that me romanticising him a little? See what you think of his poetry on Thursday when I put up the second review.

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting to see how many readers reject people because of certian 'problems' they have or because they 'make no secret of themselves.' That's the thing with Bukowski, and other writers, if you don't check your pretense, you'll just feel embarassed or awkward and want to run a mile.

ReplyDeletePeople think he was some kind of wake up in the morning and start drinking kind of guy. He wasn't. People say, it's hard to tell the man from the myth, I don't think it is...he's writing 'fiction' and poetry. Beneath all the cynicism and loathing and disgust with other people, there is clearly a highly sensitive man - observant, generous, touching. He created a hardshell, a hard exterior, because so many people were just weak, watery, lovey-dovey fools. Especially, in the realm of poetry.

Amazed how many people think - o he had problems, or at least, he writes about problems and dirty things - therefore I must avoid him. How dead is that? As though life was all peaches and cream, and vanilla extract.

Thanks for this, Jim. Your usual rigorous standard is ever present.

ReplyDeleteI remember searching out anything and everything by Bukowski back in the early seventies. I think the first novel I read was Post Office, followed by Factotum; and the petry too. I still have my imported and well-thumbed copy of The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills.

But there was much I didn't know in your review, and I was particularly grateful for the scraps of video.

Makes me want to go back and read some of that stuff again.

Great article - love Bukowski. For those in Glasgow remember there is a Charles Bukowski themed bar at Charing Cross called Chinaski's which is worth a try!

ReplyDeleteI don’t think it’s just readers, McGuire, but I think readers have a real difficulty separating the writer from the written word. It can work both ways, whether you learn the sordid details first or later on. In the case of Bukowski I learned about his life before I read anything bar one poem; in the case of Larkin I was well-acquainted with his poetry and then I got to find out all the unsavoury details in his life. Personally it doesn’t bother me that much. I didn’t like what I learned about Naipaul’s treatment of his wife but I still gave his book a decent review.

ReplyDeleteThe video of Bukowski kicking his girlfriend is also not easy viewing but that didn’t stop me reading his poetry. That was him on that day and under the influence. I also saw film of him on many other days. His subject matter doesn’t offend me although some of it doesn’t interest me. I don’t like how much vomiting they insist on showing on TV but I close my eyes and then it’s gone. People throw up, it’s realistic but I wouldn’t watch anyone on the street chuck up.

Every minority should have its spokesman. Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969 for his "writing, which—in new forms for the novel and drama—in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation." Similar could be said about Bukowski.

John, I am grateful to you for posting that poem a while back because I might have backed away from the opportunity to review these books otherwise. You piqued my interest. As for the videos, do try and get a hold of Born into This - it is a very good documentary indeed.

And, Cabbage Cat, I did not know that but then I doubt if I could name half a dozen pups in the whole of Glasgow and I doubt I’ve been in more than a dozen in my life. I’m not sure a gastro-pub is my kind of venue anyway. If I was at Charing Cross there are a couple of decent curry houses I’d probably pick from to be honest. Thanks for the comment though.

Jim: As always, good work. I enjoyed the read.

ReplyDeleteWhen it comes to this fellow, I agree with Elisabeth: it's hard to see past the pain of his life, and the anger that evidently aroused in his work. I'm not sure it always had such a good effect, either, judging by (admittedly) what little of his work I've read. But I sure did enjoy your take on him.

ReplyDeleteGabe, thanks for that, appreciate the feedback.

ReplyDeleteAnd, John E, there’s no doubt that his lifestyle did have a detrimental effect on his work but he produced so much that he could afford for half of it to be crap and still produce more than most of us will ever do. There is no doubt in my mind that this guy was a writer first and foremost and that was when he was happiest, happiness being a relative term of course. I would be interested to read his prose but I’m not in any rush to do so. His poetry impressed me and I worry a little that his prose might not.

For me, the most amazing thing about Charles Bukowski was that he lived to be 73.

ReplyDeleteWhat can anybody can say about his poems that he hasn't already said about them himself? Poems like 'hell is a closed door' (on receiving rejection slips), Many of his poems are basic psychoanalysis. And perhaps unsurprisingly Hemingway (as in the poem 'zero')is seen to be his hero.

Two years before dying Bukowski published this:

'The Last Night of the Earth Poems' (400 pages in 4 chapters)The sub-headings are as follows:

1.

my wrists are rivers

my fingers are words

2.

living too long

takes more than

time

3.

the sun slants

like a golden sword

as the odds grow

shorter

4.

in the shadow of the rose

. . .

noticing the flowers talking

to you,

realizing the gigantic agony

of the terrapin,

you pray for rain like an

Indian,

slide a fresh clip into the

automatic,

turn out the lights and

wait.

. . .

I must thank Jim for bringing me back to Bukoswki whom I've neglected for a couple of years. I'll put him in my raincoat pocket for train journeys.

This is an amazing poem from Bukowski, and written two years before his death, it's prescient. It adds to my view that Bukowsi was not just a lucky drunk who won a following by being at the right place at the right time.

ReplyDeleteI doubt that he did not agonize to some extent over his writing. He probably battled as many of us do between the spontaneous and the ordained.

One of the Bukowski photographs used in your article is mine.

ReplyDeletePlease provide a credit and link or remove from your page.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/infinite_monkey/371054765/

Thanks,

Hugh Candyside

Thanks for letting me know, Hugh, credit and link added. Great photo BTW.

ReplyDeleteThanks. He was an inspiration to me, even back in 1974, when I was just a wee boy.

ReplyDeleteNice review, BTW.

It's hard to believe he was considered 4F by the Army, I doubt they understood him so simply categorized him as "crazy". Still it's a good thing he wasn't in the military, things may have turned out badly for him there, I'm afraid.

ReplyDeleteWell, Doug, I imagine in some alternate reality all people talk about are their Bukowski’s great anti-war novels. Thanks for the comment.

ReplyDelete